By: Anita Makri

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

FAO’s move to shore up the rights of small-scale fishers is making waves in Costa Rica.

In August 2015, the government of Costa Rica received a letter from a tiny fishing community on the northern Caribbean coast.

Nestled between Tortuguero National Park and the Nicaragua border, the community of Barra del Colorado — some 2,000 people — have been quietly making a living out of shrimp fishing for generations.

The letter took issue with a 2013 constitutional vote to a ban trawling — a fishing method that can damage marine environments by pulling along undesired fish species and destroying habitats at the ocean bottom.

The vote targeted industrial and semi-industrial trawling operations. But it made no exception for fishers operating at a smaller scale, to catch fish for food or to sell locally for a basic income. For Barra del Colorado and similar communities, it meant losing the legal right to their only livelihood, and a way of life.

“In this place this is the only work we can do,” says Ligia Mejia Guzman as she deftly cleans the day’s catch, shrimp by shrimp. The work, which occupies most women in the community, is without social security, leaves fingers bleeding as acid wears off the skin, and earns her about 20,000 colones (US$35) each day — on a good day — for two short fishing seasons a year. She learned it as a child and, like the rest, she is thankful for it.

The letter marked the beginning of a fight for the licence to fish, which continues today. One of the community’s allies is CoopeSoliDar R.L, a local development NGO that facilitated a consensus-building policy process — the National Dialogue for the sustainable use of shrimp — involving government institutions, NGOs, and all productive fishing sectors.

“We have been dealing with conflicts at the grassroots level, very serious conflicts, trying to get an equilibrium between marine conservation and the sustainable use of these resources that bring development to a lot of people,” says Vivienne Solis Rivera, a biologist with CoopeSoliDar.

The NGO is working in Barra del Colorado to build the community’s capacity to reclaim their licence. That means research, workshops, getting organised to have a voice in policy discussions — work that Solis Rivera says in recent years has had a boost from a new addition to the toolbox: a set of International Guidelines on Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries adopted by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) in June 2014.

The product of a long consultation with over 4,000 stakeholders from over 120 countries, the guidelines are “the first international instrument dedicated entirely to the immensely important — but until now often neglected — small-scale fisheries sector”, according to FAO. They emphasise the rights of artisanal fishers and offer guiding principles for governance and development of the sector.

Costa Rica is by no means unique in overlooking small-scale fisheries. But FAO believes it is the only country to make the guidelines, which are voluntary, a part of its national development plan. This makes it a case the UN agency is keen to watch.

Troubled waters

The effort has been controversial, going head-to-head with the country’s strong drive for conservation that has seen over a quarter of its territory designated as protected land.

“There is a real conflict with the environmental agenda,” Solis Rivera says, pointing out that high-profile campaigns have tipped the scales considerably. She believes the guidelines have added a crucial counterweight to that: for CoopeSoliDar and the national fisheries management body, INCOPESCA, having them in hand has meant the community’s concerns get more weight in policy. They give small fishers a presence; and this, she says, makes them disruptive.

According to Nicole Franz, a fishery planning analyst who leads FAO’s work on the guidelines, such conflicts aren’t unusual. “We do see that at times there are tensions”, she says, citing a lack of dialogue between the agencies and NGOs leading the different agendas. Her hope is that the guidelines offer a “basis for constructive collaboration”.

At a meeting convened by FAO last year at the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Center in Italy, delegates from around the world agreed to work towards indicators to monitor implementation of the guidelines through pilot projects.

Solis Rivera, who took part in the meeting, believes the guidelines can make a difference by “concretizing” a range of issues relevant to policy that affects small fishers. “When the guidelines were approved [in Costa Rica], we were able to really get a tool that could be used to provide more inputs of the need of this approach that considers human rights as the main backbone of conservation,” she says.

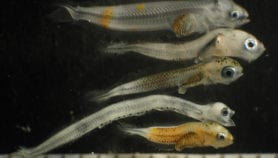

The fishermen who take their boats out a few kilometres away from Barra del Colorado, just where the mouth of Rio Colorado meets the Caribbean sea, catch only the amount of shrimp they can sell to middlemen in the area, plus a small percentage each for their families.

They ‘know’ that their nets don’t drag along as much fauna as other trawlers. Yet it takes studies to persuade Costa Rica’s government — and that’s what the community has set out to do, with help from CoopeSoliDar.

Solis Rivera says the guidelines have helped secure the time and money needed to do the research. Since February, through a temporary ‘research licence’, the men have continued to fish legally while gathering information about the sustainability of their practices.

That licence is due to expire soon. At a meeting last week, the community heard that early results of a study commissioned by CoopeSoliDar are promising.

Hanging in the balance

When it comes to the evidence on trawling, Solis Rivera says the devil is in the detail: in some cases semi-industrial fishing is less damaging than a fleet of small trawlers. She argues that the answer isn’t to ban trawling outright, but to manage it and look at the specifics of each case.

“Trawling by small boats along the coast is indeed different from trawling by large industrial boats,” says Tony Charles, a professor and research fellow at Saint Mary's University in Canada, and Director of the Community Conservation Research Network. He agrees that the right approach is a mix of measures depending on the fisheries, species and what works in a particular area.

Jesús Chavez, president of the fishermen’s association and lead signatory on the letter that protested the ban, says “the conditions in the Caribbean are very different [from elsewhere in the country], and the productive activity is very different”.

Jorge Jiménez is director of MarViva, one of the local conservation NGOs that favours the trawling ban. “There is no evidence that grants an exception,” he says, adding that research clearly shows the technique harms the environment as well as the resource that artisanal fishers depend on.

Jiménez says conservation should be focused on the long-term well-being of communities, but argues this cannot be built on destruction of marine resources. “A revision of existing fishing practices … providing better prices for [fishers’] products … and ensuring the well-being of the ecosystem is the balance we need to achieve.”

Charles says fishers can be trained to switch to new methods – but if trawling is the only way, it’s important to compromise and work with them to reduce its impact. “Conservation cannot be achieved through one action” like a trawl ban, he says. “Should a government be so rigid in a trawl ban that it hurts those who most understand the coastal marine habitat and who are most likely to care about conserving fish and ocean? That does not seem the best path.”

Information and power

Other communities are also struggling to get an official licence to fish. A group of women mollusc gatherers in Chomes, a fishing community of some 3,000 people on the country’s Pacific coast, have secured a licence for just one of the four species they can harvest.

With the help of CoopeSoliDar, they’re now organised, routinely recording data on the mollusc species in their mangroves.

The docking area in Chomes, a fishing community of 3000 people near Puntarenas, on Costa Rica’s Pacific coast. The coast has a mix of developed areas where tourism thrives, and underdeveloped areas where poverty persists.

Anita Makri

Fishing nets rest in piles along the riverbank. The men of the community have a licence to fish and sell their catch locally. But there is no formal recognition of the women who gather molluscs from the mangrove.

Anita Makri

Clams pulled fresh from the mangrove. According to the local NGO CoopeSoliDar, the environment ministry, which has jurisdiction over the area, needs research on the species being collected to grant the women a permit. They can now legally extract just one species.

Anita Makri

Women members of a cooperative association formed with help from the NGO: Sophia Jimenez, Karmen Perez, Rosa Bustos, and Arelis Jimenes (left to right). Empowered about their right to claim this livelihood, they are actively involved in reforestation and research on mollusc species in the area.

Anita Makri

A board with mollusc species identified. Information gathered by the women goes into a database that now contains data for over 17,000 individuals. “The culture of the research really is based on their work,” says Marvin Fonseca of CoopeSoliDar. “Here they control the process.”

Anita Makri

Aracelly Jimenes Mora, the leader of the association, with member Arelis Jimenes. “This is a joint effort between traditional and scientific knowledge,” says Jimenes Mora. The women told scientists what species to look for, before the scientists could help them single out males and females of the same species.

Anita Makri

The site of a failed reforestation effort. Jimenes says scientists didn’t listen when the women said the nursery was too close to the sea. Now, the site is further inland. They also insisted on a mix of mangrove soil and sand, not the 100 per cent soil experts suggested. “Through trial and error we knew it was better,” she says.

Anita Makri

Mangrove littered with plastic. The trash is picked up twice a month, says Sophia Jimenez, and the women are committed to protecting the area because different species of mangrove support different species of mollusc.

Anita Makri

![A privately owned shrimp aquaculture operation separated by their women’s fishing area by a thin stretch of mangrove. “They don’t give us access [to fishing areas],” says Rosa Bustos. The women say the outfit pollutes the waters, and removing the mangrove has reduced their fishing area.](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/8_Chomes_AM.jpg)

![A privately owned shrimp aquaculture operation separated by their women’s fishing area by a thin stretch of mangrove. “They don’t give us access [to fishing areas],” says Rosa Bustos. The women say the outfit pollutes the waters, and removing the mangrove has reduced their fishing area.](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/8_Chomes_AM.jpg)

![A privately owned shrimp aquaculture operation separated by their women’s fishing area by a thin stretch of mangrove. “They don’t give us access [to fishing areas],” says Rosa Bustos. The women say the outfit pollutes the waters, and removing the mangrove has reduced their fishing area.](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/8_Chomes_AM.jpg)

![A privately owned shrimp aquaculture operation separated by their women’s fishing area by a thin stretch of mangrove. “They don’t give us access [to fishing areas],” says Rosa Bustos. The women say the outfit pollutes the waters, and removing the mangrove has reduced their fishing area.](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/8_Chomes_AM.jpg)

A privately owned shrimp aquaculture operation separated by their women’s fishing area by a thin stretch of mangrove. “They don’t give us access [to fishing areas],” says Rosa Bustos. The women say the outfit pollutes the waters, and removing the mangrove has reduced their fishing area.

Anita Makri

A kitchen space set up by the women’s cooperative. The plan was to open a restaurant for local fishers. It is ready – “but we have a big problem”, says Jimenes Mora: there is no electricity. They say other enterprises have access, but their connection was refused on the grounds of the mangrove being a protected area.

Anita Makri

A photo, part of an exhibition, at the entrance to the kitchen. Gathering molluscs means getting steeped in mud for hours in a day. But it’s the only work available, and CoopeSoliDar says it needs to be dignified. A good day’s harvest is about 400 molluscs, which can fetch 14,000 colones (US$25).

Anita Makri

The idea is to capture knowledge that then feeds into policy discussions. “We really need to generate information that is clear to them [the community], that is simple, that is in their own language, and that they can manage to improve their resources,” says Marvin Fonseca-Borrás, a geographer with CoopeSoliDar.

Back in Barra del Colorado, Fonseca-Borrás is leading a discussion with fishermen and an environment ministry official over a map that captures the community’s knowledge of marine areas and fish species.

“Marine spatial planning techniques are probably the most powerful tool that we have to communicate with fishers,” he says. “It provides information on the biological diversity of the marine ecosystems, but it also gets us to reduce differences between the different actors. And it allows us to find viable solutions to the challenge of combining conservation and development.”

This article was supported by The Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center. For nearly 60 years the Bellagio Center has supported individuals working to improve the lives of poor and vulnerable people globally through its conference and residency programs, and has served as a catalyst for transformative ideas, initiatives, and collaborations.

From November 5 – December 3, 2018, the Bellagio Center will host a special thematic residency on Science for Development, with a cohort of up to 15 scholars, practitioners, and artists whose work is advancing, informing, communicating, or is inspired by the use or design of science and technology to address social and environmental challenges around the world.