By: Joshua Howgego

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A simple detector could help conservators at World Heritage sites in the developing world understand and protect against atmospheric pollutants that can damage valuable artefacts.

The pollutant-measuring device has been prototyped by Henoc Agbota, an engineer at University College London, United Kingdom, and presented last week (30 October) at a conference marking the end of a five-year funding programme for heritage science run from the university.

Agbota’s work was prompted by last year's decision by UNESCO (the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) that its World Heritage Committee would begin asking their certified sites to provide yearly figures for atmospheric pollutant levels. In response, Agbota surveyed 25 developing world sites and found that few had the capacity to do this.

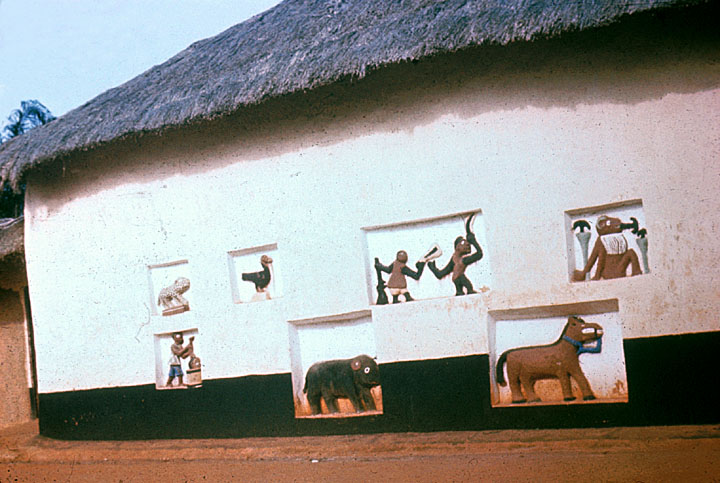

At the Royal Palaces of Abomey, the historical seat of the rulers of the Kingdom of Dahomey in modern-day Benin, conservators care for artefacts such as stone bas-reliefs, wooden thrones and metal weapons. Urbain Hadonou, one of the conservators, tells SciDev.Net that he runs a project called museum school through which local cultural researchers come to study the artefacts.

But such projects could be at risk unless artefacts are protected from harmful pollution.

Almost three-quarters of the respondents to Agbota’s survey reported observing damage to objects that they attributed to pollution. This took the form of particle deposits, corrosion and the formation of ‘black crusts’ on artefacts.

Agbota hopes his device will help to avoid this damage.

“We need something that not only identifies levels of pollution, but also uses techniques to effectively protect the artefacts.”

Urbain Hadonou, Royal Palaces of Abomey

His instrument consists of a series of so called piezoelectric quartz crystals — which generate electric currents as they expand or contact by minute amounts — coated with varying thicknesses of copper, iron, nickel or tin. As pollutants absorb to these metallic surfaces, they change the crystals’ mass, altering the electrical output and allowing pollution levels to be calculated.

The prototype can detect oxides of sulphur and nitrogen, ozone and humidity — all of which can accelerate artefact degradation.

Agbota says the hardware needed to build the detector costs less than £400 (about US$640) and he hopes it could be produced cheaply at scale. He notes that the nearest competitor on the market, the OnGuard 3000, manufactured by US firm Purafil, costs much more.

Agbota’s device was tested at several heritage sites in developing nations, including the Abomey Palaces, and has had good feedback. As a result, he says, “one site in Kenya actually decided to move part of their collection to a less-polluted location”.

Demand — but little supply

Agbota says more research into solutions for developing-world conservators is needed, but that it is hard to find funding for it or interested researchers. “There’s a lot of demand on the side of the conservators in the developing world, but on the research side it’s thinner.”

Hadonou agrees that there is a need for better pollution monitoring tools, but adds that “we need something that not only identifies levels of pollution, but also uses techniques to effectively protect the artefacts”.

Agbota sees his project as a way of showing that pollution is a real concern for conservators at World Heritage sites. Being armed with this knowledge could help heritage conservators to lobby for more resources.

“All of the people I’ve met in the conservation business in the developing world are looking for evidence so they can take it to decision-makers,” he says. “This project may get us some of the way there.”

Additional reporting by Amzath Fassassi.

References

Studies in Conservation, doi 10.1179/2047058413Y.0000000083 (2013)