09/11/21

COP26: Rich nations ‘resisting paying for climate loss’

By: Fiona Broom

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Urgent steps must be taken to change the “toxic” tone of negotiations relating to the irreversible impacts of climate change, science and civil society leaders have told political leaders at COP26.

Delegates say wealthy countries have been digging in their heels against calls from climate-impacted countries for financial support to both avoid and address loss and damage.

The term ‘loss and damage’ relates to irreversible climate change impacts that can no longer be adapted to or mitigated against, usually associated with extreme weather events such as floods, droughts and wildfires.

“Unfortunately, negotiations get stuck in toxic issues of liability and compensation. We need to think about humanity. That’s what we’re asking for here and we’re not getting much in return.”

Saleemul Huq, director, International Centre for Climate Change and Development, Bangladesh

Non-government climate leaders have said that climate finance, particularly for loss and damage, is among the most important issues for developing countries to be discussed at the climate summit.

But some say that the space to thrash out the problem has been restricted, with loss and damage talks being pushed to the sidelines.

Hundreds of people crowded the halls within the COP26 Blue Zone on Monday in an effort to join a loss and damage meeting hosted by the COP presidency and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, but many were turned away when the room reached capacity.

Saleemul Huq, the director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) in Bangladesh, said loss and damage talks needed to appeal to the hearts and humanity of negotiators.

“Unfortunately, negotiations get stuck in toxic issues of liability and compensation,” Huq told the presidency meeting. “We need to think about humanity. That’s what we’re asking for here and we’re not getting much in return.”

Scotland’s government last week pledged £1 million (US$1.36 million) for loss and damage, supporting a partnership with the US-based Climate Justice Resilience Fund to help communities rebuild from climate-related events.

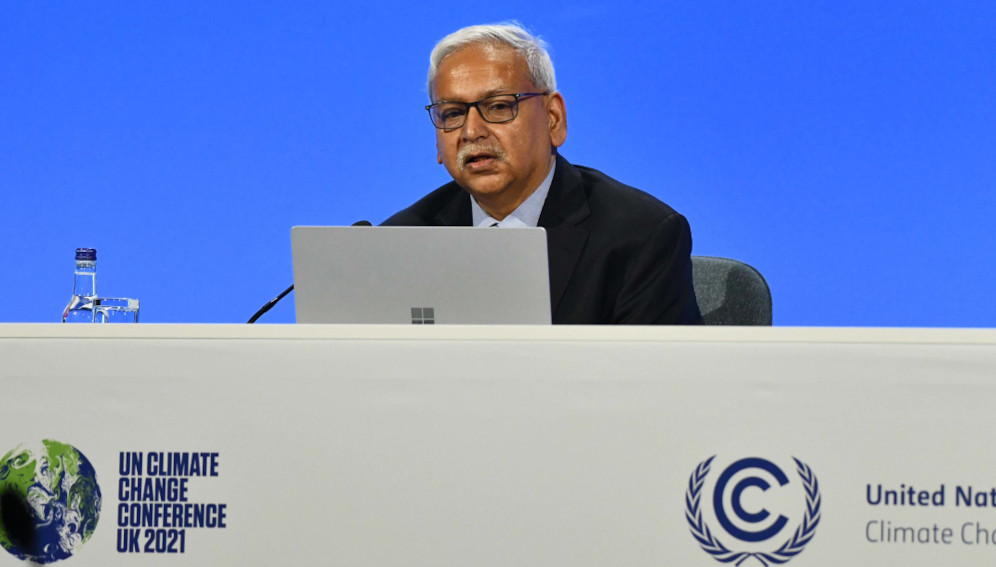

Saleemul Huq speaks at the Building a Climate Resilient Future event at COP26 on 8 November at the SEC conference venue, in Glasgow. Copyright: Justin Goff/UK Government, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

While that figure is small, it could be “the drop that starts the rain”, according to James Bhagwan, general secretary of the Pacific Conference of Churches.

Twelve years ago, at the UN climate summit in Copenhagen, developed countries agreed to mobilise $100 billion a year in climate finance by 2020 – a pledge which has not yet been fulfilled.

Sven Harmeling, global policy lead on climate change and resilience at CARE International, believes that developing countries are being “silenced” by wealthy countries who resisted calls to discuss loss and damage finance.

“We think that is absolutely inappropriate,” Harmeling said. “When the developed countries promised the US$100 billion, that was for adaptation and mitigation. It was at a time – 2009 – when basically no one talked about loss and damage.

“We also argue there’s an additional need for finance to address loss and damage. Developed countries don’t like that idea and they also don’t like the idea of a separate stream of finance. I think there are ways in practice where adaptation, and loss and damage actions, can be integrated, but they are still not the same.”

Mohamed Adow, director of the energy and climate think-tank Power Shift Africa, said loss and damage talks often left out the issue of finance, to avoid discussions of legal liability and compensation. But he said that negotiations had gone beyond the issue of compensation, and there were many ways that support could be provided without assuming liability.

Maria Laura Rojas Vellejo, executive director of Colombian non-profit climate group Transforma, said that the quality of financial support available for loss and damage would be crucial.

“What I mean by quality is, how are the resources that are available for climate finance made available to developing countries?” Rojas Vellejo said. “The problem with this is that many of [the resources] are available in the form of loans, which increases countries’ public debt. This should not be the case.”

She said ‘concessional loans’ — those that have below-market interest rates or longer repayment periods — and grants should be made available, rather than commercial and private loans alone.

At the most recent climate summit, Madrid’s COP25 in 2019, the Santiago Network was established to avert, minimise and address loss and damage by catalysing technical assistance for climate-vulnerable developing countries.

“So far, [the Santiago Network] has only been a website where a few organisations have signed up,” said Harmeling. “There’s no secretariat capacity yet, the functions have been very broad. It’s important to make clear the next steps.

“As an interim measure there needs to be a clearly dedicated secretariat with financial support. I hope we’ll get to this by the end of this COP.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Global desk.