20/12/22

Collaborative R&D vital to stem rare diseases in Africa

By: Jackie Opara

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

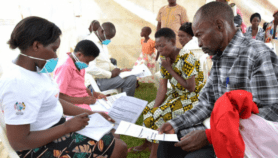

[LAGOS] At the Ipakodo Health Centre in the Nigerian city of Ikorodu, nurse Biola Daniels collects medical information on the antenatal ward from pregnant women with a history of anomalies.

“We have made it a point of duty to collect the history so we can pay more attention and refer them for testing or newborn screening for anomalies,” says Daniels, adding that such anomalies could help in diagnosing rare diseases.

The definition of a rare disease varies between countries and regions. The European Union defines a rare disease as one that affects one in 2,000 people, while the United States considers it a medical condition that impacts less than 200,000 people.

A study published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases in June says that almost six per cent of the world’s population could be affected by a rare disease.

According to the European Organisation for Rare Diseases, 72 per cent of rare diseases can be transferred genetically to children, with others resulting from infections, allergies and environmental factors.

Rare disease screening ‘out of reach’

While newborn screening can help identify rare diseases early, such services are often inaccessible, say health professionals.

“As much as we’re mobilising resources and working on the awareness, we can’t do it alone as a public health institution.”

Noella Bigirimana, Rwanda Biomedical Centre

“Newborn screening is not easily available in many government hospitals,” says Abiola Ejidokun, a gynaecologist at the General Hospital Ikorodu, in Nigeria’s Lagos state. “In the hospitals where they are available, they are expensive and many mothers who come here can barely afford it.”

Ejidokun tells SciDev.Net that even when newborn screening is available, healthcare workers tend to screen for one medical condition, usually sickle cell disease.

Faith Manuwa, the chief medical director of Malens Medcare Limited, a Nigerian medical diagnostics and biomedical services company, says the non-availability of diagnostics makes it difficult for the health sector in Africa to tackle rare diseases holistically.

“We see that some of the diseases that present more recently are inherited metabolic diseases, but then nothing happens beyond that,” she explains.

Inherited metabolic diseases

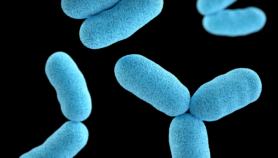

A study published in the European Journal of Human Genetics in May, explains that inherited metabolic disorders (IMD) are examples of rare diseases linked to genes.

“The disorders are individually rare. They represent a common group of diseases with a prevalence of 1 in 784–2,555,” the study says. “Currently, over 1,400 IMDs are recognised. Early disease recognition, accurate diagnosis, and treatment are lifesaving in many cases.”

Peter Bauer, chief medical and genomic officer at Centogene, a healthcare company focused on rare diseases tools, explains that an integrated diagnostic approach is needed for improving the diagnosis and early detection of IMDs.

“Some IMDs are treatable. Many are included in newborn screening programmes in various countries, but are very low in Africa,” says Bauer, a co-author of the study.

Bauer led a team of researchers to develop a new next-generation sequencing panel with more than 200 genes which integrate genetic and biochemical testing performed in the same laboratory to allow the efficient diagnosis of more than 180 metabolic diseases.

Diagnosing rare diseases in Africa

Barriers such as insufficient funding, lack of political support, and weak health systems make diagnosing rare diseases difficult in Africa, says an article published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases by the rare disease working group of the H3Africa Consortium.

The lack of diagnostic tools increases the chances of false positives and wrong classification of germs that cause rare diseases, the article adds.

Manuwa urges African governments to boost the infrastructural capacity at government hospitals and facilitate collaboration between government and private hospitals to increase diagnosis of rare diseases. She believes training of healthcare workers on rare diseases is also vital.

“Newborn screening is meant to be the norm but it is not available.”

Faith Manuwa, Malens Medcare Limited Nigeria

“We also need inter-regional research to find sustainable solutions and build a formidable genomic data hub,” says Manuwa.

Diseases that should be curbed at the newborn stage “linger on and cause the patient damage at adulthood”, she says, adding: “Newborn screening is meant to be the norm but it is not available.”

Endometriosis: ‘a silent rare disease’

One such disease is endometriosis, which occurs when tissue that usually lines the womb can be found on the ovaries, fallopian tubes or the intestines.

Abayomi Ajayi, a co-founder of African Endometriosis Awareness and Support Foundation and managing director of Nordica Fertility Centre in Nigeria, says that endometriosis is a silent rare disease often misdiagnosed and mismanaged in Africa.

“One in ten women, representing 200 million women and girls are living with endometriosis globally,” Ajayi adds. “The pain usually disturbs their normal chores. They also experience abnormal bleeding which can come from the navel and cough out blood.”

Ajayi tells SiDev.Net that about 40 to 50 per cent of women living with endometriosis could have fertility issues.

Kgomotso Mpho Gagosi, Botswana-based co-founder of African Endometriosis Awareness and Support Foundation, says that she was misdiagnosed several times when doctors did not understand while she was bleeding so much since she was 14 years old.

Kgomotso Mpho Gagosi, Botswana based co-founder of African Endometriosis Awareness Support Foundation and Endometriosis survivor

“I was told I have sexually transmitted disease when I have never had sex in my life. One doctor even told me I had undergone abortion because I was bleeding heavily,” Gagosi says.

She adds that she had several tests but nothing could point to what she was going through.

“Early diagnosis is important. Unfortunately, endometriosis has no cure,” says Ajayi. “This is a condition that they have to live with, till the stage of menopause.”

Collaboration ‘crucial’

Noella Bigirimana, a public health expert and deputy director-general of the Rwanda Biomedical Centre, says that regional collaboration and consolidation of efforts are key to controlling rare diseases in low-income countries.

“Rare diseases affect a lower proportion of people and may not receive attention,” she explains.

Bigirimana says that investment in primary healthcare has benefited both infectious and chronic diseases such as HIV, and hopes that rare diseases will also get the needed attention.

Bigirimana calls on public health workers to collaborate with organisations that focus on such diseases to increase their awareness in communities.

“As much as we’re mobilising resources and working on the awareness, we can’t do it alone as a public health institution,” she explains, adding that families and communities should also be actively engaged to help patients with rare diseases.

This story was produced under National Press Foundation Rare Disease Fellowship 2022.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.