06/07/19

Antimicrobial resistance: facts and figures

By: Inga Vesper

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

If unchecked, antimicrobial resistance could become deadlier than diabetes, TB and HIV/AIDS combined, writes Inga Vesper.

What do you think is the most dangerous disease on the planet? Heart disease, respiratory problems and tuberculosis haunt citizens of developing countries. But while treatment for these diseases is increasingly available – resulting in falling fatalities for all three – there is another, lesser known threat that is growing every year.

Already, more than 700,000 people around the world die annually from diseases caused by bacteria that have developed antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The World Health Organization estimates that if current trends continue, the problem could kill 10 million people every year by 2050, making antimicrobial resistance more dangerous than diabetes, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS combined.

This problem will hit developing countries particularly hard. Infections can be contracted by anyone anywhere, simply by being exposed to dangerous bacteria. But those with the least reliable sanitation, the most polluted water and the worst access to simple medical interventions, such as antibiotic wipes, will carry the biggest burden.

These are not just dire projections. Around 200,000 newborns die every year because they catch infections that simply do not respond to drugs. Research on this is patchy, but according to the WHO, around 40 per cent of infections contracted by newborn babies resist available treatments. The vast majority of resulting deaths occur in developing countries.

The economic toll of AMR

Surviving an antibiotic resistant infection also has its costs. If no immediate treatment is available, patients may have to try alternative medicines in the hope that their infection will respond. Instead of one course of antibiotics, two, three or even four may be needed, placing financial pressures on patients, families and local health systems. These extra costs could reach $1 trillion per year by 2050, the World Bank warns.

Because of this, the World Bank estimates that low-income countries could lose up to five per cent of their GDP in the same time frame – making the financial impact of antimicrobial resistance worse than that of the 2008 financial crisis. More than 25 million people in the poorest nations could be pushed into extreme poverty, the bank said in a 2016 landmark report.

Considering these high costs, the financial outlay required to combat antibiotic resistance seems small. Kevin Outterson, a law researcher at the University of Boston, estimates that the total cost of eradicating antimicrobial resistance would be around $10 billion. That’s about as much money as member states of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change commit each year to the Green Climate Fund.

What’s causing resistance?

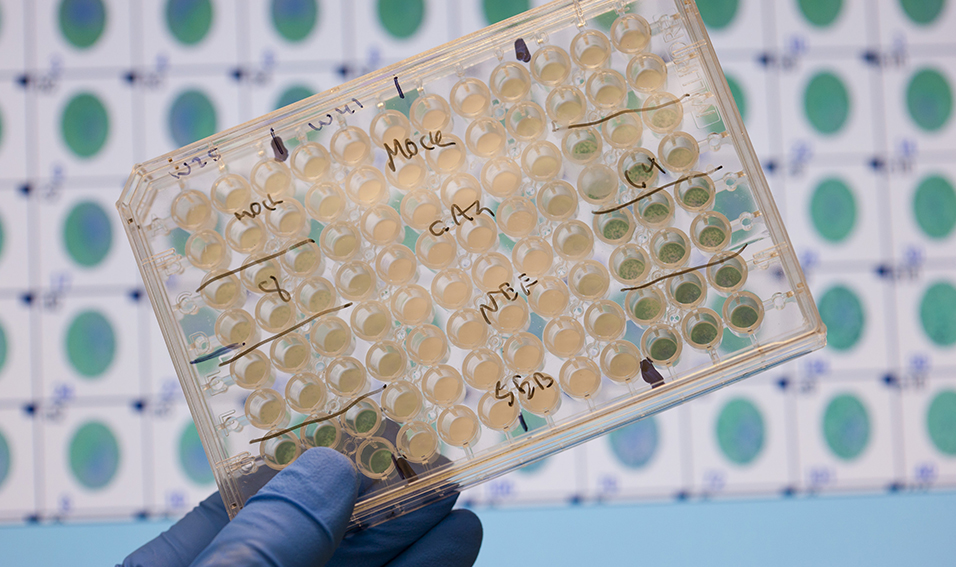

So what is halting progress on this global crisis? First of all, antimicrobial resistance is a complex problem. Bacteria are constantly evolving, and it is difficult to track which ones have become resistant. Among the most dangerous ones are Staphylococcus Aureus, also known as the hospital bug MRSA, Neisseria Gonorrhoeae, which causes the sexual disease gonorrhoea, and E. coli, the cause of diarrhoeal diseases.

Unfortunately, developing countries are as much a cause of the problem as they are victims. To be effective, antibiotic drugs need to be taken regularly and for a full cycle, usually ranging from one to six weeks. But in places where drugs are expensive or not readily available, many patients will interrupt these drug cycles as soon as they feel better and save remaining tablets for later use.

Overprescription is also a problem. In areas where bacterial diseases such as diarrhoea and throat infections are common, doctors will often prescribe antibiotics without proper diagnosis or as a precaution, fuelling overuse.

In addition, prophylactic use of antibiotics is common in farm animals. While the European Union banned certain antibiotics in livestock rearing in 1997 and 1999, their use to maintain the health of cattle in developing countries continues unabated.

What’s being done?

To make matters worse, new antibiotics are expensive to develop – R&D costs alone can easily reach $300 million per drug , to which a company must add another $3-4 million for approval fees, a UK-commissioned review on AMR found in 2015. However, due to strict international regulation, the cost of the drugs is kept low, making development less profitable and therefore unappealing to pharmaceutical companies.

Fortunately, governments, companies and international bodies are increasingly aware of the need for action on antimicrobial resistance. In 2016, more than 100 companies teamed up to form the AMR Industry Alliance. They submitted a report on problems related to the cost of antimicrobial resistance to the World Economic Forum in Davos. In their declaration, the companies said they are already spending close to $2 billion a year on developing new antibiotic drugs. However, they also called on governments to help fund economically risky research and tackle problems such as overprescription and inappropriate use through better regulation.

While better control of the use of antibiotics is crucial to tackling antimicrobial resistance, experts stress that access to these drugs must be widened, not curtailed. Around 6 million people die every year of sepsis in developing countries because they have no access to antibiotic drugs – ten times as many as those who die of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The most famous – and still most widely used – antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered in 1928 by Alexander Fleming. Aware of the millions of lives it would save, Fleming donated the formula to the world for free. Now, nearly 100 years later, the challenge is how to preserve this gift, to save many millions more.