Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Located on the Atlantic coast, Cameroon’s Ebodjé village is known for its lush landscapes and proximity to the Campo-Ma’an National Park, rich in wildlife and flora.

Campo-Ma’an is on Cameroon’s list of sites to be considered for world heritage listing and is close to the Manyange na Elombo-Campo marine park, the breeding site of a number of endangered sea turtle species.

But this ecologically important part of southern Cameroon is set to become the site where Chinese mining company Sinosteel, through its subsidiary Sinosteel Cam S.A., will create the Lobé iron ore mine.

Indigenous communities say the mine will threaten the cultural and religious heritage of Ebodjé village and its ecosystems, critical species, and food and water sources.

Sinosteel declined to discuss the project and its potential consequences with SciDev.Net, while Franck Mene, communications manager at Sinosteel Cam S.A., told SciDev.Net: “We are not communicating at the moment. I would appreciate your understanding of our current unavailability.”

Meanwhile, an absence of public consultations has left Cameroon’s southern communities worried about their futures. “We are like an earthworm surrounded by ants,” the chief of Ebodjé village, Njokou Djongo, tells SciDev.Net.

Lobé iron ore mine

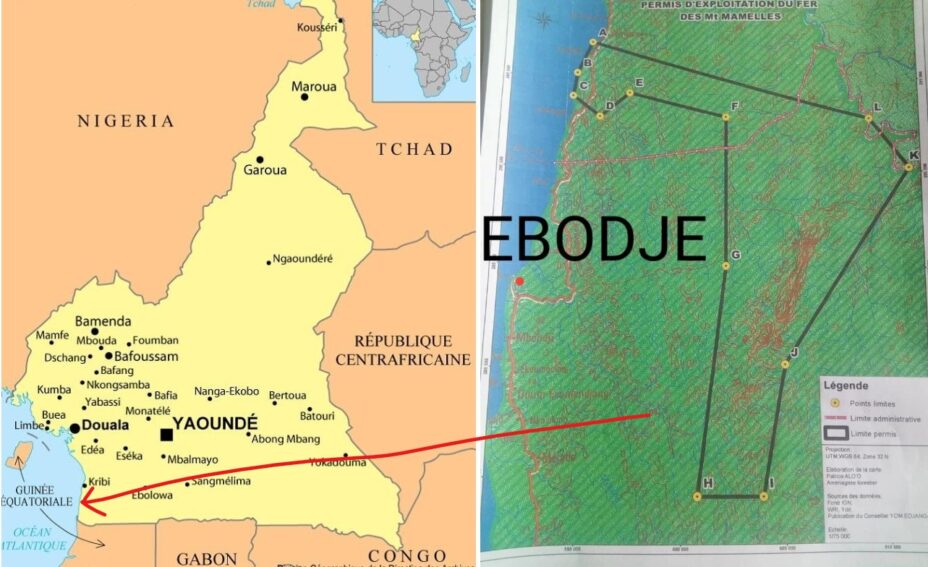

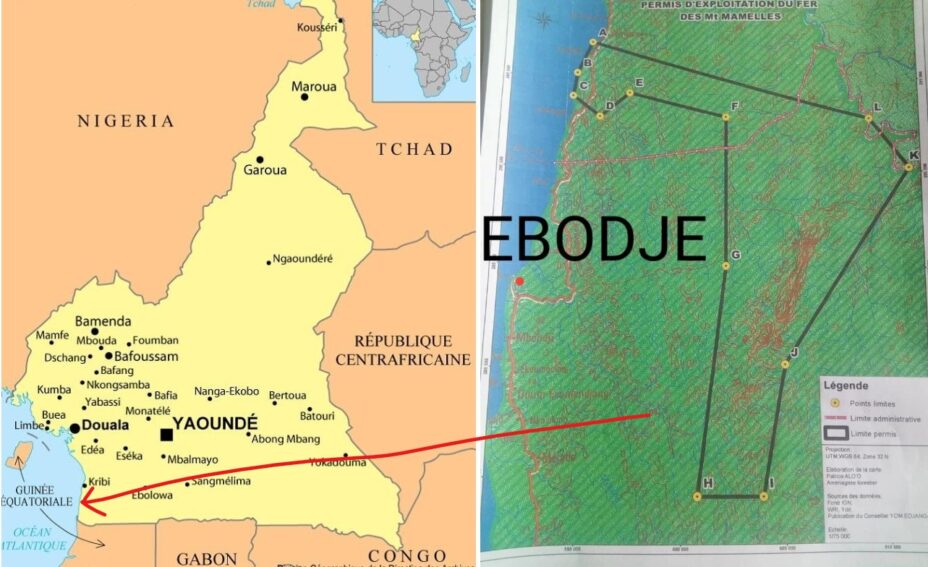

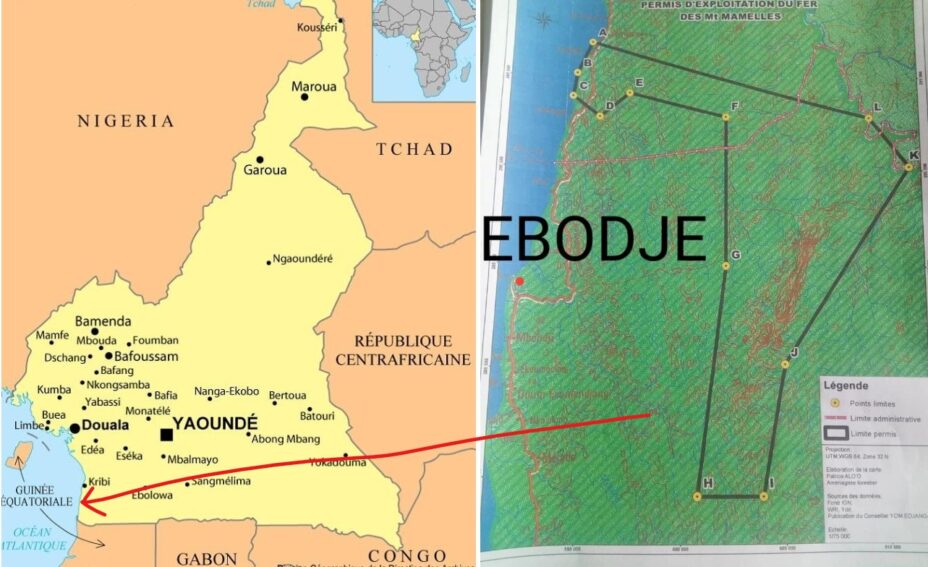

The Lobé iron ore mining agreement was signed on 6 May between Cameroon’s mining ministry and Sinosteel Cam S.A. The Lobé mine will be located 200 kilometres south-east of the capital Douala, and 40 kilometres from the seaside city of Kribi.

According to the signed agreement, Sinosteel Cam S.A. plans to extract ten million tonnes of iron ore per year, which the company will enrich to produce four million tonnes of high content iron ore. The agreement allows for 85 per cent of the iron ore to be exported – but the 15 per cent earmarked for the local market could be approved for export if demand is too weak.

The location of the mine in the village Ebodjé, on the Atlantic coast of Cameroon.

The agreement allows for the continuation of exploration activities within the perimeter of the mining permit, which covers 138.5 square kilometres and there are fears it could impact the 2,680 square kilometre Campo-Ma’an National Park as well as the Manyange na Elombo-Campo marine park, which covers 1,103 square kilometres of the Gulf of Guinea.

The agreement claims the project will create “at least 600 direct jobs and more than 1,000 indirect jobs”.

Despite the mining convention’s approval and a subsequent presidential decree, local communities say there have been no consultations or public hearings – leaving no room for residents to voice their concerns.

Consent ‘critical’

Conversations about signing off mining conventions should not even begin before communities are allowed their say, according to Bareja Youmssi, a petroleum geosciences specialist and lecturer at Cameroon’s University of Bamenda.

The villages that will be affected by the mine are part of the Yassa community, one of the hundreds of indigenous Bantu groups who live across southern and central Africa.

Under the non-legally binding United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, communities should be allowed to give or withhold consent for projects affecting indigenous peoples or their territories – a right known as free, prior and informed consent. Cameroon has not ratified the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, a legally binding international convention that preceded the UN declaration.

“There should have been a consultation with the community first, before signing the agreement; this was not the case,” says Youmssi, a specialist in mining contract negotiations.

Osman Aoudou, president of the Mining Engineers Association of Cameroon, agrees. “We have been taught that consultation of local populations during mining projects must be done from the research phase,” he says.

René Noungang, the Cameroon delegate of the biodiversity and conservation charity Emergency Planet (Planète Urgence), says that without free, prior and informed consent, a mining agreement cannot be reached, as the project is not fit to be implemented.

However, Article 106 of Cameroon’s mining code provides for community consultation to take place after an agreement has been signed, rather than before. “In all countries, hearings with indigenous people take place before the signing of the convention; but in Cameroon it is the other way around. This is why the current mining code is obsolete and must be reviewed in its entirety,” says Youmssi.

Aoudou says the policy may be based on political, economic or technical considerations. “To attract investors, you need to reduce the demands and facilitate the work, especially during the research phase, which is an activity with very high risks for the operator,” Aoudou tells SciDev.Net. “Intense and repetitive public consultations can not only slow down the work but also lead to loss of money.”

Environmental consequences

The Lobé iron ore mine could include an open pit, which will degrade the soil and subsoil of the area, according to Aoudou. “A large pit or several wells with an average depth of 200 meters – depending on the burial of the deposit – will be dug in the ground in order to extract the ore,” he says.

Environmental risks are present at several stages throughout the project, according to Aoudou. He says that the installation of site facilities will involve deforestation and changes to arable land which could lead to a drop in agricultural production in a region where the population lives mainly off farming.

Once operational, the mine will discharge waste rock and other residues such as fine particles, dust, oils and fumes from machinery. “These discharges constitute a risk of contamination or pollution of the soil, surface water, groundwater, air, surrounding fauna and flora,” says Aoudou.

Sea turtles are part of the wealth of Ebodjé. Copyright: M. Ngomi

Indigenous communities

Ebodjé village chief Njokou Djongo says that his community is not against state projects, but he does not approve of the government’s approach.

The plans show that the mine is expected to straddle two villages, Ebodjé and Lobé, with the majority in Ebodjé. As the communities have not yet been consulted, little is clear regarding the displacement of populations.

“I have the remains of my parents, ancestors and certain members of my family, buried in my yard. You can’t destroy all that for the sake of a few bucks. It hurts,” Djongo says. Noungang notes that if bodies are exhumed to accommodate the mine, it could create a resurgence of emotional shocks, followed by “serious” social consequences.

For the region’s indigenous communities, the Lobé mine could also have significant cultural and religious impacts. On the 138.5 square kilometres of land to be exploited as part of this project, native people say they have trees that should not be cut down because they are sacred.

Similarly, they fear the loss of “mythical rocks, turtle rocks and other things a little deeper like the caves which [could] be blasted with dynamite“.

Didier Yimkoua, the national coordinator of the environment non-profit World Action Phyto Protection, says the forest is home for Bantu peoples, as well as sacred and wild animals that must be given time to migrate.

Yimkoua likens the value of the forest for rural communities to supermarkets in urban areas – the forest is the source of food, daily necessities and even medicine.

But according to Yimkoua, the mine will affect every community in Cameroon because “they are increasingly resorting to traditional medicines due to the success of natural products in the fight against certain diseases”.

Petition and assessment

The Ebodjé community launched a petition in May to express their dissatisfaction with the mine’s approval and to call on the government and Sinosteel to take their concerns into account.

The petition noted that the village has not benefited from other national resources, such as “drinking water, electricity, technical training structures and paved roads”.

The community warned of the potential environmental devastation of the mining project, including massive damage to biodiversity and ecosystems, “the expropriation of arable and subsistence land”, “socio-cultural disorganisation as well as the destruction of social cohesion”, “the scarcity and depletion of food as well as the violation of ancestral sites and remains” or even “the gradual disappearance of rare species, protected sea turtles and natural tourist sites”.

Chief Djongo says that the community is yet to receive a response from authorities regarding their petition.

Observers say that there is no evidence that an environmental impact assessment has been carried out. SciDev.Net contacted regional officials, who declined to be interviewed, leaving local communities saying they feel “more and more alone” in the face of the mining project.

But Mckey Ngomi, who grew up in Ebodjé and now lives in the region’s main city of Kribi, tells SciDev.Net that an assessment is critical, as five of the world’s seven species of sea turtles lay their eggs on the beach of this locality every year. He says these include the leatherback sea turtle, green sea turtle, and loggerhead sea turtle.

The Campo-Ma’an park was created in 1999 to offset the biodiversity losses and environmental damage caused by the Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline Project. It is considered one of the world’s rare ‘biodiversity hotspots’, containing about 1,500 species of plants including 114 endemic species, 80 large and medium mammals, 390 invertebrates, 249 species of fish, 112 reptiles, 80 amphibians, and 302 birds.

Questioned by SciDev.Net, Ministry of Tourism delegate Gabriel Barka said that he was waiting on public consultations – but that he does not know when these hearings will take place.

“We are waiting. The sectors concerned are hard at work. When I talk about sectors, I am referring to the various ministries involved in the matter. It’s a bit early to talk about the case,” he said.

Uncertain future

A delegate at the environment and sustainable development ministry in Kribi says they are aware of the project’s risks.

The project called “Túbè awú’” aims to protect rare species of sea turtles. Copyright: N. Djongo

“This is not the first time that Cameroon has faced this kind of challenge. The environmental and social impact study will indeed take place. Public consultations and public hearings too. It is not a favour but a duty for the state. People have to be patient. There is nothing to worry about”, says Jean Daniel Mewoli, head of the conservation and environmental monitoring office at the departmental delegation of the Ministry of the Environment in Kribi.

Little reassured, Noungang from the non-profit Emergency Planet says that it is not enough to produce an environmental and social impact study and an environmental and social management plan; it needs to be done “honestly”. Most of the time, he says, large documents with biased information are produced and then ignored, and it is populations and biodiversity that suffer.

At Sinosteel Cam S.A., communications manager Franck Mene appears unnerved: “The signing of the operating license will, we are sure, open up more opportunities for us to move around”.

This article was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa French edition