By: Vijay Shankar

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A device that can magnify tuberculosis bacteria without using a conventional glass lens could soon replace expensive lens-based microscopes in developing countries, according to a feasibility study published in the journal Tuberculosis.

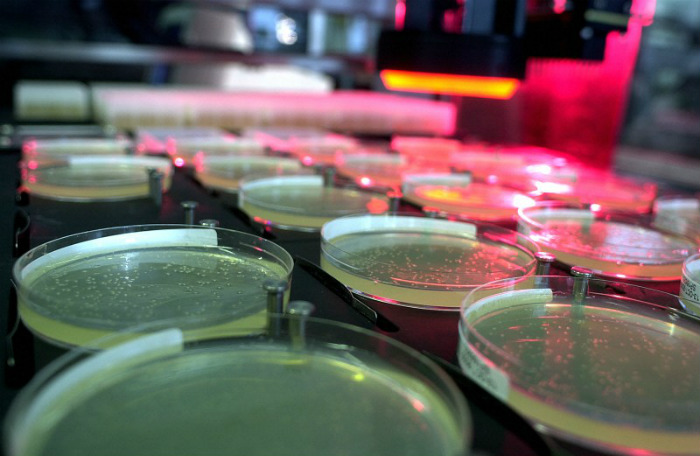

The gadget could diagnose tuberculosis in a sample within seven days, while also reducing the danger of lab technicians catching the disease, the researchers say. The microscope is connected to a computer using software that captures the patterns formed by suspected tuberculosis bacteria in a special petri dish.

Conventional tests require a technician to regularly take photos of the growing bacteria over a time period of 10-14 days, typically meaning a long wait before diagnosis, says Mirko Zimic, a diagnostics researcher at the Cayetano Heredia University in Peru and who is testing the device. And because the tests also expose technicians to an infection risk, only high-security laboratories can carry them out.

The new device automatically takes photos of samples in a sealed petri dish using an LED light and electronic sensor. “Incorporating the lens-free microscopy lets you do a completely automated identification of tuberculosis,” says Zimic. Because the device can take photos more regularly, it takes up to 7 days for this a diagnosis to be possible.

The team is working to further improve the microscope’s ability to automatically detect the typical clumping pattern of tuberculosis bacteria. In 2014, tuberculosis infected around 9.6 million people around the world (see chart).

The new device is based on a lens-free technology called ePetri developed at the California Institute of Technology in the United States. It magnifies bacteria in an airtight sample of phlegm by up to 60 times.

The device can also measure the bacteria’s resistance to antibiotics, helping clinicians to know if the disease is a multidrug resistant or extensively drug resistant form, says the study, which was published last month.

Automating the process of visualising tuberculosis bacteria could greatly speed up diagnosis of the disease, which is easiest to cure in its early stages, says Sarman Singh, a microbiologist at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

But Rekha Jain, who tests for tuberculosis at the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai in India, says the lens-free system would not be ideal in resource-limited settings where tuberculosis is endemic as it still requires a safe laboratory to avoid spreading the infection.“It is not a point-of-care test that can be used in the field,” she explains. “This can be used only in special centres and relies on highly skilled technicians.”

References

Leonardo Solis and others Evaluation of a lens-free imager to facilitate tuberculosis diagnostics in MODS (Tuberculosis, 21 December 2015)