By: Paula Park

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

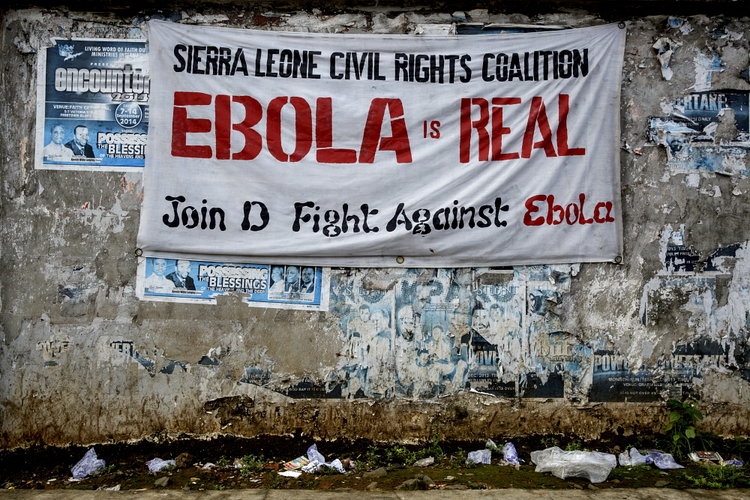

Payment delays caused by an inefficient global alert system for health crises have hampered the world’s response to Ebola.

An analysis, published in the British Medical Journal on 3 February, found that only about a third of the aid money pledged to tackle the Ebola outbreak in West Africa has been paid out.

The WHO declared the Ebola outbreak as an international health emergency in August 2014, nearly five months after Guinea had notified the organisation of an Ebola outbreak. By that time, an estimated 1,500 people had died, according to the WHO.

Karen Grépin, the study’s author and a global health policy researcher at New York University, found that it was not until this official declaration that a large-scale worldwide funding campaign began (see graph).

The consensus appears to be that at least US$1.5 billion is needed in total to beat the Ebola outbreak, according to the analysis. But by the end of 2014, donors had paid just US$1.09 billion of the US$2.89 billion they had previously pledged to affected countries, it says.

“Having access to these funds earlier would be a big part of a new mechanism,” says Grépin. “To rapidly deploy resources and keep any type of public health emergency in check would be a great start.”

To achieve this, the distribution of funding to tackle large-scale disease outbreaks should be improved to prevent future delays, the analysis states. Extra funding pots that can be deployed quickly and without bureaucratic hassle in emergencies would also help, says Grépin.

A more efficient alert mechanism would enable the WHO to declare emergencies faster, Grépin says. But creating this would be difficult, as such a declaration can only be made through consensus among countries, which takes time, the study found. The WHO’s emergency declaration, for example, was only possible after it had conferred with every West African government.

Marta Tufet, who coordinates research collaboration between African countries and the Wellcome Trust, a UK medical charity, says the WHO’s structure, where each decision needs to be adopted by all member states, stops it from acting more efficiently.

“Although some reforms [to decision-making processes] are proposed, implementing those reforms will take some time as well,” she says. These reforms were promised in 2005 after the outbreak of SARS, Tufet says.

In the fallout from this severe viral infection of the lungs that spread across Asia in 2003, the WHO and its member countries revised their health regulations to broaden the definition of what constitutes an international health crisis to include problems with response coordination. They also created specific deadlines for all WHO member countries to report national health emergencies, according to the type of health hazards expected and governmental preparedness.

With Ebola, West African countries followed through on their promise by notifying the WHO promptly and accurately, says Tufet. Grépin’s analysis shows that WHO medical staff and experts were in constant contact with Guinea, local leaders and medical staff by 23 March 2014.

The WHO was unavailable for comment. But on 25 January, the organisation’s director-general, Margaret Chan, recommended in a report to the WHO’s executive board that it hasten future responses to international health crises.

In addition to improving nations’ abilities to control disease, the WHO must strengthen its emergency response management, Chan said.

> Link to the analysis in the British Medical Journal

> Link to Chan’s Ebola report to the WHO executive board