07/11/25

Toxic beauty: health risks of Latin America’s cosmetics trade

By: Aleida Rueda

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[MEXICO CITY, LIMA, SciDev.Net] Across Latin America’s cities, a lucrative informal trade in cosmetics and personal hygiene products is thriving.

But, often unbeknown to those who buy them, many of these items are laced with toxic chemicals and heavy metals. They are sold in vast quantities without labels, warnings, or regulation.

Studies reveal the presence of arsenic, mercury, lead and other metals in lipsticks, eyeshadows, nail polish, skin lighteners, and hair products sold cheaply in markets and informal shops.

In downtown Lima, hundreds of people flock daily to the bustling galleries around the historic centre El Cercado to buy cosmetics wholesale and retail, largely ignored by municipal inspectors.

“I come here every month or so to stock up (…) everything is very cheap here,” said Zenobia Urquiza, who runs a market stall in Matucana province.

“I take the opportunity to stock up on some makeup items that sell easily, for example, now that it’s Halloween I’m bringing black eyeshadows, fluorescent eyeshadows, black and bright coloured nail polishes,” she told SciDev.Net.

![During holidays like Halloween, the proliferation of items of dubious origin and poor quality increases. Copyright: Aleida Rueda.]](https://b2242995.smushcdn.com/2242995/wp-content/uploads/maquillaje-salud-2_BODY-756x567.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)

During holidays like Halloween, the proliferation of items of dubious origin and poor quality increases. Copyright: Aleida Rueda.

None of these products have a label, brand, or health certificate identifying their source.

“Do you want quality or price? If you want quality, go buy from Aruma [the largest makeup chain in Peru] or from a catalogue and it will cost you an arm and a leg,” said one vendor.

While regional data is scarce, the informal beauty market represents major losses for businesses. Peru’s Chamber of Commerce reported in 2024 that counterfeit shampoos, fragrances, creams, lipsticks, talcum powder, and nail polish cost the country’s cosmetics industry over US$260 million.

Some, however, profit enormously. “I make about 5,000 soles [about US$1,500] a day just on this stall, sometimes more, sometimes less (…), and in total I have ten stalls,” said the same vendor.

Clandestine laboratories have multiplied, producing cosmetics by hand, often in unsanitary conditions.

Makeup without labels, trademarks, or health registration is sold freely in dozens of shops

in downtown Lima, in the area known as El Cercado. Copyright: Zoraida Portillo.

In July 2025, Peruvian authorities seized nearly two tonnes of counterfeit cosmetics and hygiene products in El Cercado—expired, adulterated, or lacking health registration.

“The worrying thing about this case is that the use of these products made with unknown substances poses a health risk, because their use can cause itching, allergies, hair loss and other more serious health problems,” explained Rumi Cabrera, a specialist from Peru’s Ministry of Health, at the time.

In an article in the journal Frontiers in Public Health, Abdullah M. Alnuqaydan, a researcher at Qassim University, Saudi Arabia specialising in cosmetics toxicity, says toxins can travel into the bloodstream through dermal absorption and pose a real danger to the human body.

A regional problem

The trend seen in Lima is emerging across Latin America, where demand for beauty and personal care products has exploded. The region’s formal market was valued at US$58.71 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach US$95.06 billion by 2034.

Luisa Torres Sánchez, from Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health, believes Latin America is particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of some of these products. “Culturally, we use them more, but also our socioeconomic conditions lead us to choose to sacrifice quality for price,” she told SciDev.Net.

Added to this, products that are banned in other countries, such as pesticides or plastics are allowed to enter Latin America freely due to weak regulations.

In Mexico’s open-air markets, you can find a wide variety of cheap cosmetics and makeup, often sold without any health inspections. Copyright: Aleida Rueda.

Europe, for instance, banned semi-permanent gel nail polishes containing toxic hardeners such as trimethylbenzoyl diphenylphosphine oxide (TPO) and N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine (DMPT) from September this year. These substances remain in wide use in Latin America.

“If they are banned in Europe, could they reach our open-air markets? Perhaps we are receiving the cheapest products with the highest concentration of toxic substances. We don’t know,” Torres warned.

Cancer-causing metals

Researchers are beginning to map the risks. In 2023, as part of her thesis at the National University of San Marcos, Peruvian chemist Evelyn Santos analysed 30 lipsticks from informal Lima markets using atomic absorption spectrophotometry. All contained heavy metals—0.6 ppm of cadmium and 0.2 ppm of mercury on average.

Under US Food and Drug Administration standards, the samples contained permissible amounts of mercury, but cadmium levels exceeded safety limits. By stricter EU standards, most contained heavy metals well above permissible limits.

“What I found in my analysis does not eliminate alarm—lip products that are bought in downtown Lima contain heavy metals, they contain cadmium and mercury,” Santos warned.

“And the presence of heavy metals is very risky, since these metals tend to accumulate in the body and we don’t know what damage this may cause in the future.”

Evelyn Santos (left) analysed 30 lipsticks collected from informal markets in downtown Lima using atomic absorption spectrophotometry. She found heavy metals in all of them. Copyright: Evelyn Santos/SciDev.Net.

Similar findings emerged in Mexico. Researcher Francisco Bautista and his team at the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s Center for Research in Environmental Geography analysed cosmetics sold in Mexican street markets, using spectrophotometry, X-ray fluorescence and scanning electron microscopy.

They found high concentrations of vanadium—a carcinogenic metal—in low- and mid-range lipsticks, “ranging from hundreds […] to thousands”, according to an article published in Mexico’s Journal of Public Health

“Acute vanadium poisoning affects the respiratory and digestive systems and causes heart palpitations, exhaustion, depression and tremors in the fingers and hands,” the article said.

The researchers also detected copper, nickel, tin, lead chlorate, and other minerals, especially in cheaper brands.

“Ideally, heavy metals such as lead, nickel, vanadium and cadmium should not be among the components of lipsticks, as there are no safe concentrations for the human body,” they added.

Eye shadows are another product where dangerous accumulations of potentially hazardous minerals have been detected, especially among the lower-priced ones. Copyright: Aleida Rueda.

Children at risk

Children and teenagers are also increasingly affected. “Schoolgirls buy a lot of makeup because it’s cheap and allows them to be fashionable,” says Peruvian market trader Urquiza.

A study in São Paulo found high arsenic levels in children’s costume makeup, with cancer risks exceeding accepted limits.

Meanwhile, teenagers, influenced by social media, often use products designed for adult skin. Experts warn that this can lead to risks such as hormonal imbalances, allergic reactions, and exposure to chemicals such as parabens, phthalates, sulphates, and formaldehyde.

Bautista explained that so-called “influencers” on social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram have their own makeup brands. In his study, several samples of lipsticks and eyeshadows containing heavy metals came from beauty influencers.

“They don’t even know what they’re selling, but they’re promoting it, and it’s full of heavy metals (…) If I had daughters, I would tell them: ‘Forget about these cheap influencer brands’.”

Long-term threat

Assessing the health impact of these products is challenging because damage develops slowly.

“It’s not easy to study,” said Martha Téllez-Rojo, an epidemiologist at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health. She added: “If I use a deodorant with aluminium today (…) it’s a very slow process.”

Her team has followed 800 women and their children in Mexico City for more than 30 years. In most cases, they found traces of heavy metals in urine and evidence of early neurodevelopmental and hormonal effects, revealing that these substances can be passed from mother to baby.

“I couldn’t say if it’s the deodorant or the cream or the eyeliner, but there are metabolites in their urine associated with effects that we observe from a very early age, very small, that accumulate and affect their neurodevelopment, endocrine system, their sleep patterns or their lipid processing,” Téllez-Rojo explained.

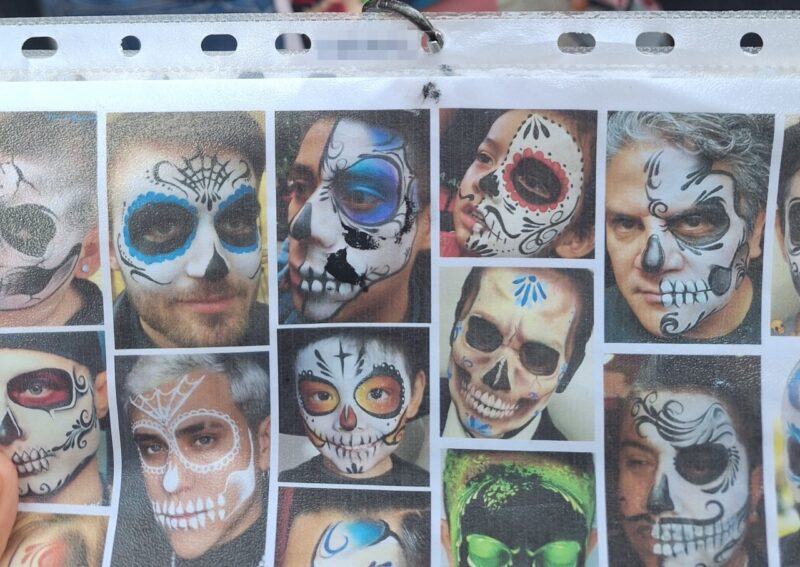

Makeup catalogue. A study in Brazil found heavy metals in metallic-based pigments used by children at various festivities and children’s parties. Image credit: Aleida Rueda.

Nanotechnology specialist Paulina Abrica González, from Mexico’s National Polytechnic Institute, agrees that studying these associations is difficult and time-consuming. She focuses on evaluating the potential harm of nanoparticles used in cosmetics to give skin a smoother appearance.

“I may not wear a lot of makeup, but I do apply it daily (…) And we use it for almost our entire lives, from a young age or childhood, so what we’re going to see are the long-term effects,” she said.

Abrica and her team used animal tests known as comet assays to test titanium oxide nanoparticles found in cosmetics for genotoxicity—the ability of a substance to damage genetic material (DNA) in a cell. This damage can lead to mutations, which may result in diseases such as cancer or birth defects.

Although they found greater DNA damage at higher nanoparticle concentrations, it takes time for the substance to accumulate. Abrica said: “We won’t have results for another five or ten years.”

The researcher warned that this poses a challenge for regulatory bodies which assess—and approve—the safety of cosmetics based on immediate tests that may not be suitable for determining long-term effects. “That’s why we often find out too late that a product is harmful,” she added.

Precautionary principle

Experts agree that the time taken to generate evidence must not delay regulation.

“It’s not that we want to say, ‘Don’t use nanoparticles!’ (…) But we do want to raise awareness about the concentrations, the types of nanoparticles, and the skin types,” Abrica said.

Consumers, she added, deserve transparency about ingredients and concentrations.

![The Lima Chamber of Commerce reported losses of over US$260 million due to counterfeit beauty products in 2024. Copyright: Zoraida Portillo.]](https://b2242995.smushcdn.com/2242995/wp-content/uploads/maquillaje-salud-8_BODY-756x567.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)

The Lima Chamber of Commerce reported losses of over US$260 million due to counterfeit beauty products in 2024. Copyright: Zoraida Portillo.

Torres agreed: “I believe that as consumers we have the right to demand to know what we’re putting into our products. Yes, I’ll buy your cream, but tell me what’s in it.”

Bautista believes that if the risk is particularly high, consumers should be alerted. “That is called the precautionary principle (…) If we applied the precautionary principle, many cosmetic products, lipsticks and eyeshadows would be withdrawn from the market,” he said.

Ultimately, he warned, “We have to stop using these products (…) The use of these products by minors should be strictly prohibited.”

Yet informal sales continue across the region. For many, the choice is economic. As Urquiza, the makeup vendor, put it: “If they had labels they’d be more expensive and we wouldn’t be able to buy them, and poor people also have the right to look good, right?”

SciDev.Net requested comments from health authorities in Mexico and Peru but received no responses ahead of publication.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Latin America and Caribbean desk and edited for brevity and clarity. It featured additional reporting by Zoraida Portillo in Lima. You can read the full investigation in Spanish here.