05/11/20

COVID-19 a ‘perfect storm’ for organ trafficking victims

By: Victor Jack

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

As global job losses mount due to the COVID-19 pandemic, desperate people are seeking new ways to make money via social media, and evidence points to a resulting deadly surge in illicit organ trafficking.

In April, Shivkumar (whose name has been changed to protect his identity) took out a loan for a power loom, confident in joining the local saree production industry.

And then the pandemic hit.

“I have no choice but to commit suicide if I do not [sell] my kidney to pay the debts,” says the 32-year-old from the Southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh.

Shivkumar hasn’t worked in six months, and the deadline for his loan of 1,600,000 rupees (US$21,700) has already passed. He also needs funds urgently to support his wife and three-year-old son.

“That group of people who were already uneducated, uninsured, unemployed are now even more desperate to take up offers which they shouldn’t take.”

Aimée Comrie, project coordinator, GLO.ACT at United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

Like millions of other workers this year, Shivkumar has been left without a steady income because of the pandemic. But his case is also emblematic of something more sinister, as restrictions to halt the spread of the virus destroy people’s livelihoods and organs become a prized currency on the ‘red market’.

“The conditions are becoming more ripe for trafficking,” says Aimée Comrie, project coordinator at the GLO.ACT anti-trafficking initiative at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

Far fewer transplants have been performed over the past six months globally as hospitals closed or diverted resources to treating COVID-19, creating a significant backlog of patients on waiting lists.

Plummeting supplies have only added to an already increasing global demand for organs. Prior to the pandemic, less than 10 per cent of the global need for organ donations was met every year, a World Health Organization (WHO) spokesperson told SciDev.Net.

Meanwhile, wealth inequalities have sharply increased, leaving the poor still more economically vulnerable.

“That group of people who were already uneducated, uninsured, unemployed are now even more desperate to take up offers which they shouldn’t take,” says Comrie. “It just created a perfect storm.”

In recent years, organ ‘brokers’ had already used Facebook pages as a recruiting medium for the so-called red market. But the financial difficulties and restrictions on movement caused by the pandemic have turbo-charged this illicit use of the platform as a place for sellers to advertise.

Delhi-based Nandram (whose name has also been changed to protect his identity) lost his job as a youth hostel worker in April and is living with his parents again, which he calls “torture” as they vehemently disapprove of his homosexuality.

The 26-year-old posted his wish to sell a kidney on numerous Facebook pages, and says he has seen an uptick in similar posts since the pandemic struck.

The Facebook page which Nandram posted in, entitled Selling of Kidney, has been active for over a year. In the six-month period April to September since lockdowns began, comments from sellers more than doubled compared to the previous eight months.

Nandram says he has spoken to three people who claim to have sold kidneys through these networks in the past three months.

The page was among more than two dozen that SciDev.Net identified, most with names as obvious as kidney buyer or donate a kidney for cash. Comments from users since the pandemic began across this sample of pages have numbered well over 900.

International trade

The red market has both national and international forms.

The difference is often the degree of organisation of the brokers, the middlemen who take the lion’s share of the fees and coordinate between the medical professionals conducting transplants, recipients and sellers.

At the more sophisticated, international end, this is “very big business”, says Comrie.

Egypt has become known for both its highly localised organ trade, and as a prominent hub for international networks.

Recipients in the international networks have historically travelled to the country from wealthier Gulf states and surrounding African countries, often paying hundreds of thousands of dollars in a practice sometimes known as transplant tourism.

Comrie cautiously argues “it could be” that this practice has temporarily subsided due to the travel restrictions imposed this year. Ayman Sabae, a researcher at Cairo-based charity Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) also says it has been a while since he has received reports on organ trafficking.

But he insists that, overall, the trade has stayed the same because of weak enforcement of rules and the economically precarious situation for many.

Refugees in Egypt with limited working and social welfare rights — primarily Sudanese, Eritreans and some Syrians — are most vulnerable to the trade. Sabae says coronavirus has compounded the already severe financial vulnerabilities for them.

Seán Columb is an organ trafficking expert and a University of Liverpool lecturer in law. He also stresses refugees may bear the greatest cost of the pandemic in Egypt.

“The reason that I think migrants in particular are being targeted [by brokers] is they can’t find work,” he says.

Refugees already often find themselves barred from the job market, and Columb argues that rising unemployment and even less support from an Egyptian state crippled by the pandemic may force refugees to consider drastic options.

But the crisis will also affect refugees who had been planning to escape to Europe via the Mediterranean this year.

Since Egypt’s lockdown restricted activity on 25 March, until reopening in late June, recorded sea crossings dropped to 8,045 according to UN figures, compared to 16,198 last year — and the lowest for this period in five years. April saw the lowest monthly crossings on record, at 1,187.

But fewer crossings may only have made refugees more vulnerable to the organ trade, according to Columb.

On the one hand, smugglers’ prices have gone up because of greater border control, he says. On the other, the build-up of refugees arriving in Libya unable to travel to Europe due to travel restrictions may now mean a “two-to-three-month” wait for an available ship.

“And that ship may never come, then you’re in debt,” says Columb.

“[If] you’ve paid that money to the smugglers already in advance, you’re never going to get that back because it’s illegal,” he adds. “Because there’s more debt involved, they are being pushed to [these] further extremes.”

India was once one of the world’s hotspots for the international trade, before laws were tightened in 1994. But close family and spouses are allowed to donate organs, a legal loophole which has proven open to exploitation, as brokers forge documents feigning these relationships between sellers and recipients.

Partly because family ties are harder to prove for foreign recipients, central commands for international networks have moved more to neighbouring countries like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

In Kerala, South India, local sales are still “very, very common” says Davis Chiramel, a priest in the Southern Indian district of Thrissur and founder of the Kidney Federation of India, which works to encourage kidney donation after death.

He receives calls from people looking to sell their kidneys who have misunderstood the aim of his charity, and says he has seen a surge since the pandemic struck.

In the past six months, he has received two to three calls a day, or several hundred since India’s lockdown, which he claims is twice as many as during the same period in 2019. The vast majority, he says, are driven by financial difficulties.

The pandemic has also added to the growing demand. Sanjay Agarwal, head of nephrology at the All India Institute of Medical Science and convener of India’s National Transplant Registry, says the diversion of resources to treating COVID-19 means his public hospital still has not performed a transplant since March at the time of writing.

Yet at any one time, he says, India needs around 300,000 renal transplants — a number climbing year-on-year because of rising hypertension and diabetes. Only 8,000 transplants were performed in the country last year, and supply is not increasing, meaning a huge unmet demand.

Liver, corneas and skin

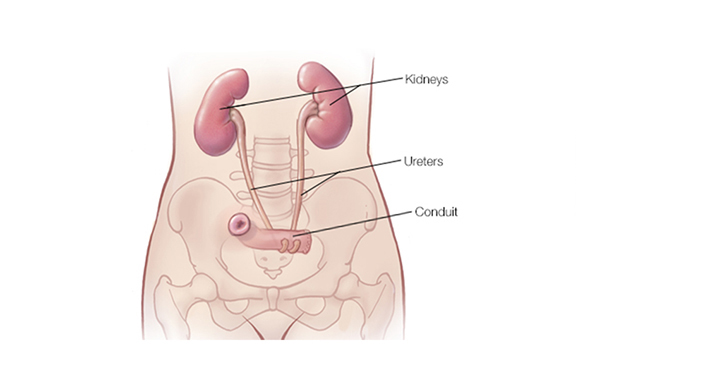

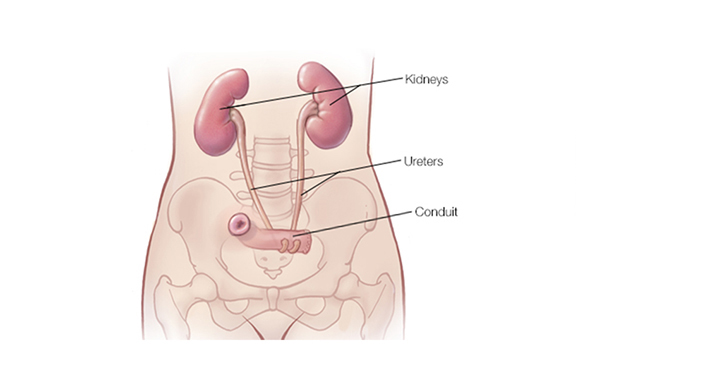

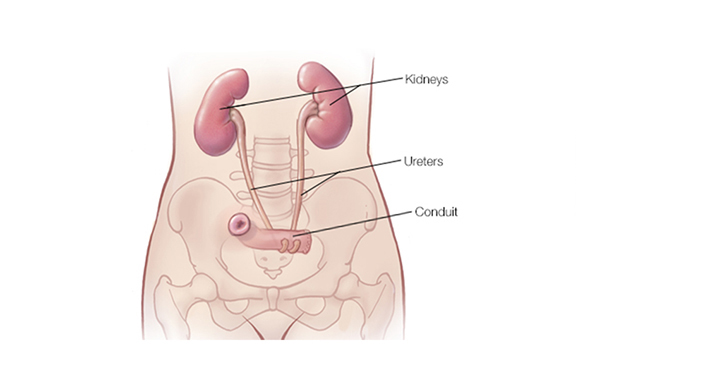

Kidneys are by far the most trafficked organ, though liver sales too are on the rise. Occasionally, unconfirmed reports also mention corneas, plasma and skin transplants.

The sought-after body-part: kidney. Image credit: Edgardo Sawyers, under (CC BY-SA 2.0) This image is cropped.

While illicit organ sales remain an issue all over the world, the sellers who supply both national and international red markets come disproportionately from countries in the global South.

“It’s still a big problem in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Egypt — maybe Syria,” says Debra Budiani-Saberi, founder of Coalition for Organ-Failure Solutions (COFS), which promotes advocacy, prevention of organ trafficking and support to victims globally.

As well as the Gulf, foreign recipients travel from places such as the United States and Europe for transplants. Sometimes they fly to third countries to which sellers are also transported, and from which these networks operate.

“Israel’s been renowned for its sophisticated international rings, in coordinating transplants in South Africa, with Brazilians, and in Turkey,” says Budiani-Saberi.

In one case which made headlines around the world, doctors at the Kosovo-based Medicus clinic were found to have carried out at least 24 operations in 2008. Recipients were largely from Israel and paid up to US$100,000 for the operation, while mostly low-income sellers came from Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Russia and received sometimes only US$8,500. Other reports show victims have received fees as low as US$2,500.

A 2013 OSCE report argues organ trafficking has been “growing over the last ten to 15 years” and the UN’s Comrie agrees, telling SciDev.Net: “In my view, it’s getting worse.”

While in theory organ sales can be consensual, Comrie admits she is yet to see a case without “deceit or fraud”, while she has seen a “good amount” of cases where victims are scammed and receive no money at all.

The typical victim, she says, is male, poorly educated, marginalised and from a rural area, and who is facing financial difficulties. Brokers will often lie and tell potential sellers things such as “your organ will grow back like a fruit on a tree”, she says.

As the coronavirus accentuates these vulnerabilities, a WHO spokesperson told SciDev.Net: “We need to remain vigilant and protect affected populations.”

According to WHO estimates from 2007, the most recent available, around five to 10 per cent of global kidney transplants annually are commercial — which would mean almost 10,000 last year.

The practice is legal only in Iran, where it applies just to nationals and the Iranian diaspora.

Budiani-Saberi says COFS has assisted around 250 victims of organ trafficking per year for the past five years. Though it identifies hundreds of victims each year, it does not have the resources to support any more than this.

She says that although the “clandestine nature” of this abuse prevents her from having accurate data on organs trafficked per year, she estimates it at least in “in the hundreds” and possibly in the thousands.

The UN’s most recent Global Report on Trafficking in Persons recorded around 100 cases of organ trafficking from 2014-17.

But Comrie calls this a “vast underrepresentation”, as figures are self-reported by member states when local authorities catch people involved in the illicit trade. She argues that the shame accompanying organ removal and criminalisation of victims prevents those affected from speaking out.

“No country wants it to be known that its citizens are selling their body parts to survive,” she explains, arguing NGOs are sometimes even disbanded for exposing these issues as national problems.

“Wilful blindness” by authorities who have other priorities also plays a part, while amateur trade in makeshift venues remains too underground to monitor.

“Most of the [data] gathering has been episodic by the occasional researcher who was studying at one place at one time,” adds Lawrence Cohen, senior medical anthropologist at UC Berkeley and co-founder of anti-trafficking organisation Organs Watch.

Ultimately, he says, it is “data no one wants”.

Loopholes

Experts say addressing illegal trafficking will not be easy.

Legislation and law enforcement is one problem. In India, the legal loophole persists while authorisation committees, in charge of monitoring live donations and clearing certain transplants, do not have the authority to check bank accounts for payments.

In Egypt, new legislation from 2010 banned commercial organ sales and imposed penalties for all involved, which were increased further by a 2018 law. But as EIPR’s Sabae argues, “it’s not a law that would be enforced on its own”, but “requires institutions, it requires resources, it requires work … it would require campaigns for public awareness”.

Comrie argues that law enforcement is not accustomed to organ trafficking cases and often struggles to investigate these complex crimes. She is leading the development of a UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) virtual simulation tool to be made available next year which will train police to detect key evidence at the scene.

Another option is to boost the supply from deceased donors, which in India for example currently make up just five to 10 per cent of organ transplants. Sumana Navin at the MOHAN Foundation, a non-profit organisation which seeks to encourage such donations in India, says deceased donations were especially important this year as the risks of spreading COVID-19 made it much more difficult for hospitals to conduct living donor transplants.

“Hospitals are proceeding with deceased donations because you’re losing the opportunity to save so many lives if you don’t go ahead. It’s an opportunity that’s never going to come back”.

Yet stigma sometimes persists around deceased donations.

As a solution, medical experts cite Spain’s opt-out rather than opt-in model for use of organs of those who have died, which the UK also moved to this year. But in countries such as Egypt, despite religious leaders now formally endorsing the practice, citizens have been reluctant to sign up.

Tackling the vulnerabilities of victims could also help eliminate organ trafficking, argues Columb, especially when it comes to refugees who sell their organs as a last resort.

“There should be resettlement and that’s not just for one country to do, there has to be real international solidarity,” he says, insisting relocation pledges by nations to the UN Refugee Agency’s resettlement programme need to increase.

Finally, there are few controls on the platforms used for recruitment.

Out of the Facebook pages that SciDev.Net found, some have been active for more than a year and have amassed over a thousand followers. Comments come from users all around the world — spanning India, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Africa and the Philippines.

“Social media has a responsibility,” says the UN’s Comrie, “if they were really devoted to tackling this it shouldn’t be that hard.”

SciDev.Net requested a comment from Facebook on the problem, but Facebook did not reply by the time of publication.

What is clear is that the pandemic has not just brought devastation through the millions infected, it has also created the deadly side effect of an ever more thriving organ trafficking industry.