Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

This article was supported by Lloyd’s Register Foundation

COVID-19 has underlined the urgent need for investment in accessible mental health services, say practitioners and patients.

[SÃO PAULO/KAMPALA] Luden Viana’s band had been gaining ground in the Brazilian alternative rock scene while he was working as a freelance film editor. But all this changed by March 2020 as COVID-19 took the country by storm.

In an attempt to stop the virus spreading, local authorities prohibited mass gatherings. “We could no longer perform,” Viana tells SciDev.Net from his home in Morro Grande, on the outskirts of São Paulo.

Jobs also became scarce. “Losing all my income sources triggered feelings of fear and anguish, which later evolved to anxiety and depression,” the 31-year-old says, adding that he eventually sought help and received medication for insomnia, depression and anxiety.

Like Viana, thousands of people worldwide developed some pandemic-related mental health problem. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25 per cent in 2020, the first year of the pandemic, adding to the nearly 1 billion people who were already living with a mental disorder globally.

![[Photo: Foto Pessoa no capuz cinza sentado na cama – Imagem de Cinza grátis no Unsplash]](https://www.scidev.net/global/wp-content/uploads/Mental_Health_sam-moghadam-khamseh-BODY.jpg)

A person pictured alone in a dark room in Tehran, in 2020. Anxiety and depression increased globally by 25 per cent in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, says the WHO. Photo by Sam Moghadam Khamseh on Unsplash

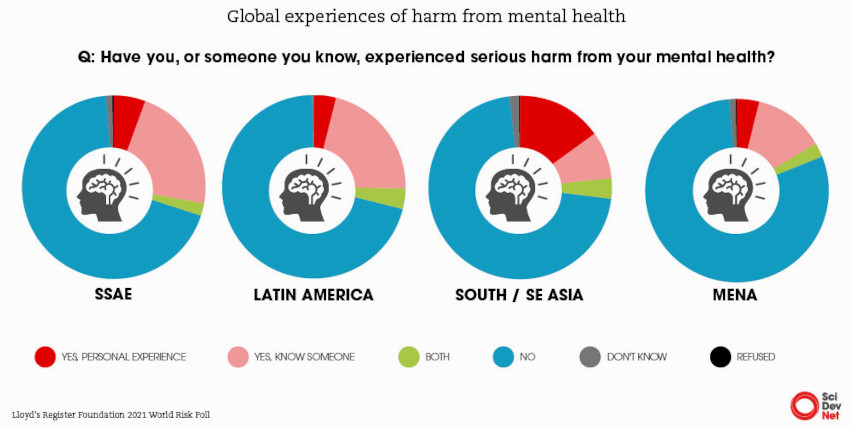

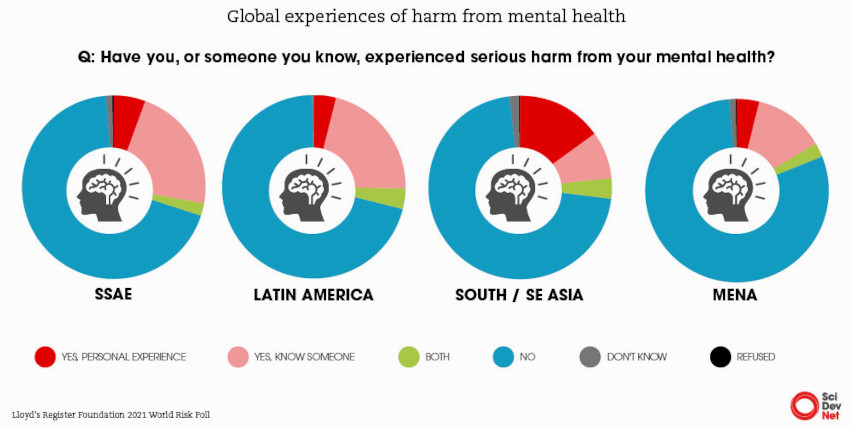

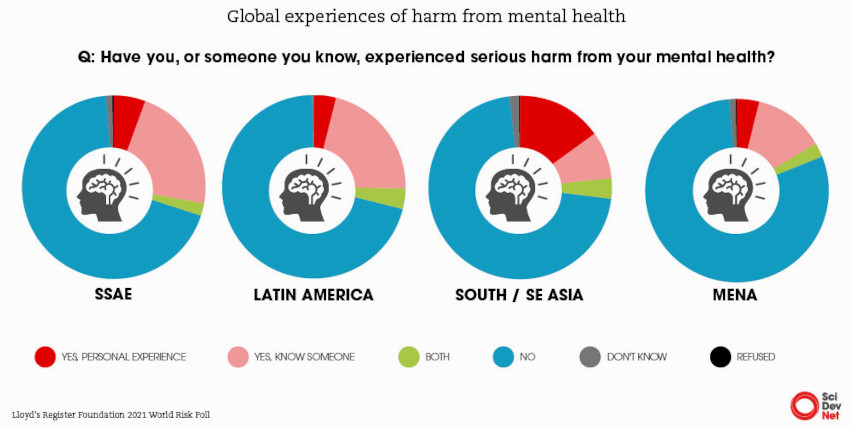

The 2021 edition of The Lloyd’s Register Foundation World Risk Poll shows a worldwide increase in experience of harm related to mental health issues of five percentage points, compared to the findings of the first edition in 2019, making it one of the most increased sources of harm highlighted by the study.

“When I fell ill with COVID-19 in 2021, I not only battled the virus but also faced stigma from my own community.”

Florence Awuma, COVID-19 survivor, Uganda

The findings are based on more than 125,000 interviews conducted by polling organisation Gallup in 121 countries, including places where there is little or no official data on such issues.

Increases were seen across all global regions and country incomes groups, including Sub-Saharan Africa, where about three in ten people said they had personally experienced, or knew someone who had experienced, serious mental health harm in the past two years.

Worries caused by the eminent risk of infection and dying from COVID-19 was one of the main stressors affecting people’s mental health, particularly those in high-risk groups or whose jobs involved physical interaction, such as health workers.

In constant contact with infected patients, physicians, nurses, first responders, and community health workers underwent intense stress during both the first and second peaks of COVID-19. Many of them developed symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as irritability and insomnia, linked to fears of infecting or losing family members.

For others it was the actual impact of contracting the disease that led to or exacerbated mental health problems.

‘Isolation and abandonment’

“When I fell ill with COVID-19 in 2021, I not only battled the virus but also faced stigma from my own community,” says Florence Awuma, a COVID-19 survivor from northern Uganda. She says even her own family shunned her during her time of need.

Suffering intense pain from coughing and breathing difficulties, the 51-year-old market vendor received treatment at the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of Lacor Hospital, in the city of Gulu, after contracting the virus.

“I am still on the path to recovery, and I continue to grapple with difficulties and persistent pain in my left side,” she says, explaining that long-term symptoms, such as a persistent cough accompanied by thick saliva, have fuelled the stigma.

“I also still have mental illness because of the isolation and abandonment,” she adds, keen to speak about her experience to raise awareness of the virus and preventative measures.

“I get very sad sometimes.”

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on mental health around the globe, leading to increased stress, anxiety, and sadness. Across Africa, many people are still struggling with heightened stress and anxiety, particularly in relation to financial stability and employment, experts tell SciDev.Net.

“COVID-19 has left a significant imprint on individuals and communities across Africa, particularly in the realm of mental health,” says Naeem Dalal, a psychiatrist and mental health consultant based at the Zambia National Public Health Institute.

A COVID-19 ward at Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala. Credit: John Musenze

“The fear of falling ill, and concerns about an uncertain future weighed heavily on individuals’ minds,” Dalal said.

“Measures such as lockdowns and social distancing fostered a sense of isolation, further amplifying feelings of loneliness and apprehension.”

All this has led to elevated rates of stress, anxiety and fear, says Dalal. But despite the widespread impact on mental health, some people remain hesitant to seek help due to fear of judgment or discrimination, he says.

Juliet Nakku, executive director of Butabika Hospital in Kampala, Uganda’s national referral hospital for mental health, says the pandemic exacerbated existing mental health challenges as uncertainty loomed large.

“There was a lot of sadness because many people were dying, many people were worried about whether they would live or die, or whether their significant others would live or die,” Nakku tells SciDev.Net in an interview at the hospital.

“Many people were worried about the economic situation that was going out of control during and after COVID.”

Lockdowns forced individuals to isolate, disrupting their social networks and affecting especially those who lived alone, she says.

“While [mental health] conditions existed before COVID […] during and after the pandemic, particularly, there was a spike in a number of these conditions,” adds Nakku, citing as examples conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders and the effects of alcohol and substance abuse.

Many people faced severe depression and anxiety following their COVID recovery, with insomnia becoming widespread, particularly for those who had experienced severe COVID symptoms and ICU stays, Nakku explains.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, where 40 per cent of the population were already living below the US$1.90-a-day poverty line according to the World Bank, the harsh economic consequences of the pandemic were acutely felt. Job losses and business closures were commonplace and the financial turmoil made it difficult for people to meet basic needs, such as food and housing, intensifying stress and anxiety.

Home working

The shift to home office work affected many people in countries such as Brazil, which has the highest level of reported serious mental health harm in the Latin America and Caribbean region, according to the World Risk Poll.

More than two in five people (44 per cent) in the country said they or someone they knew had experienced this in the last two years, compared with the regional average of about one in three (29 per cent).

“Telework during the pandemic has exacerbated social isolation and work-related stress, loneliness, family conflicts, and also food and alcohol consumption,” says psychologist Bruno Chapadeiro, a researcher at the Fluminense Federal University, in Rio de Janeiro.

Chapadeiro has been studying the impacts of COVID-19 on the mental health of Brazilian workers since the start of the pandemic. “We observed that many employees working from home felt like they needed to appear online and get in touch with their bosses more often to show they were still productive,” he explains.

He says the fear of losing their jobs has made many feel insecure and stressed, pushing people to work harder and eventually leading to burnout.

People wearing masks wait at a bus station in Curitiba, Brazil, in September 2022. Some people developed a fear of leaving home and mixing with others during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo by Mateus Ferreira on Unsplash

“When faced with going back to in-person work, many anticipated negative impacts due to concerns about COVID-19 safety,” Chapadeiro adds. “The isolation made them develop a sort of ‘social phobia’.”

Researchers at the Institute of Psychiatry of the Clinical Hospital of the University of São Paulo’s School of Medicine say this “specific phobia”, linked to the fear of catching COVID-19, was something people had not experienced before.

“Fear and anxiety are common and expected psychological responses in situations like this, but sometimes, under specific circumstances, some anxiety-related disorders can emerge,” says University of São Paulo psychiatrist Rodolfo Damiano.

In these cases, patients may avoid leaving home, touching objects, and talking with people, including their own family.

Journalist Ana Paula Freire, 53, used to experience panic attacks every time she went to the supermarket or the drugstore.

“I was scared to death of getting COVID-19,” she says. “I have chronic rhinitis and a compromised sense of smell, so I used to get up early in the morning to ‘eat’ my toothpaste and check if I still had taste, because I thought I had been infected all the time.”

‘Zoom dysmorphia’

For some, viewing themselves on camera for long periods has led to warped perceptions of self-image, triggering so-called “Zoom dysmorphia”.

“As video calls have become commonplace, some people felt that their facial flaws were magnified on camera or that their colleagues were constantly scrutinising their looks,” Chapadeiro explains.

“This not only caused anxiety but also led to feelings of needing to change or fix one’s appearance.”

Telework during the COVID-19 pandemic led to increased social isolation, stress, and loneliness, say psychologists. Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash

This was the case for Maria (name has been changed), who works in a Brazilian university. She shifted to homeworking during the pandemic, giving classes through Zoom.

“I used to spend long hours in front of the camera between classes and meetings, constantly looking to myself, to the point where I started feeling uncomfortable with my nose,” she says.

Maria had already been undergoing psychiatric treatment for anxiety and sleep problems. In 2021, she decided to undergo rhinoplasty, to alter the appearance of her nose. “Nobody in my family understood why I did this,” she tells SciDev.Net.

“Even I started to feel regret and fear that something might go wrong, requiring me to go to the hospital and potentially get infected with COVID-19.”

Services inaccessible

Accessing mental health support during the pandemic was a challenge due to healthcare systems being primarily focused on COVID-19 response efforts. This left some individuals without the necessary mental health assistance when they needed it most.

Jackie Nankya, a COVID-19 survivor living with a disability in Busabala village, in central Uganda, highlighted the particular challenges faced by people with disabilities during the pandemic and lockdowns. She says accessing essential services, including vaccinations, was difficult due to inaccessible vaccination centres crowded with long queues.

“It was difficult to access the vaccines,” says Nankya who walks with crutches following a motorcycle accident and said she started feeling anxious once she thought about access.

“We went to the health facility more than two times a day but the queues were too long,” she explains, stressing the need for health authorities to design inclusive programmes for future health emergencies.

The mother-of-two also shared her personal struggle with post-infection health issues, particularly related to breathing and depression, which have significantly impacted her daily life.

Accessing mental health public services was also difficult during this time, as many closed due to the risk of contagion. In countries like Brazil – an upper-middle-income country – those who had private health insurance were able to have online therapy and obtain digital prescriptions, widening inequalities.

‘Conflicting guidance’

The way in which the administration of Brazil’s then president Jair Bolsonaro handled the health emergency also contributed to worse mental health outcomes for people confined to their homes, say experts.

A deserted metro station in São Paulo, Brazil, in March 2021 after Brazil implemented lockdown measures to curb a rise in COVID-19 cases. Photo by Matheus Farias on Unsplash

The Brazilian population faced conflicting recommendations, says Lucas Arrais de Campos, a doctorate student at Tampere University, Finland, who has been studying the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil.

“The president’s call for the reopening of schools and businesses contradicted scientists’ recommendations for physical distancing,” he tells SciDev.Net in a conversation via Zoom.

“People became insecure and started anticipating concerns and uncertainty on how long the pandemic would last.”

The pandemic also made grieving more difficult than usual. At the height of the pandemic, hospitalised patients were prevented from receiving visitors and many families and friends couldn’t say goodbye to their loved ones. In many cities, wakes were banned or the number of people limited.

A mental health unit at Gulu Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda. Credit: Uganda Radio Network (URN)

Brazilian Viana’s uncle was one of the early victims of COVID-19. “He got infected in April 2020 and died a few weeks later,” Viana says. “It was a shock that, added to the other problems, forced me to search for professional help and take medication.”

Viana says he is better now, but also finding it hard to adapt to a “new normal”.

Need to invest

The question facing researchers and policymakers in Brazil is how to manage the unprecedented number of people who may need mental health assistance, in the wake of the pandemic.

“Brazil needs to invest more in mental health, especially in primary health care,” says physician Helian Nunes de Oliveira, from the Minas Gerais Federal University’s Medical School.

“It’s not just about training psychologists and psychiatrists, but all professionals who interact with people in distress or with mental disorders.”

In July 2023, Brazil’s Ministry of Health announced that it would release R$200 million (US$ 38.7 million) to finance psychosocial care centres and therapeutic residential services in order to clear the queue of demands from municipalities for mental health resources. There were around 200 requests related to mental health on hold by early June, according to the ministry.

The forecast is that by next year the ministry will release a total of R$ 414 million to strengthen mental health assistance policies, which will represent a 27 per cent increase in the budget. “To get closer to countries with higher income, however, we’d need to be able to invest ten times more,” Oliveira points out.

“There was a lot of sadness because many people were dying, many people were worried about whether they would live or die, or whether their significant others would live or die.”

Juliet Nakku, executive director, Butabika Hospital, Kampala

While people in low- and middle-income countries are more likely than those in higher-income countries and territories to say they experienced serious harm from mental health issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, these countries are the least likely to devote substantial resources to mental health services, according to the 2021 World Risk Poll.

Repercussions of the pandemic on mental health have been augmented by the dearth of social security benefits in many such countries, as well as limited access to healthcare and poor income prospects.

A survey cited in the WHO’s World Health Report 2022 on household costs associated with mental health conditions in six countries across Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia found that households where someone had a mental health condition were economically worse off than control households.

Crisis not over

While the pandemic is no longer a global health emergency, the effects on mental health are ongoing.

At Uganda’s Butabika hospital, with an official capacity of 550 beds, admissions began to hit 1,000 as COVID-19 took hold, says the hospital’s executive director Nakku.

“As we speak, we range in the 1,200 people in admission, so the effects [of COVID] are probably still going on,” she adds.

Admissions to Butabika Hospital in Kampala, Uganda’s national referral hospital for mental health, surged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Credit: Esther Nakkazi.

Nakku believes that COVID thrust mental health into the spotlight, shedding light on a longstanding issue that many preferred to ignore.

“We made a lot of noise about mental health,” she says.

“Part of the reason why we have these numbers going up could be that there is more out there in the community […] it could also be because more people know a bit more about mental health so they know to seek help.

“The pandemic underscored the critical importance of mental well-being throughout Africa, as evidenced by a multitude of activities spanning from grassroots community efforts to leadership initiatives,” adds psychiatrist Dalal.

“This crisis has thrust mental health into the spotlight, emphasising that taking care of our minds is just as crucial as tending to our physical health.”

He stresses the need for tailored interventions for vulnerable populations, as well as ongoing research and monitoring to address the evolving mental health challenges in post-pandemic Africa.

Uganda has a slightly higher rate of reported serious mental health harm than the Sub-Saharan average, with one in three people in the country (34 per cent) saying they or someone they know has experienced it in the past two years, according the World Risk Poll.

However, the highest rate in Sub-Saharan Africa is seen in Mali, at 53 per cent – the only country in the region to report serious mental health harm from more than half its population.

Ed Morrow, senior campaigns manager at the Lloyd’s Register Foundation, says the findings should be used by governments, regulators, businesses, NGOs and international bodies, working in partnership with local communities, to inform and target policies and interventions that make people safer.

“The first two editions of the World Risk Poll took place in 2019 and 2021, giving us an opportunity to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic had impacted on people’s perceptions of risk around the world,” he says.

“Data for the third edition of the poll is being collected in the field right now, and will allow us to see if changes identified in the previous wave were short-term phenomena related to the pandemic, or part of a longer-term trend.”

This article was produced by SciDev.Net’s Global desk.

Lloyd’s Register Foundation is an independent global safety charity that supports research, innovation, and education to make the world a safer place. Its mission is to use the best evidence and insight, such as the World Risk Poll, to help the global community focus on tackling the world’s most pressing safety and risk challenges.