29/09/25

Tanzania keeps rabies end goal in sight

By: Syriacus Buguzi

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

This article is supported by SIDA

[DAR ES SALAAM, SciDevNet] Salama Issa watched in helpless shock as her seven-year-old son was set upon by a stray dog in Mmongo village, in the Lindi region of Tanzania.

Recalling the horrifying moment six months ago, she told SciDev.Net: “I had sent him to get my phone charged at a neighbour’s place.

“I heard him scream, ‘Mamaaa! Mamaaa!’ By the time I ran to him, the dog had already sunk its teeth in his thigh. He was bleeding.”

“Thanks to bold action, smart science, and community power, we are supporting Tanzania to turn the tide.”

Kennedy Lushasi, senior research scientist, Ifakara Health Institute

Frantic, Issa rushed her son to the village chairman who advised her to go to Sokoine Hospital in Lindi town, where the boy received injections to provide immediate protection from rabies.

Salama Issa’s son points to the scars left by a stray dog bite at their home in Lindi region, Tanzania. Credit: Syriacus Buguzi / SciDev.Net

“I was scared. People in my community were saying my son would get ‘Kichaa cha mbwa’

[rabies] if he didn’t get treated early,” she says, her voice still laced with the panic of that moment.

1,500 deaths and rising

Salama’s story is not an isolated case. Although her son was fortunate to have survived the bite, many across Tanzania are not.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 1,500 people die each year from rabies infections caused by a rabid dog bite, with children in poor communities worst affected.

For those who can access the rabies vaccine, the full series of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) vaccines costs around US$100, an amount far beyond the reach of many people in Tanzania where more than 40 per cent of the population fall below the international poverty line, earning less than $US2.15 a day, according to the World Bank.

This economic barrier means that rabies costs and deaths continue to pose a public health threat despite interventions.

However, after decades of research and a coordinated national effort, scientists say the narrative is changing.

By 2030, Tanzania aims to halve deaths from rabies within three years and reduce the costs by US$10 million, under the Zero by 30 strategy, which aims to end human deaths from rabies by 2030.

The roadmap has been recognised globally, with Tanzania’s national rabies control strategy officially endorsed by the World Organisation for Animal Health in 2025.

‘One Health’ focus

Kennedy Lushasi, a senior research scientist at the Ifakara Health Institute (IHI) who has been researching rabies for decades, is confident the goal can be met. The key, he says, is a coordinated “One Health” approach that tackles the disease at its source.

“For years, we focused on treating human victims, which is both costly and often too late,” Lushasi tells SciDev.Net.

“But thanks to bold action, smart science, and community power, we are supporting Tanzania to turn the tide.”

He says he teamed up with institutions like the University of Glasgow to tackle the problem at its source — the dogs — with the goal of breaking the transmission chain entirely by vaccinating the animal population.

Lindi, the region where Salama’s son was bitten by a dog and survived, is one of several areas where Lushasi’s team has led large-scale dog vaccination campaigns in rabies hotspots. Others include Serengeti and Mtwara in Tanzania, and Pemba in Zanzibar.

The strategy, he says, is to vaccinate at least 70 per cent of the dogs to create herd immunity, meaning that enough animals in an area are immune to the virus to stop it spreading.

On the island of Pemba, off the coast of Tanzania, Lushasi tells SciDev.Net that mass vaccination resulted in the elimination of rabies, and the island has remained free of the disease for over seven years.

Overcoming obstacles

But there are barriers to reaching all those who could benefit from the vaccine.

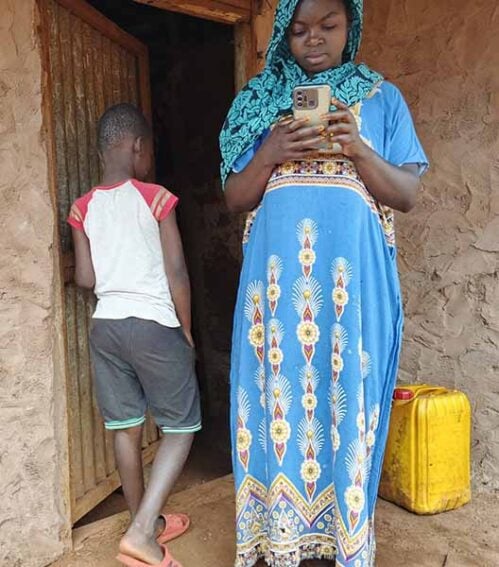

Salama Issa stands with her son at their home in the village of Mmongo, in Lindi region, Tanzania, where he is recovering from a dog bite. Copyright: Syriacus Buguzi / SciDev.Net

“Our villages are very distant, sometimes 50 to 80 kilometres from town,” says Naseeb Mokoa, a livestock officer for Lindi municipality.

A lack of electricity in many rural areas poses a significant challenge for preserving vaccines, which must be kept at a temperature of two to eight degrees Celsius.

Mokoa also laments the low public awareness around rabies.

“Many people don’t understand the dangers of rabies,” he says.

“When told they have to pay for the dog vaccination, most refuse. Community members are only motivated when they’ve witnessed a person or a dog in their area get rabies.”

To overcome these obstacles, the IHI team developed novel cooling containers to preserve vaccines and mobile apps for real-time tracking of vaccination coverage.

This data-driven approach has allowed researchers to identify areas with low coverage, where new outbreaks are most likely.

Researchers say this emphasis on evidence and data has been a key factor in Tanzania’s progress in tackling the disease.

‘Staggering losses’

The story of Salama’s son is one of human suffering, but the impact of rabies extends beyond public health, according to Ahmed Lugelo, a veterinary researcher with Global Animal Health Tanzania.

“The economic losses from this disease are staggering, especially for our pastoral and agro-pastoral communities,” says Lugelo.

“In Tanzania’s Mara region this year, we saw a single family lose eight cows, worth over 6.4 million shillings (US$ 1,800), to rabies after they were bitten by a rabid animal at night.

“These are not just statistics. These are families being pushed into poverty because a preventable disease wiped out their entire source of income.”

In communities without vaccination campaigns, people are stoning dogs to death due to fears of being bitten and catching rabies, according to Lugelo. But where vaccination is routine, dogs are accepted, cared for, and become part of the family, he says.

“Eliminating rabies isn’t just about saving human lives, it’s about protecting the right of dogs and other susceptible animals to live without fear of persecution,” he adds.

Harnessing innovation

While challenges remain, the approach used in Tanzania provides a roadmap for the rest of the continent, says Lugelo. He highlights the success of mass dog vaccination in Tanzania, Kenya, and other African settings, where at least 70 per cent coverage has halted transmission in parts of these countries.

“Scaling mass dog vaccination is logistically achievable if governments, research institutions, and communities work together,” he says.

“It requires strong political commitment, with national ownership, especially by the livestock and veterinary sectors — critical for securing budget allocations and vaccine procurement.”

A major obstacle is the lack of reliable cold-chain facilities below the district level. However, Tanzanian research and innovation is helping address this.

Thermotolerant rabies vaccines stored in Zeepot — a clay-based passive cooler that keeps them safe without electricity — allows vaccination campaigns to penetrate remote, off-grid areas, protecting more people and animals.

Human vaccination also still has a role to play. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance started supporting the role-out of rabies vaccines through routine immunisation programmes in 2024 in more than 50 countries.

Lugelo adds that a key part of rabies control is the system that connects veterinary and public health services, known as Integrated Bite Case Management.

“This dual system not only strengthens surveillance but also ensures that costly human vaccines are used efficiently and only when truly needed,” he explains, echoing Lushasi’s view that mass dog vaccination and integrated case management offer a robust, evidence-based framework for eliminating rabies across Africa.

Scaling these strategies continent-wide will require sustained investment, regional coordination, capacity building, and community engagement, scientists say.

Lugelo adds: “Tanzania’s experience shows that these strategies are not only effective but also feasible, making the goal of rabies elimination by 2030 an achievable reality”.

This article was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

The article is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), a Swedish government agency responsible for administering Sweden’s official development assistance.