20/07/16

Ancient parasite remains a modern scourge

A sand fly feeding on human blood. The bite of infected female sand flies is responsible for transmitting the parasite that causes leishmaniasis

Jon Spaull

A girl at a clinic in Kabul, Afghanistan, with lesions on her face caused by cutaneous leishmaniasis. Exposed skin is more vulnerable to sand fly bites

WHO/Christopher Black

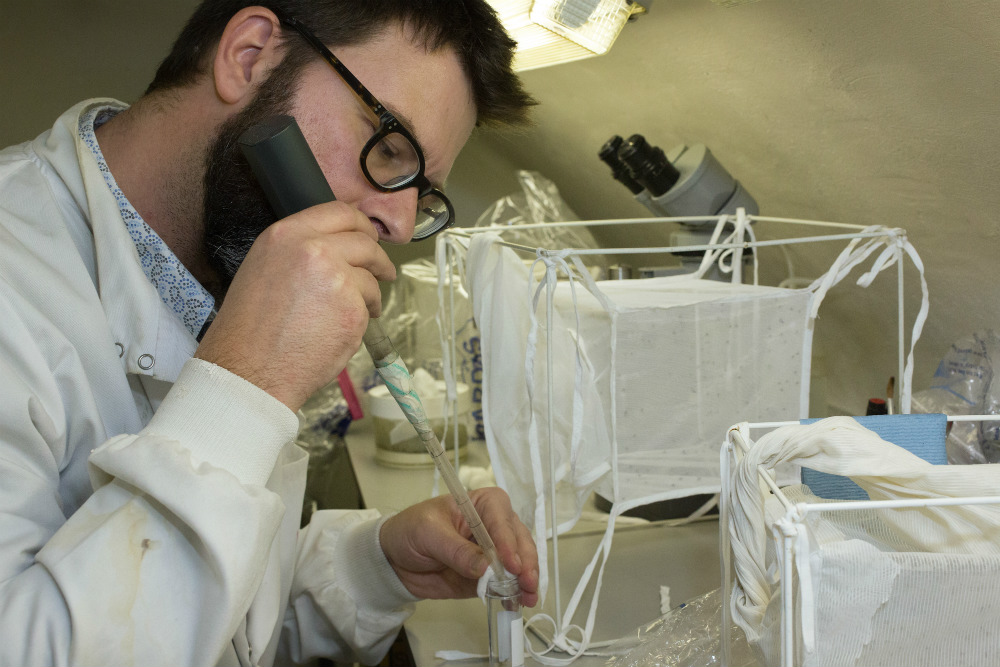

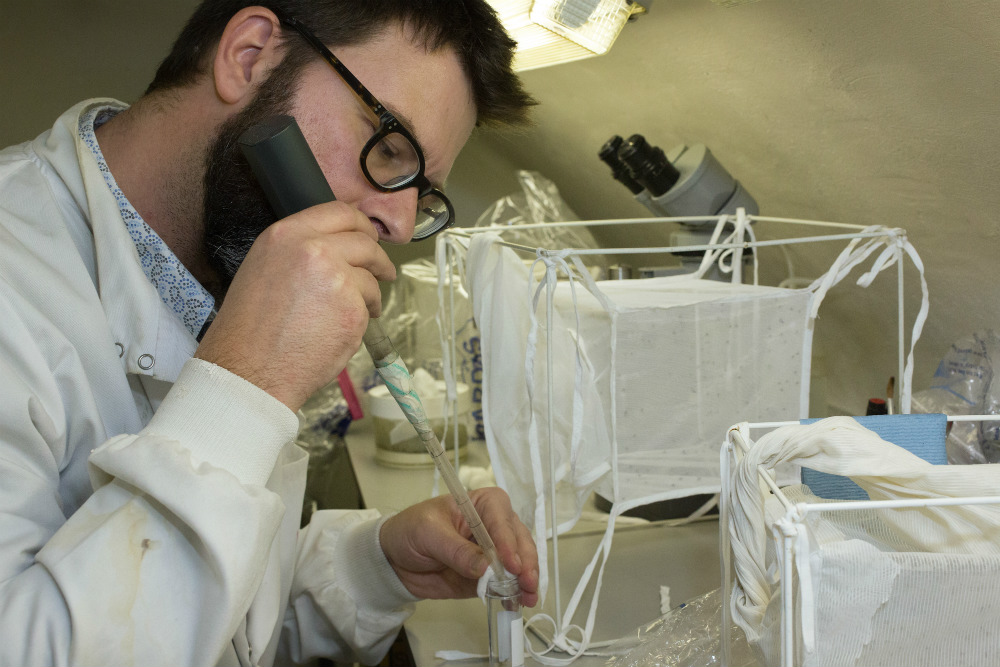

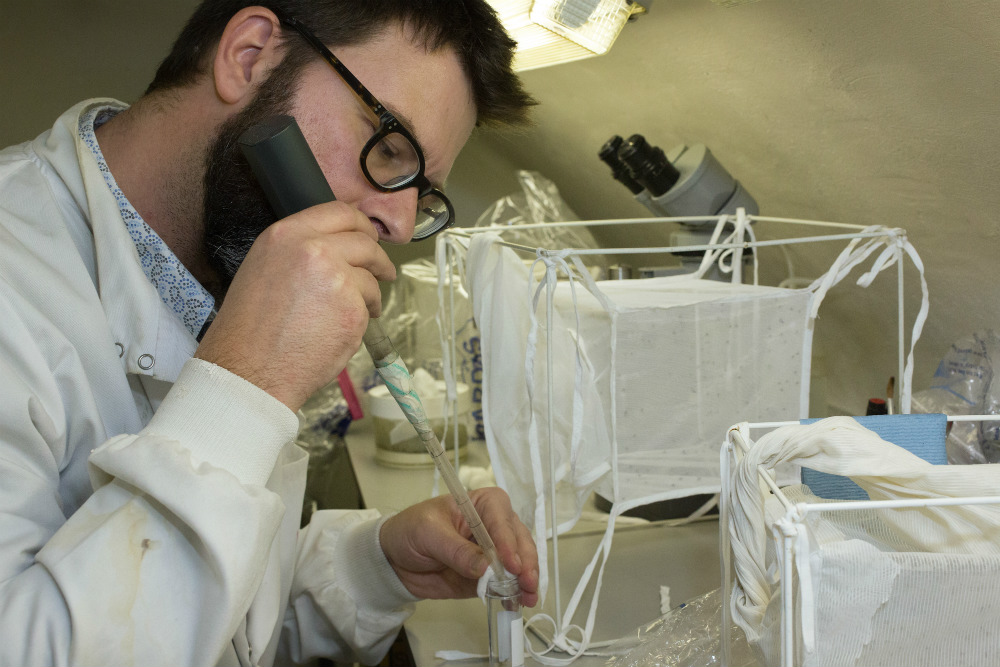

Researcher Matthew Rogers examines the leishmania parasite in his lab at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) in the United Kingdom

Jon Spaull

Rogers places sand flies taken from a large colony in the lab into a glass tube

Rogers puts the tube of uninfected sand flies on his hand to blood feed

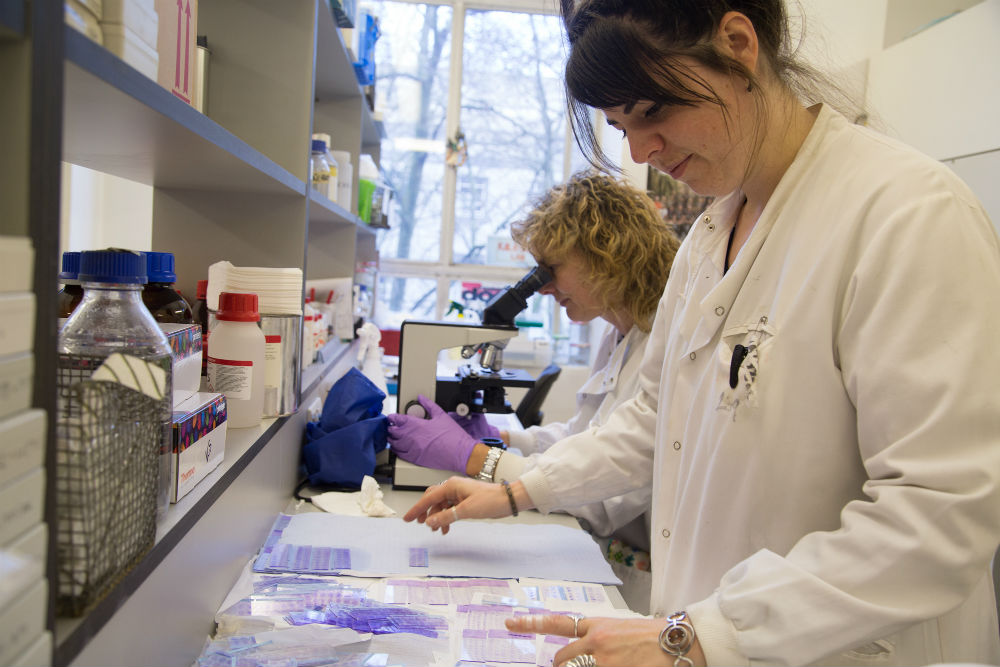

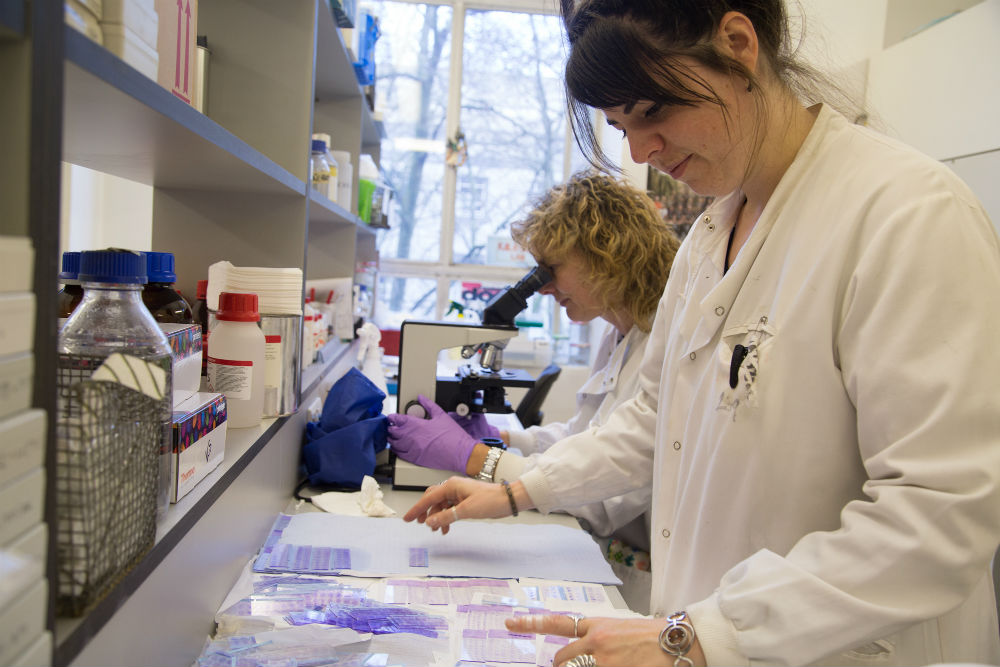

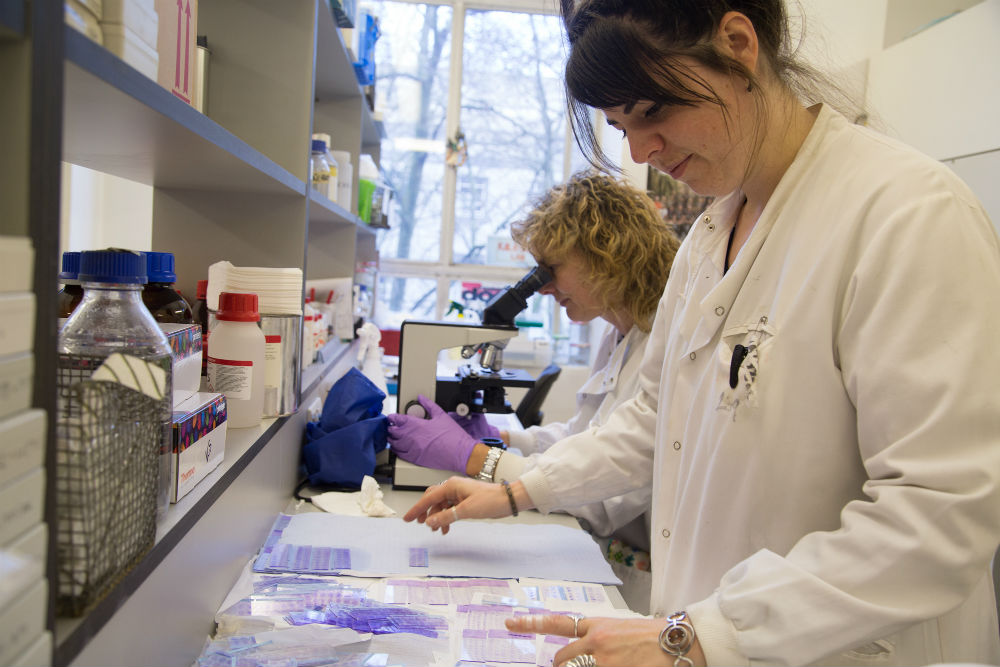

Researchers Katrien Vanbocxlaer (at the front) and Vanessa Yardley examine slides of smears from mouse liver and spleen in a LSHTM lab. These are the organs that are infected by visceral leishmaniasis

Jon Spaull

Rows of slides of smears from mouse liver and spleen. The slides are used to determine the extent of visceral leishmaniasis infection

Jon Spaull

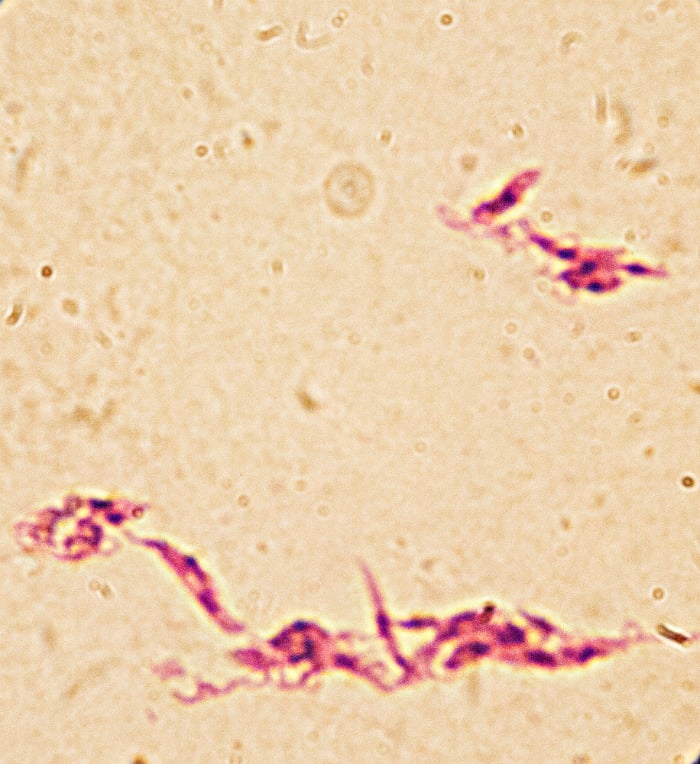

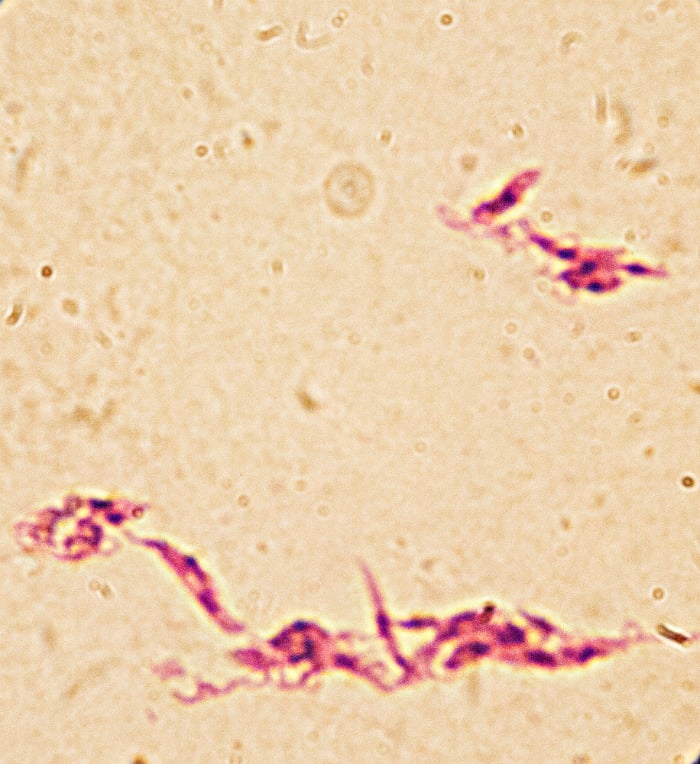

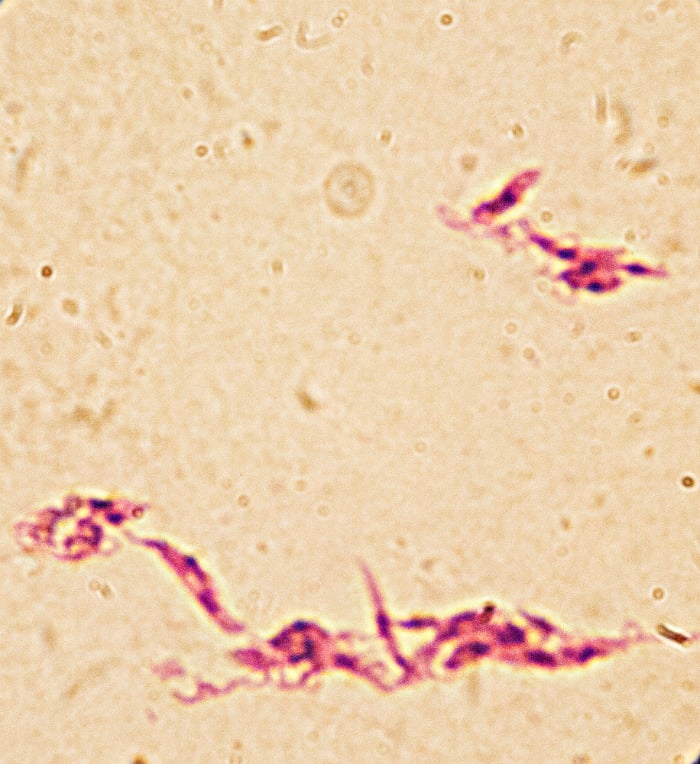

Microscope image of the leishmania parasite (purple). At this stage of its life cycle, it is known as a promastigote. The parasite develops into this form in the sand fly and is then transmitted through bites

Jon Spaull

![Katrien Vanbocxlaer testing the release of a [potential?] drug using devices called Franz cells. The cells have two chambers separated by a membrane of mouse skin, to model the drug’s application to skin. The drug is put in the top chamber and samples taken from the bottom one to see how much of the drug has passed through](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/09leish.jpg)

![Katrien Vanbocxlaer testing the release of a [potential?] drug using devices called Franz cells. The cells have two chambers separated by a membrane of mouse skin, to model the drug’s application to skin. The drug is put in the top chamber and samples taken from the bottom one to see how much of the drug has passed through](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/09leish.jpg)

![Katrien Vanbocxlaer testing the release of a [potential?] drug using devices called Franz cells. The cells have two chambers separated by a membrane of mouse skin, to model the drug’s application to skin. The drug is put in the top chamber and samples taken from the bottom one to see how much of the drug has passed through](https://www.scidev.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/09leish.jpg)

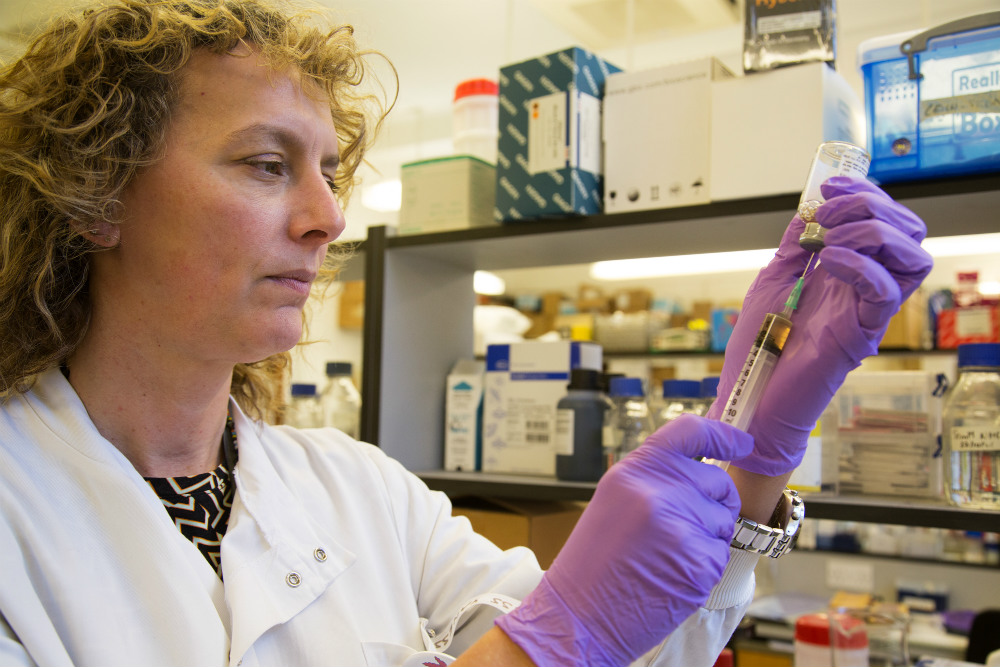

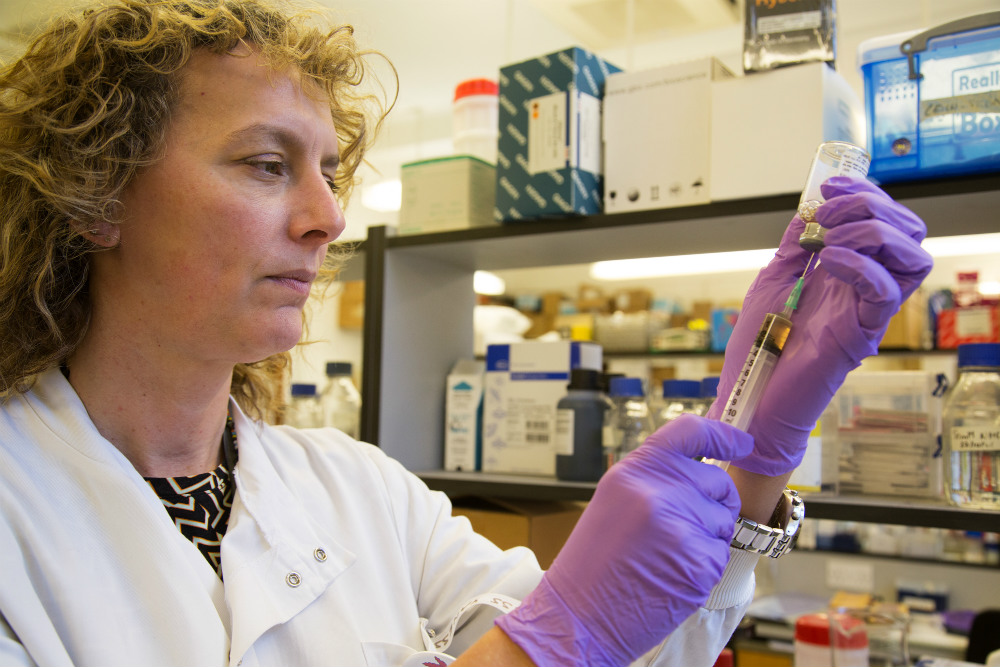

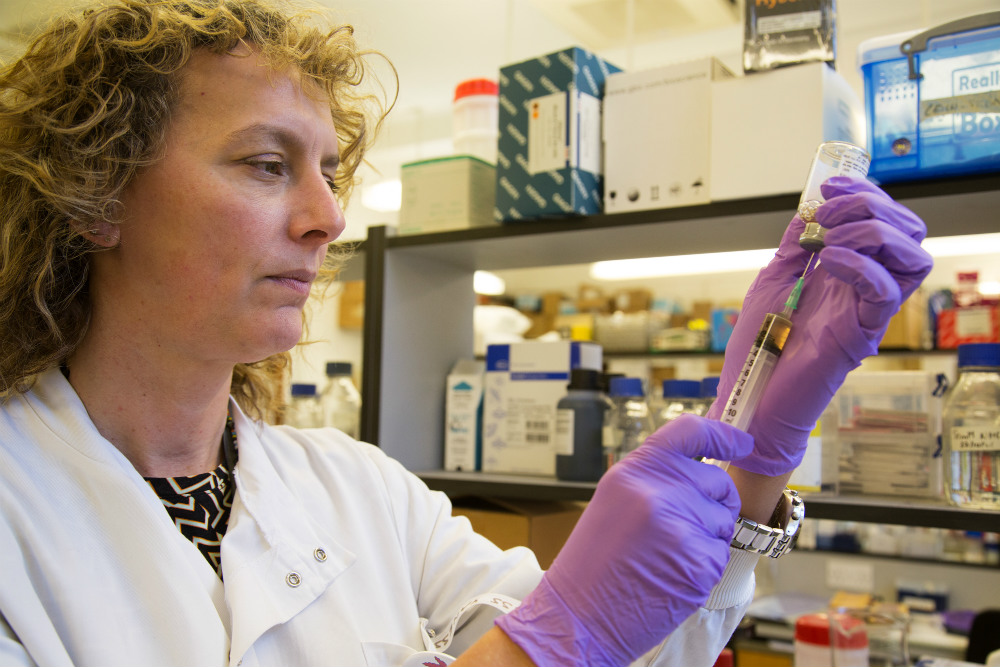

Katrien Vanbocxlaer testing the release of a [potential?] drug using devices called Franz cells. The cells have two chambers separated by a membrane of mouse skin, to model the drug’s application to skin. The drug is put in the top chamber and samples taken from the bottom one to see how much of the drug has passed through

Jon Spaull

Close up of a Franz cell. The researchers use mouse skin as they will be later testing the drug on live mice. They also use human skin sourced from stomach and breast reduction surgeries

Jon Spaull

Vanessa Yardley removes the drug AmBisome from a vial. The drug is used to treat leishmaniasis

Jon Spaull

By: Jon Spaull

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Leishmaniasis is a disfiguring and potentially deadly neglected tropical disease that affects more than one million people in 98 countries worldwide. It is caused when the leishmania parasite is transmitted by sand fly bites.

This photo gallery looks at the work of researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the United Kingdom into preventing the transmission of leishmaniasis and finding better drugs to treat the condition, with milder side effects than the current available.

Leishmaniasis is a disease of the poor: those living in basic conditions with limited sanitation and those who sleep in the open are most likely to get bitten. Manual labourers working outdoors are also more exposed to sand flies.

The disease is widespread in the tropics and subtropics in Latin America, North and East Africa, the Middle East, India, China and South-East Asia. It is increasingly being seen in temperate climates as it moves north into Greece, Italy and France. This might be one reason why funds to research the disease have risen in recent years.

There are three main forms of the disease: cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral, with this last form killing an estimated 20,000 people every year.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis often causes disfiguring scars, which can lead to those infected being banished from communities who mistakenly fear the disease is infectious.

Matthew Rogers of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine is researching the transmission biology between the leishmania parasite and the sand fly. The female sand fly needs blood to make eggs. When the insect feasts on infected blood, the parasites enter the fly’s gut and create a gel. This gel hampers the fly’s ability to feed, meaning it has to feed more often and from more hosts. At the end of feeding, the fly regurgitates part of the parasite-containing gel into the bite.

The leishmania parasite may have been around for 65 million years. Rogers says this means it has had millions of years to evolve the perfect the process of transmission.

Vanessa Yardley and Katrien Vanbocxlaer are researching leishmaniasis drugs. Currently they are at the early stages of preclinical drug discovery tests for a novel compound designed to penetrate and remain active in the lower layer of the skin long enough to kill the parasites lodged there. If these tests are successful, it will still take another ten years of clinical trials before any drug is on sale.