Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The UN Convention to Combat Desertification needs to support local action for it to be effective, says Camilla Toulmin.

In 1992, delegates to the UN Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio agreed that a desertification convention was essential to solve the problems of poor, dryland countries. As a result, the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) was established in 1996.

Ten years on, the UNCCD has tied national governments into a series of high-level meetings that are far removed from real issues on the ground. If it is to make progress over the next ten years, it needs a fundamental re-design.

Life is still getting tougher for dryland dwellers

Dryland dwellers traditionally use farming practices adapted to low and very variable rainfall. They grow several crop varieties and diversify their non-farming activities to cope with variable yields. They move livestock between wet and dry season pastures to avoid over-grazing around village settlements. Increasingly, they grow cash crops like cotton or groundnuts to make ends meet and invest in a better future for themselves and their families.

Yet for many farmers and herders, life is still becoming tougher. Available land is growing scarcer as populations rise and outsiders buy it up for agribusiness, wildlife ranching and tourism development. Traditional livestock paths are becoming blocked, making it harder for pastoral nomads to move herds from wet to dry season pastures. Cash crops are facing unfair price competition from subsidised farmers in developed countries, particularly those in North America and Europe. And, with global climate change, drylands are likely to face increasingly uncertain weather.

But poverty and destitution is not inevitable in drylands. More than 20 years of experience with partner organisations in many dryland areas have shown me three areas where the UNCCD could help ensure a more prosperous and secure future for these communities.

Steps forward

First, the UNCCD needs to bring the desertification and climate change agendas closer together. Climate change may already be affecting many of the poorest dryland countries. For example, the last twelve months brought prolonged droughts followed by exceptionally heavy rainstorms to East Africa.

There is a real need to invest in effective soil and water conservation. Climate scientists cannot predict exactly how regional rainfall will change, but even if more rain falls, higher temperatures will lead to more evaporation.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol are the main international tools for combating climate change, and negotiations are already underway for the period following 2012. Over the next ten years, the UNCCD will need to work closely with the convention on climate change to help dryland countries adapt. They could also explore opportunities for developing countries to sell carbon permits to richer countries that may have exceeded their Kyoto targets.

Second, the UNCCD should involve local communities in decisions about how aid is distributed. Increasingly large aid donations are channelled through World Bank poverty reduction strategies and plans that aim to improve health and education as part of the Millennium Development Goals.

But this highly centralised approach concentrates power and resources in national capitals, away from rural communities. There is little investment in agriculture or sustaining natural resources, for example through soil conservation programmes.

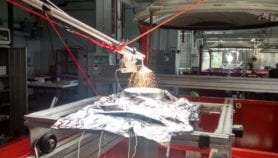

The UNCCD needs to invest in local-level activities, such as modernising indigenous techniques to collect and distribute water, or setting up tree nurseries that are managed by communities to stabilise soils and limit erosion.

Put simply, the convention needs to move away from top-down, government-led national action programmes that have little credibility at local levels, and towards more accessible and innovative support for dryland people, many of whom are already actively trying to improve their incomes and welfare. Such a shift should be easy for the UNCCD, which already enjoys good links with community organisations.

Third, the UNCCD should be securing people’s rights to the land and natural resources they depend on. In many developing countries people who live or work on the land have few ownership rights. They cannot use land as collateral for loans, so have no way of raising capital to expand their businesses.

Improving these rights will need to be tackled through existing political and legal processes (rather than setting up new laws). And such action requires a mindset shift, from seeing local people as victims needing to be rescued to recognising their rights as citizens able to manage their own development.

Many dryland dwellers are already preparing to adapt to the changing climate, improving their incomes and investing in their lands, for example through innovative water-sharing schemes, small-scale sustainable agriculture, and plans to re-forest degraded land. But they could do with more support.

If the UNCCD is to become more effective, it needs to follow this lead and focus on supporting local action.