Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

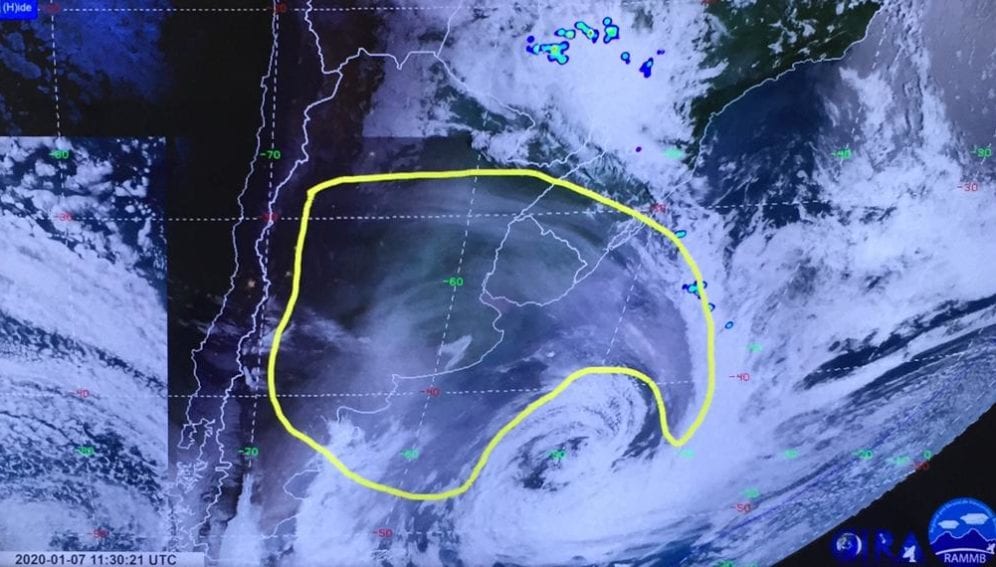

Smoke particles from the fires ravaging Australia have traveled more than 12,000 km, crossed an ocean and a mountain range and arrived in South America, meteorological institutions confirmed, after smoke was detected in Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay.

“From the afternoon of 6 January, a grey cloud and redder sunrises and sunsets could be seen in the sky [in Uruguay] due to the presence of small particles in suspension, more than 6,000 meters high, of smoke generated by the great fires in Australia,” said a statement from the Uruguayan Institute of Meteorology (Inumet).

Lucia Chiponelli, technical manager at Inumet, told SciDev.Net that despite the annual “bushfire season” in Australia, this was the first time smoke had been recorded arriving in Latin America in recent decades.

Fires raging in Australia since September have killed 24 people, destroyed more than 1,500 homes, and razed 6 million hectares of land, leaving more than 500 million animals dead. The bushfires, which are among the worst in the country’s history, have been fuelled by record temperatures — 41.9 °C on 17 December — and several months of intense droughts.

It comes after record fires in the Brazilian Amazon last year burned around 1 million hectares of forest between July and September, according to official statistics, while environmental organisations put the figure at more than double that.

NASA video shows the movement towards South America of a huge cloud of smoke from the Australian fires.One of the consequences of such fires is that when air is heated it rises to the upper layers of the atmosphere, dragging particles from the burned materials along with carbon monoxide and other compounds derived from combustion.

From Chile to Uruguay

However, the situation depends on many factors. Even if Australia’s fires persist at their current rate, the concentration of particles can be lessened by local circumstances. The smoke reached Latin America more than a month after the fires started in Australia, for example, after being dispersed by Pacific Ocean winds in its path.

Other factors, such as storms, may stop the smoke in its tracks. “The clouds that generate storms have a vertical development that can reach 6,000 meters high. If the particles enter those storm clouds they will precipitate with the rain. Then, if storms form on the road over the ocean or when entering Chile, the particles do not arrive,” said Chiponelli.

Health and airplanes

How can we predict fires?

Results showed that the areas of greatest risk are within a radius of 2,000 metres of urban areas, a sign that many of the fires are started by local people.