21/08/20

AGRA ‘fails to deliver on promise to double yields’

By: Inga Vesper

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Large agricultural development programmes have done little to reduce hunger while pushing farmers into debt, food security experts say, as they warn that such schemes risk failure if they do not move away from industrial fertilisers and seeds.

A range of critical voices have spoken out against the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), an organisation launched in 2006 with the aim of delivering high-yield intensive agriculture to Africa via access to markets and credit, high quality seeds, and better soil health and agricultural policies.

False Promises, a report from a coalition of international development organisations, argues that AGRA missed its 2015 goal to double the productivity and incomes of 30 million small-scale food producers by this year, saying that AGRA’s initial goals were to double incomes for 20 million farming households while halving food insecurity in 20 countries by 2020.

“[Farmers] are treated as mere consumers of the seeds and services that the programmes and their partner companies provide, even though these programmes depend on the biodiversity and knowledge that farmers have developed over generations.”

Susan Nakacwa, GRAIN

The report is based on a study by Tufts University researchers, who say AGRA declined requests to provide internal monitoring and outcomes evaluation data. Instead, researchers used country-level production, yield and land data to assess whether AGRA programmes had significantly raised agricultural productivity.

AGRA’s 2017-2021 strategy states it will “contribute” to doubling the yields and incomes of 30 million smallholder households — nine million directly and 21 million indirectly.

In a statement to SciDev.Net, AGRA says it reached 4.7 million farmers in 2019. The alliance disputes accusations that its approach is failing Africa’s farmers.

Hunger vs yields

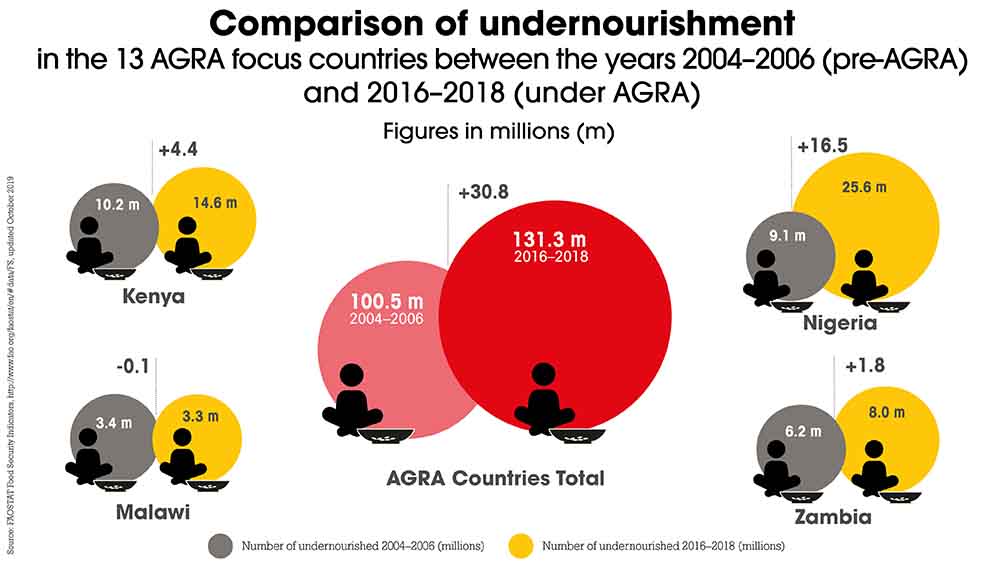

From AGRA’s launch to 2018, the number of people suffering undernourishment increased by 30 per cent across the organisation’s 13 focus countries, the report’s data shows. Farmers also reported going into debt when buying the seeds and fertilisers eligible for AGRA financial support.

AGRA says that hunger has been increasing globally since 2014 and rises in Africa are “due to factors that are beyond AGRA’s control”.

“These include fragile security situations, the impact of climate change and now, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic,” Aggie Asiimwe Konde, AGRA programme innovation and delivery vice president, tells SciDev.Net.

Roman Herre, agriculture advisor at the Food First Information and Action Network (FIAN) and contributor to the False Promises study, tells SciDev.Net that AGRA’s major shortcoming is its attempt to increase crop yields through methods used by large-scale industrial farms in wealthy countries.

“The idea that a small-scale farmer with double yield has twice as much money in her pocket is simply rubbish,” he says. “Even if you harvested twice the amount, much of the money needs to go back to the agricultural corporations.”

|

|

AGRA is funded through philanthropic donors — the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation had given US$661 million by 2018 — international governments and the African Development Bank. Its main countries of operation include Ethiopia, Ghana, Mali, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique.

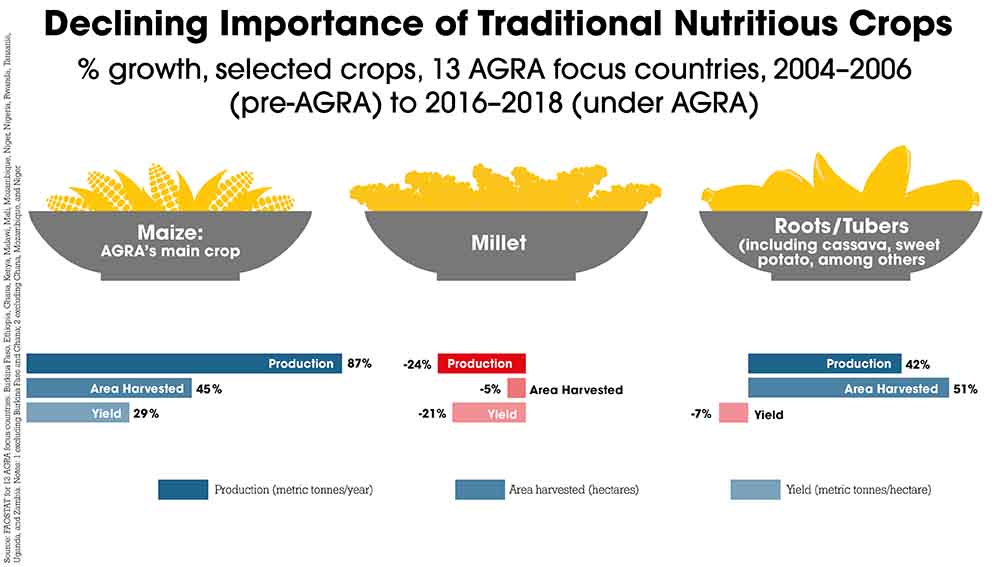

Timothy Wise, senior advisor at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy think tank, is scathing about the fact that much of the yield gains touted by AGRA were achieved by expanding the amount of land under cultivation, not by boosting yields per hectare.

Wise’s working paper, Failing Africa’s Farmers, which informed the False Promises report, notes that maize production in AGRA focus countries increased 87 per cent in the 12 years to 2018, but this was largely due to a 45 per cent increase in area harvested — meaning productivity increased 29 per cent, short of the promised 100 per cent.

Local loss

The overreliance on industrial seeds can lead to the loss of local, more climate-resilient crops such as millet, nuts, sorghum and tubers, according to the False Promises report. These commercially bred hybrid varieties yield even less if farmers use kernels from their harvest, Wise points out.

“So not only do farmers have to pay for the new seeds, they have to do so every year,” he tells SciDev.Net. “They often buy such inputs on credit and if they get a bad harvest they have no money to pay off the loans.”

Claims that farmers are being pushed into debt are “simply untrue”, Konde says.

“There is no evidence behind the suggestion that AGRA’s approach forces farmers to go into debt, not least as AGRA does not lend money to farmers,” she says.

“AGRA believes above all in farmer choice and opportunity, and rejects the view — often coming from outside the continent — that farmers should not be given access to the things they need and wish to use to improve their farms and livelihoods.”

Farmer input

Farmers are not consulted on the design and execution of these large-scale agricultural programmes, says Susan Nakacwa, a programme coordinator for the small farmer support organisation GRAIN.

“They are treated as mere consumers of the seeds and services that the programmes and their partner companies provide, even though these programmes depend on the biodiversity and knowledge that farmers have developed over generations,” she tells SciDev.Net.

“The companies can only profit when farmer seed systems and local food systems are destroyed and when small farms are pushed out by large industrial farms. This is simply a dead end for Africa.”

Konde says AGRA engages farmers directly and via national governments, which develop agricultural priorities for their own territories.

“We are able to work at scale and reach a large number of farmers — in 2019 we reached 4.7 million — and receive very strong feedback and direction from farmers across all our countries of operation,” Konde says.

“We hear farmer and [small and medium enterprise] voices through our village-based advisor system, and work closely with farmers’ organisations and cooperatives to meet the needs of diverse local communities across Africa.”

Wise says that large-scale programmes have a role in providing funding and support at a scale many poorer nations cannot provide on their own.

But, he says that investment needs to go towards affordable and sustainable practices.

Nakacwa agrees. “An entirely new approach is required,” she says. “One based on agroecology and food sovereignty.”