07/07/20

Planning for the next pandemic: facts and figures

By: Gareth Willmer

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Influenza, coronavirus, obesity: Is the world ready for the next pandemic?

Mere months before COVID-19 hit, an international group of scientists warned that the world faced the “very real threat” of a pandemic from a respiratory pathogen causing 50 to 80 million deaths.

“A global pandemic on that scale would be catastrophic… The world is not prepared,” said the report by the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB), a body co-convened by the World Bank and World Health Organization (WHO).

Though deaths from COVID-19 are currently a long way off those numbers — just more than 550,000, as of July — it provides a stark warning for the future in our increasingly connected societies. Factors including increased travel and rapid population growth in places with weak health systems are contributing to the rising risk.

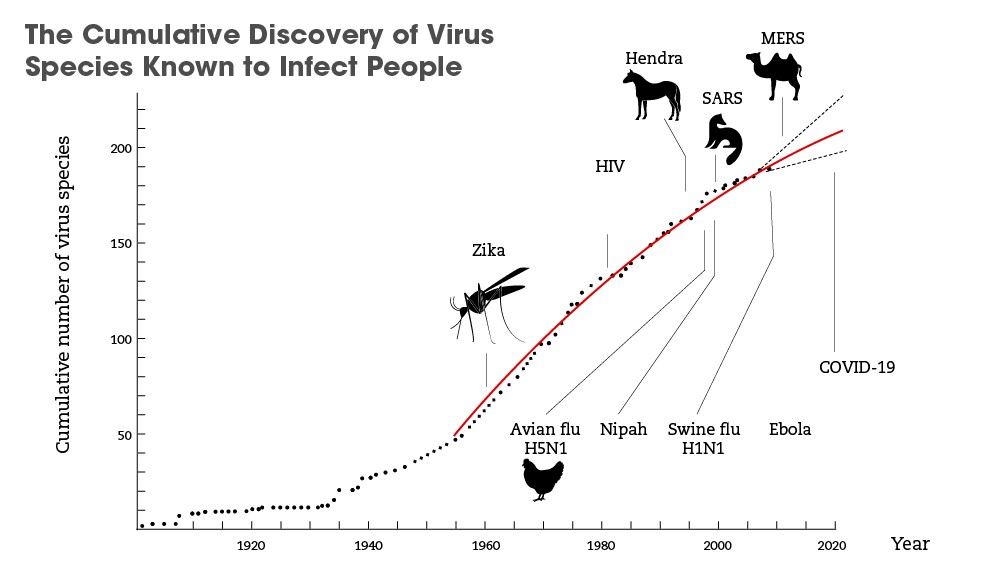

With the WHO tracking almost 1500 epidemic events in 172 countries between 2011 and 2018, the GPMB said diseases such as influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Ebola and Zika were “harbingers” of a new era of high-impact, harder-to-manage outbreaks.

And infectious disease outbreaks are increasing in both variety and number, up from fewer than 1000 in 1980 to more than 3000 by 2010. In the past decade, aside from COVID-19, the WHO has designated five other disease outbreaks as a “public health emergency of international concern” — Ebola twice, swine flu, poliovirus and Zika.

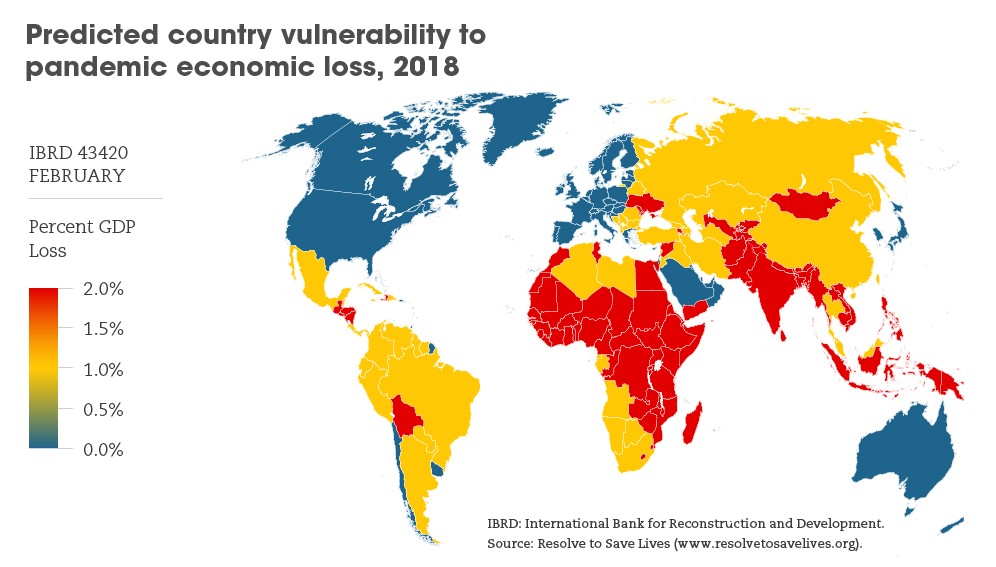

Unsurprisingly, disease outbreaks threaten a far heavier impact on lower-resourced communities with limited access to basic health services, clean water and sanitation, as well as poor infrastructure and governance, says the GPMB.

Meanwhile, an Epidemic Preparedness Index cited in a study in BMJ Global Health last year found that the least-prepared countries were concentrated in Central and West Africa and South Asia — with a “potentially dangerous mismatch” between the onset of infectious diseases and capacity for detection and mitigation.

Zoonoses and the resistance crisis

Scientists fear that urban growth and human disturbances to ecosystems will increase the incidence of infectious and zoonotic diseases — those that cross the boundary between animals and people.

Some 2.5 billion more people are expected to move into cities by 2050, with Asia and Africa accounting for 90 per cent of growth, while numbers of slum dwellers reached more than one billion globally in 2018.

According to the World Wide Fund For Nature, three or four new zoonotic diseases are emerging each year, and the problem is likely to worsen because of the need to feed a growing population and demand for wild meat as both a necessity and delicacy.

The WWF notes that hunting and butchering of bats and chimpanzees have been cited as potential sources of the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

Exacerbating the threat of outbreaks is the growing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, making diseases harder to treat. This is compounded by a worrying shortfall in research and development to confront the crisis, according to reports. Ninety per cent of future AMR-related deaths are predicted to occur in Africa and Asia over the coming years, while the United Nations forecasts that global fatalities may swell from 700,000 a year now to 10 million by 2050 if effective solutions are not found.

On the other hand, the WHO has just reported a significant step forward: a huge surge in the number of countries now monitoring and reporting on AMR. Its surveillance system aggregates data from 64,000 sites worldwide, up from 729 in two years.

Economic impacts

The COVID-19 outbreak has underlined that the direct effects of epidemics on health are far from the only issue, as the pandemic has hit economies hard and pushed people towards poverty.

“The pandemic is reversing the trend of poverty reduction,” said a recent report by the UN Secretary-General on progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. It estimated that 40 to 60 million people would be pushed back into extreme poverty this year, the first global increase in poverty in two decades.

An earlier UN report predicted that 56 per cent of those slipping into extreme poverty in 2020 would be in Africa, while the UN’s World Food Programme estimates that 130 million more people in low- and middle-income countries may be confronted with acute food insecurity this year.

Other crises have also borne out the costs: West Africa’s Ebola outbreak is estimated to have caused losses of US$2.2 billion in gross domestic product in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2015. According to the GPMB, the 20 per cent fall in Sierra Leone was enough to wipe out five years of development.

Question of nutrition

And the world is facing not only risks from infectious diseases, but also non-communicable conditions because of changes in lifestyle and urbanisation.

The incidence of obesity has tripled globally since 1975, according to the WHO, and has been on an upward trajectory in regions where the rate was previously low. In Africa, the number of overweight children aged below five is estimated to have grown 24 per cent since 2000, while nearly half of overweight or obese children of those ages resided in Asia in 2019.

In addition, lower-income countries are increasingly seeing a “double burden” of undernutrition and obesity within the same communities, in the same families and even in some individuals, who may be both stunted and overweight. A recent report in The Lancet estimated that more than one third of low- and middle-income countries experienced these overlapping effects — driven by rising exposure to low-quality, ultra-processed food and drinks.

In relation to diseases, there is another side to the food story too: changes to the environment and societies pose a disease threat to crops as well as people. Ten to 40 per cent of staple crop yields are estimated to be lost to pathogens and pests and climate change may heighten losses in the coming years.

Last year, a strain of Fusarium wilt disease that has plagued banana plantations in parts of Asia for decades spread to Latin America — a region estimated to account for 80 per cent of global banana shipments. Dubbed “banana COVID” by some, the disease has no known cure.

And pressure looks set to grow to contain crop diseases, amid the world’s growing population and a rise in the number of people facing food insecurity from 23 per cent in 2014 to 26 per cent in 2018, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

Mitigation outlook

Yet it may not all be doom and gloom if the right steps can be taken. As the world scrambles to find a vaccine for COVID-19, there has been some reflection on previous vaccine successes. Smallpox has been eradicated, cholera cases fell 60 per cent in 2018 and wild polio cases have declined more than 99 per cent in the past 30 years — though some polio immunisation programmes face operational challenges and vaccine-derived polio is on the rise.

Progress on universal healthcare has been fastest in lower-income countries, as improvements in quality and access since 2000 have led to reductions in child and maternal deaths. However, the poorest countries still lag far behind and improvements have slowed in these countries since 2010.Increasingly sophisticated technological tools are also helping battle the variety of diseases the world faces. Artificial intelligence is being used to monitor Fusarium wilt while gridded population maps are helping identify areas at risk of disease outbreak and spread.

There is hope, too, that falling levels of pollution during lockdowns will focus minds on creating healthier, more sustainable environments. But there is a lot to consider if the world is to learn from the lessons of COVID-19 and be better prepared whenever the next pandemic hits.