20/01/26

World enters era of ‘water bankruptcy’, hitting poorest

By: Hadeer Elhadary

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

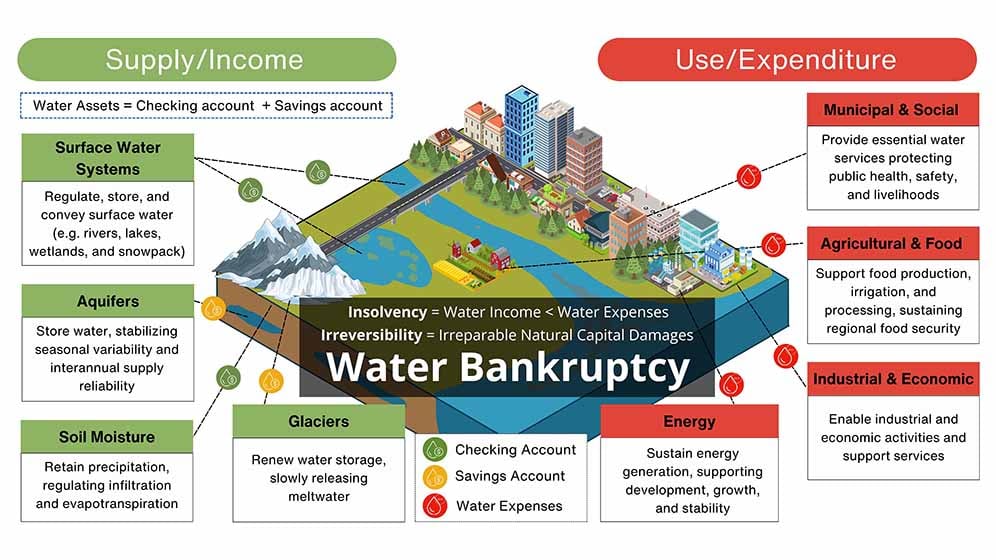

[CAIRO, SciDev.Net] The world has entered an era of “global water bankruptcy,” with water systems in many regions no longer able to recover to their historical levels, according to new report by the United Nations University (UNU).

The report, released today (20 January) is based on a peer-reviewed paper that defines water bankruptcy as the persistent over-withdrawal of surface and groundwater beyond renewable inflows and safe limits, leading to irreversible or prohibitively costly loss of water resources.

It warns that many regions have depleted long-term natural “savings” stored in aquifers, lakes, wetlands, and glaciers, leaving water systems in an irrevocable “state of failure”.

Meanwhile 2.2 billion people lack safe drinking water and nearly 4 billion—almost half the global population—face severe water scarcity for at least one month a year, according to the report by the university’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health (INWEH).

It calls for policy changes that adapt to this new normal, protect the most vulnerable, and prevent further damage, rather than trying to restore lost resources.

“Water bankruptcy happens when both insolvency and irreversibility conditions are present,” Kaveh Madani, the report’s lead author and director of INWEH, told SciDev.Net, citing examples such as long-term groundwater depletion, land subsidence, loss of aquifer or lake storage, and desertification.

“Add weak or fragmented governance, pollution that reduces usable water, and rising demand from agriculture and fast-growing cities, and a crisis becomes a trajectory toward bankruptcy,” he said.

Since the early 1990s, water levels have declined in more than half of the world’s large lakes, which nearly a quarter of the world’s population depend on, according to the Global Water Bankruptcy report.

Around 50 per cent of domestic water and more than 40 per cent of irrigation now come from groundwater, while 70 per cent of major aquifers show long-term decline, it says.

At the same time, about 410 million hectares of natural wetlands—almost equal in size to the European Union—have been erased over the past five decades.

Source: UNU-INWEH

“It is not about one bad drought,” added Madani.

“It is about years of overspending water and degrading the natural capital that produces and stores it—until the system can no longer return to its old baseline.”

On the frontlines

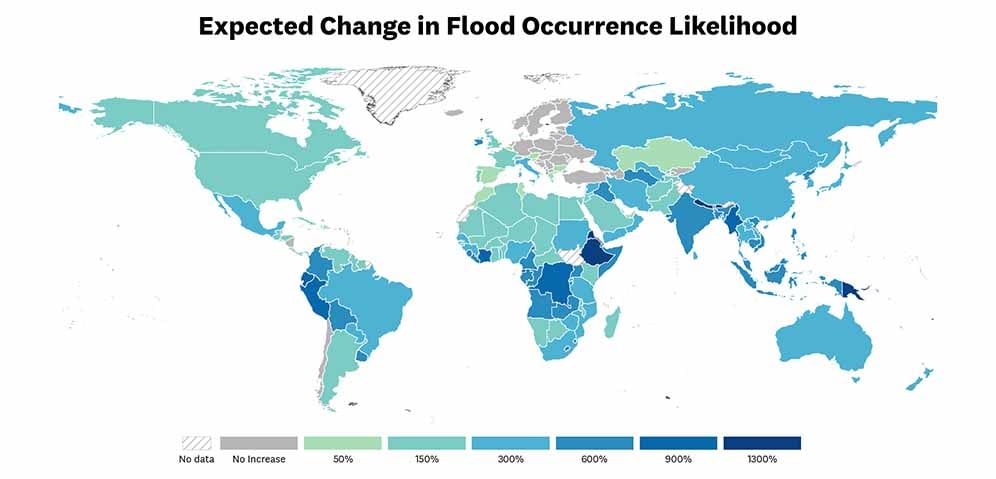

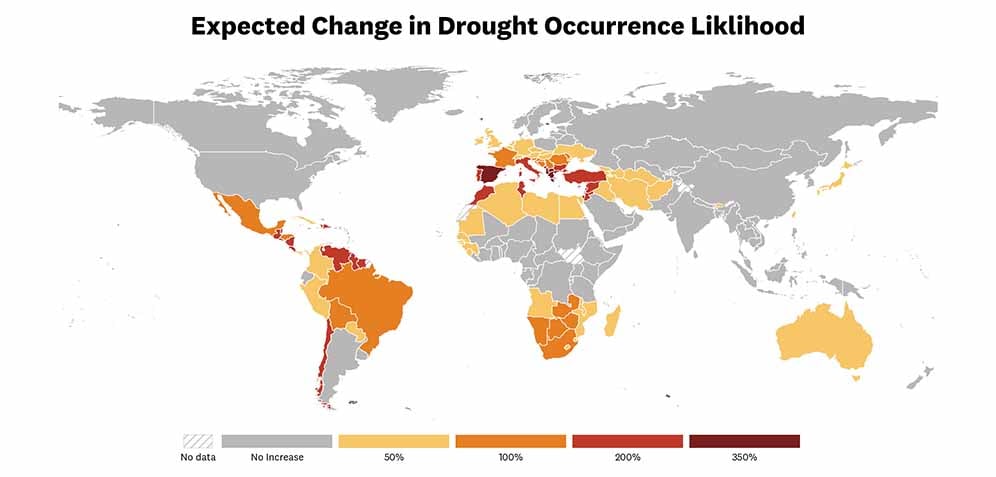

Madani said the most vulnerable hotspots include parts of the Middle East and North Africa, parts of Central and South Asia, northern China, the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, southern Europe and the Mediterranean, southern Africa, and parts of Australia.

Many systems in these regions rely heavily on stressed aquifers and distant water transfers, according to Madani.

“Water bankruptcy shows up in people’s lives as less reliable water, higher costs, and higher risk, unemployment, hunger, forced migration, tension, and even violence,” he said.

He believes policy needs to change from a focus on “restore supply” to “live within limits”.

“Across hotspots, policies reward more use today and delay hard limits,” he explained.

“In many places, this is no longer a temporary ‘crisis,’ but a post-crisis failure.”

Food impacted

The UNU report also warns that global food production is increasingly exposed to water decline and degradation, with more than half of global food production concentrated in areas with declining or unstable water storage.

According to Madani, water shortages in exposed regions can ripple globally, leading to supply shocks, price volatility, and political stress.

When irrigated breadbaskets face groundwater depletion, salinisation, or unreliable surface water, yields can fall, tightening global markets and pushing up food prices, which in turn can deepen poverty and instability.

In this context, Madani stressed the urgent need to reduce water consumption in agriculture without punishing farmers, and to provide “just transition” finance—including income protection, insurance, and alternative livelihood options.

Unequal burden

Fayrouz Eldabbagh, a political science researcher at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), told SciDev.Net: “The era of water bankruptcy is not only a hydrological problem but a deeply political and distributional matter.

“Those hit hardest will be people and areas with the least technical and monetary adaptive capacity to buffer shocks, the weakest political voice, and the highest exposure to water-dependent livelihoods.”

Source: UNU-INWEH

She said poor households in rural areas often face limited water supply, which often means women and girls must travel longer distances to collect water, affecting their schooling and safety.

According to the report, the costs of water bankruptcy fall disproportionately on smallholder farmers, indigenous communities, people living in informal urban settlements and women and children.

Smallholder farmers often lack the resources to adapt to water stress, such as efficient irrigation systems, drought-tolerant seeds, or the ability to switch to less water-intensive crops, explains Eldabbagh.

She says governments need to combine investments in water-use efficiency, irrigation and drainage modernisation, and drought-risk planning with water harvesting and reuse.

Source: UNU-INWEH

Eldabbagh believes that water decisions can be made fairer and more inclusive by connecting water users to policymakers in ways that enhance accountability, participation, and transparency.

Climate resilience

Jauad El Kharraz, CEO and founder of the Water-Energy-Climate Experts Network, says integrated water–energy–climate planning is essential to break the cycle of scarcity and avoid bankruptcy.

“Key strategies include nexus-based policies that consider trade-offs and synergies between water, energy, and climate goals, such as promoting renewable energy that uses less water, or incentivising water-efficient irrigation to reduce energy demand,” he told SciDev.Net.

He also stressed the importance of investing in climate-resilient infrastructure, including storage, groundwater recharge, and treated wastewater, and managing demand through pricing, incentives, and technologies such as AI, big data, and remote sensing to reduce wasteful water and energy consumption.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Global desk.