Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

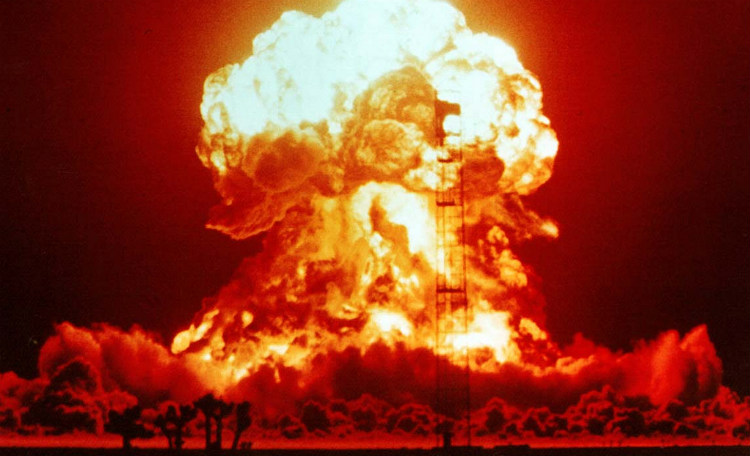

The international body that monitors nuclear explosions is trying to encourage more scientists from developing countries to make use of data derived from its US$1 billion nuclear explosion detection system.

The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), based in Vienna, Austria, relies on hundreds of seismic, hydroacoustic and radionuclide stations around the world to uncover evidence of possible nuclear tests.

At a conference in Vienna this week (22-26 June), the CTBTO will seek to show how data from this International Monitoring System (IMS) could support other areas of science, with applications ranging from meteorological modelling and tsunami warnings to studying the migration of whales.

Advertising this scientific value can help draw in governments who have limited interest in detecting nuclear tests, according to the head of the CTBTO.

“We are trying to attract more adherence among countries in the developing world,” Lassina Zerbo, the organisation’s executive secretary, told SciDev.Net ahead of the conference. “Nuclear testing monitoring is not their priority, so we have to see what the spin-offs are of the technology that we use.”

Under the treaty, which bans all nuclear explosions on Earth, each signatory state has the right to access all the data made available to the CTBTO’s International Data Centre in Vienna.

“We have to put this enormous amount of data at the service of the population, to study climate change, the Earth, the atmosphere.”

Gérard Rambolamanana, Institute and Observatory of Geophysics of Antananarivo

Thirteen nations have not signed the treaty, including India, North Korea and Pakistan. India is reluctant to sign the treaty until neighbouring Pakistan does so, and vice versa. In February, Zerbo wrote a column in Indian newspaper The Hindu, urging Indian institutions to begin science cooperation with the CTBTO.

“Science should support diplomacy,” he wrote. “This could eventually lead to India participating in the international exchange of data from the monitoring stations and would be an important first step to establishing familiarity and trust.”

The IMS constantly monitors unusual events underground, underwater and in the air. Its data sets span two decades, allowing researchers to study long-term phenomena.

“We have to put this enormous amount of data at the service of the population, to study climate change, the Earth, the atmosphere,” says Gérard Rambolamanana, who runs the seismology and infrasound lab at the Institute and Observatory of Geophysics of Antananarivo, Madagascar.

The CTBTO hopes the Vienna conference will encourage more researchers from non-signatory countries to seek partners that would allow them to access some of its data.

At the time of writing, nine representatives from India and 12 from Pakistan had registered to attend, out of about 1,000 participants. “We hope that they will carry the word back home” about the system’s value, a CTBTO spokesperson says.

Out of a budget of about US$130 million, the organisation spends about US$3 million a year on capacity building, outreach and training. Madagascar, for example, has hosted two IMS stations since 2001: one infrasound and one seismic facility.This has created training opportunities and helped build closer links between researchers nationally and internationally, says Rambolamanana. As a result, local science and technology have made a “big jump” forward, he says.

More on Nuclear

News

Jordan’s nuclear programme comes under fire

[AMMAN] Jordan's ambitions to become a regional nuclear research hub have encountered setbacks follow ...11/07/12