By: Nick Kennedy

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Pharma giant Merck has become the latest drug company to share intellectual property rights with a UN-backed patent pool for HIV medicines, but critics have told SciDev.Net it is “a false solution to a real problem”.

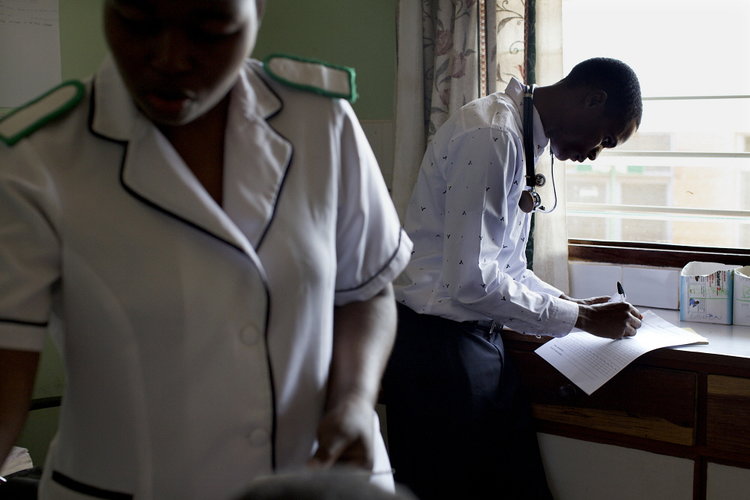

The Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) was founded in 2010 by UNITAID, a UN-backed initiative aiming to use innovative financing to increase access to HIV, tuberculosis and malaria medicines in developing nations. The pool lets drug manufacturers in developing countries produce and sell low-cost HIV treatments through voluntary licensing and patent pooling.

The MPP and Merck signed a licensing agreement last month (24 February) for paediatric formulations of raltegravir, one of the few HIV drugs approved for children younger than three. Using the new licence, drug manufacturers can make cheaper versions of raltegravir because they do not have to pay royalties to Merck, says Greg Perry, executive director of the MPP.

Another goal of the pool is to enable manufacturers to produce fixed-dose combination medicines of more than one drug in a single pill, he says. These are particularly valuable for treating HIV, where often three or four drugs are used at once.

“We’ve been able to pool all the key paediatric HIV medicines that have intellectual property protection so the drugs can be improved and combined to make new formulations in 92 countries, including those with the world’s highest HIV burden,” says Perry.

PR exercise?

But intellectual property expert Othoman Mellouk is critical of the agreement. Mellouk, who works at the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition, a global network dedicated to affordable healthcare for people with HIV, says he thinks the agreement looks like a PR exercise that will not deliver improved access to medicines where they are most needed.

“What we need for children with HIV is better drugs, better formulations, and we need to have them developed much more quickly.”

Martina Penazzato, WHO

He notes some middle income nations including China — which have more competitive pharmaceutical industries — are excluded.*

“The MPP mechanism ensures originator companies are in control and determine the parameters of agreements. Licences are negotiated without transparency. And there is little evidence of actual improvement in access to medicines,” he says.

Mellouk adds: “Coming from the Middle East and North Africa, I don't understand why a country like Morocco is included while Algeria or Tunisia are excluded. The countries have same economic situation and the same epidemic.”

He also thinks that drug companies use MPP agreements to bypass the existing legal mechanisms designed to protect access to medicines and public health, such as the World Trade Organization’s Trade-Related Aspects of International Property Rights (TRIPS), an international agreement setting out minimum standards of intellectual property protection.

Importantly, says Mellouk, many developing nations are afforded flexibilities under TRIPS. “If this is respected, there’s no need for a licence from the MPP,” he says. In fact, he adds, voluntary licences such as those agreed through MPP actually undermine a country’s negotiation power and ability to use TRIPS flexibilities.

However, a spokesperson for MPP tells SciDev.Net that their licences are compatible with TRIPS flexibilities.

Wrong answer

Tahir Amin, director of I-MAK, a US-based non-profit organisation that aims to increase access to medicines through a fair patent system, says the real problem with children’s antiretrovirals is not patents, but a lack of return on investment which means companies are happy to license generic companies and the patent pool.

“By controlling the competition to restricted licensed countries, the originator companies achieve their objectives. The patent pool is merely cementing the pharmaceutical company’s strategy of market segmentation which will in the long term be a detriment to the growth of generics, especially in India, supply chains and more importantly access,” he tells SciDev.Net.

But Martina Penazzato, paediatric advisor for the WHO’s HIV department, is more positive about the agreement: “What we need for children with HIV is better drugs, better formulations, and we need to have them developed much more quickly.”

*This article originally stated incorrectly that India was excluded from the agreement.