08/01/24

Famine fears stalk Sudan as conflict spreads

By: Hazem Badr

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[CAIRO] Widening conflict in Sudan threatens to tip the country once known as the “breadbasket of the Arab world” into famine, analysts warn.

Nearly 18 million people in the north-east African country are already facing acute food insecurity, according to the World Food Programme, following the conflict which broke out in April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

Until now, eastern Sudan’s Gedaref state, which is a major producer of the staple food crop sorghum, has not felt the impacts of the conflict directly, says Hassan El-Awad, head of the Sudan office of the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA).

“We urgently call on all parties to the conflict for a humanitarian pause and unfettered access to avert a hunger catastrophe in the upcoming lean season”

Eddie Rowe, WFP country director in Sudan

But if the conflict spreads, food insecurity could become “worse than the indicators revealed by the World Food Programme”, El-Awad said.

Hotspots

“The impact may appear in the upcoming winter and summer cropping seasons, with some of these areas becoming conflict hotspots,” he tells SciDev.Net.

A shortage of agricultural labour required for planting and harvesting, and of agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilizers – disrupted by fighting – will likely affect yields of sorghum, which Sudanese people grind into flour to make bread, he explains.

More than 7 million people have been displaced by the conflict – 5.8 million internally and 1.5 million fleeing across borders into neighbouring countries – official figures show.

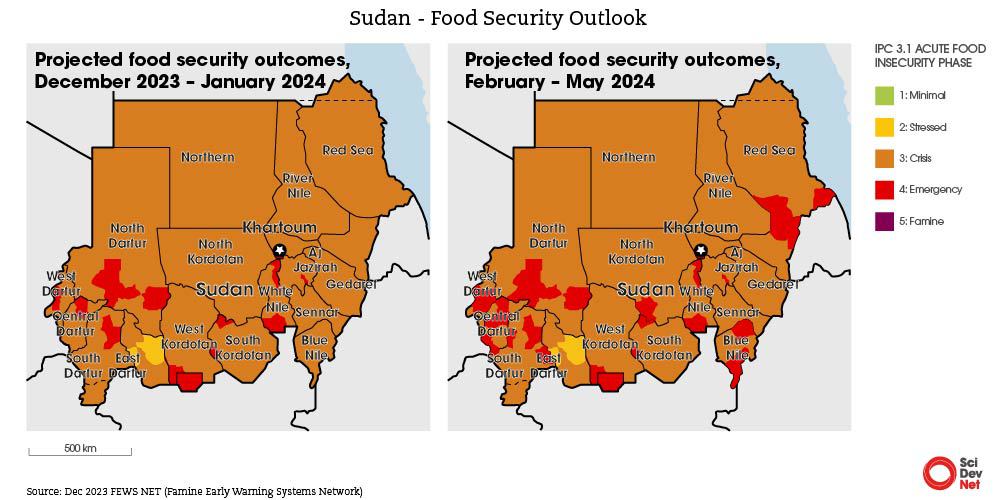

A report by the Famine Early Warning Systems Network, published on 6 January, says the expansion of fighting into parts of central and eastern Sudan is expected to lead to “considerable deterioration in acute food insecurity in the south-east”.

“The anticipated movement of the conflict into Gedaref, a critical location for national grain storage, adds to the alarm for serious supply losses and impacts on national food availability,” the report states.

Unprecedented

Analysis published by the WFP last month (13 December) shows the worst level of hunger ever recorded during the harvest season, which begins in October and lasts until February.

Prices of basic grains are expected to rise by 200 per cent compared to last year, according to the analysis.

Since 2019, the number of people facing acute food insecurity has more than tripled, rising from 5.8 million to nearly 18 million – almost two fifths of the Sudanese population – it says.

Of these,12.8 million are classified as being in catastrophic food insecurity, while 4.9 million are in an emergency food security situation.

If vital food assistance cannot reach conflict hotspots before the lean season begins in May, “catastrophic hunger” levels could arise, the WFP previously warned.

Almost 13 million people are already classified as being in catastrophic food insecurity.

As well as the challenges posed by ongoing fighting, aid efforts have been hampered by looting, including the theft of food supplies from a WFP warehouse in Gezira state last month.

“We urgently call on all parties to the conflict for a humanitarian pause and unfettered access to avert a hunger catastrophe in the upcoming lean season,” said Eddie Rowe, WFP country director in Sudan.

A study based on satellite imagery by the humanitarian organisation Mercy Corps, published last October, showed a decline in cultivated land in Sudan.

Elwathig Mukhtar, assistant resident representative of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Sudan, tells SciDev.Net cultivated land area had decreased by around 15 per cent from five years ago.

He said maize production was expected to fall by almost a quarter compared to last year and millet by half, “for reasons mostly related to the repercussions of the conflict”.

The areas that have been hit by the armed conflict are considered to be some of the most important areas for yielding crops and producing food in the country.

Government inaction

The Sudanese government had decided to cultivate more than a million acres in the states of Al-Jazira, the Northern, River Nile, and White Nile, according to a researcher in the Sudanese Ministry of Agriculture.

About 359 billion Sudanese pounds (US$597 million) was also allocated for the cultivation of winter crops, especially wheat, said the researcher, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals.

“However, this plan announced by the government shows no signs of implementation on the ground,” he said.

Since mid-December, the city of Wad Madani, the capital of the easterly Al-Jazira state, has witnessed violent clashes and air and artillery bombardment between opposing forces, which led to thousands of citizens fleeing the city, while local authorities declared a state of emergency.

Farmers there stopped growing wheat, knowing that harvesting crops would be too challenging.

“What kind of agriculture are we talking about in this atmosphere?” asked the researcher, adding: “We are heading towards a real famine, unless this conflict is quickly contained.”

Mukhtar warned that food security in Sudan had reached a “dangerous stage”.

The FAO has provided one million farmers in nine states with seeds to grow corn, millet, peanuts, and sesame. It will supply 88,000 farmers in January with inputs for producing vegetables.

The UN agency has also prepared an emergency plan outlining interventions to assist 9 million small-scale food producers across agriculture, livestock and fisheries, to provide them with production inputs in the year ahead.

“Implementing this plan requires US$104 million and we hope that the amount will be provided by donors,” Mukhtar added.

This story was produced by SciDev.Net’s regional office in the Middle East and North Africa and edited for brevity and clarity.