26/01/26

How climate change is burning Kenya’s outdoor workers

By: Nelly Madegwa

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

For millions working outdoors in Kenya, climate change isn’t abstract, it is telling on their skin, writes Nelly Madegwa writes.

[NAIROBI, SciDev.Net] For eight years, Sylvia Muteshi has worked the tea plantations in Kakamega, western Kenya, starting at dawn and finishing near noon.

Working long hours under the sun without shade has taken a visible toll on her skin.

“At first, I did not think much about my skin, but over time I have noticed the changes,” she tells SciDev.Net.

“My skin is darker than it used to be and I have also noticed dark patches forming on my cheeks, marks that do not fade.”

Sylvia Muteshi, tea plantation worker, Kenya

“My skin is darker than it used to be and I have also noticed dark patches forming on my cheeks, marks that do not fade. Some of the other women say it’s from the sun—that the light stains our skin after so many years in the field.”

Across Kenya, millions of outdoor workers face this invisible threat.

Joseph Andove, a Nairobi boda boda (motorcycle taxi) rider, has an umbrella mounted on his vehicle. Originally for rain, now it protects him from the scorching sun.

“When it gets too hot, I use it so my skin doesn’t burn,” he says.

Farmers, construction workers, hawkers, and school children spend hours under what has become an increasingly dangerous sky. As climate change drives temperatures higher, our skin pays the price.

Research shows that while darker skin offers protection against sun-related skin cancer, Black Africans still face serious risks that many people don’t know about. When skin cancer does develop in Black people, it usually appears in unexpected places, under fingernails, on the palms of hands, or soles of feet, rather than sun-exposed areas.

Because patients and doctors often don’t expect skin cancer in these locations, it’s frequently caught too late.

Yet for many people with darker skin, the risks of prolonged sun exposure remain poorly understood, often dismissed under the assumption that melanin alone provides full protection.

A warming trend

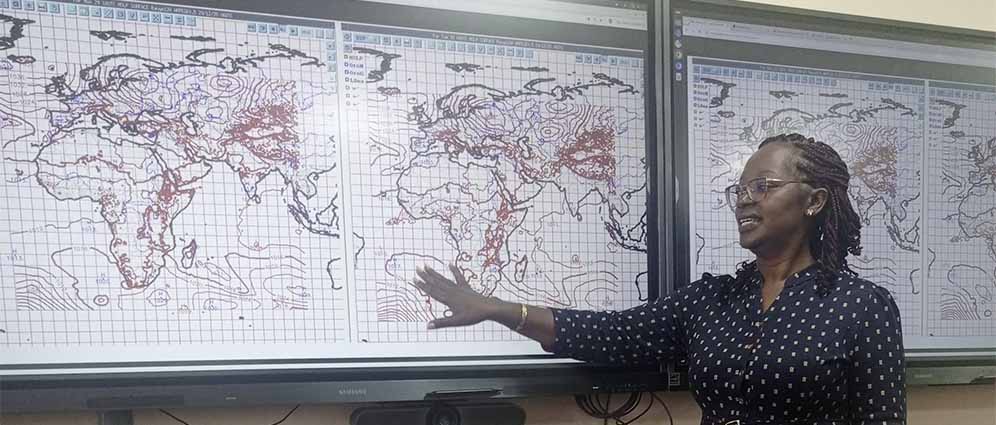

Patricia Nying’uro, a climate scientist at the Kenya Meteorological Department, says the country’s long-term climate data reveals an unmistakable warming trend.

“Our analysis shows that temperatures across Kenya have risen significantly,” she said. “Some regions, especially the coast and parts of western Kenya, have warmed by up to 2.1 degrees Celsius since record-keeping began.”

The central highlands, she adds, have also warmed, mirroring the global situation. Nying’uro’s team’s recent studies indicate that even though heatwaves have not been fully defined for tropical regions, Kenya is experiencing extended periods of extreme heat.

“One of the months that we found to have the most rise in temperature is the month of March, just before the rainy season,” she says.

“Because we have reduced cloud cover […] this means that more ultraviolet radiation reaches the surface.”

This pre-rainy season heat coincides with peak agricultural activity, when farmers spend the longest hours outdoors—a phenomenon many have come to expect, according to Nying’uro.

She adds: “A lot of the general public treat extreme heat as periodic. They think we can endure February and March because we know it’s going away.

“But this does not take into account that this is increasing yearly.”

Natural defences in question

This warming trend challenges a widespread belief across Kenya and much of Africa: that darker skin provides complete sun protection.

For generations, people across Africa have believed that darker skin offers complete protection from the sun’s harmful effects. “Our grandparents worked outdoors all day and they were fine,” is a familiar refrain.

But Wangai Mwatha, a dermatologist based in Nairobi, says that belief no longer holds true. “The sun today is not the same sun our grandparents experienced,” she explains.

Wangai Mwatha, dermatologist, has observed a steady rise in skin conditions linked to climate change and increased sun exposure.

“We have more heat, less cloud cover, and more reflective surfaces. The UV intensity is higher and that makes a big difference.”

Kenya’s position near the equator and its high altitude in many regions exposes people to some of the strongest ultraviolet radiation on earth. Deforestation, urbanisation, and reduced cloud cover have made things worse, leaving outdoor workers far more vulnerable to sun damage.

While darker skin does contain more melanin, which offers some natural UV protection, studies show it does not prevent sun-related problems such as pigmentation disorders, photoaging, non-melanoma skin cancers and sun allergies.

Skin problems on the rise

In her dermatology practice, Mwatha has observed a steady rise in skin conditions linked to climate change and increased sun exposure.

She says: “We’re seeing more cases of photocontact dermatitis, an inflammation of the skin caused by direct exposure to sunlight, and melasma, which leads to dark patches on the face influenced by environmental factors like intense heat and ultraviolet radiation.”

The changing climate, marked by hotter and dustier conditions, is taking a visible toll on people’s skin, according to Mwatha. “A hot, dusty environment leads to a lot of sweating,” she explains.

“Sweat in itself is not the problem, but when it stays on the skin for too long, it becomes a trigger for itching. That itching leads to scratching, and once you start scratching, you enter what we call the itch-scratch cycle.”

She says this cycle is especially problematic for people with sensitive skin or pre-existing conditions such as eczema or atopic dermatitis.

“If a child with eczema or even an adult keeps scratching their skin, it breaks the barrier and worsens the condition,” she explains.

Melanin protection

Dark skin contains more melanin, which does provide some protection, but it’s not foolproof.

Bianca Tod, a dermatologist and clinical trainer at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, explains that melanin provides sun protection, up to an SPF of 13, but says it is important to note that SPF only refers to UVB protection, not UVA.

This means people with darker skin can still suffer from sunburn, premature aging, and pigmentation disorders.

“Skin cancer among people with dark skin is less common, but when it occurs, it’s often diagnosed late and has worse outcomes,” Tod adds.

“That’s not about biology, it’s about awareness, access, and sometimes even stigma.”

Affordable habits

Joseph Andove; boda boda rider with an umbrella for protection from hot sunshine.

Tod says that sun protection should be seen as a set of everyday habits, not just a cosmetic choice. “Sun safety means layering your defences: hats, sunglasses, protective clothing, avoiding the midday sun, and using sunscreen when possible. Each measure adds protection.”

For millions like Sylvia, however, that protection is a luxury. A small tube of sunscreen in Kenya costs more than a day’s wages for a casual worker. “Sunscreen is out of reach for most people,” Mwatha admits.

“It’s often reserved for people with specific conditions such as albinism or genetic disorders like xeroderma pigmentosum.” Both these conditions increase the skin’s sensitivity to UV light.

Yet there are affordable alternatives. “If sunscreen is not accessible, wide-brimmed hats, long sleeves, and working in the shade can make a big difference,” says Tod. “Even applying sunscreen just on the face and hands helps.”

Mwatha adds that simple oils like petroleum jelly, shea butter, or coconut oil can form a basic barrier and keep skin hydrated.

“They will not block UV rays like sunscreen, but they help maintain the skin’s integrity,” she says. “And tree planting in farms, markets, and schools can restore natural shade—a long-term form of protection that benefits everyone.”

Climate extremes and skin disease

The impacts of climate change on skin go beyond sunlight. Rising heat and humidity are also changing the conditions under which bacterial and fungal diseases thrive.

Pamela Mwange, assistant director of biometeorology at the Kenya Meteorological Department, tells SciDev.Net that temperature and humidity patterns play a key role in skin disease trends. The biological mechanisms linking climate change and skin health are becoming increasingly apparent.

She says: “High temperatures and humidity increase sweating and moisture on the skin, making it very easy for fungi and bacteria to grow. We see more cases of fungal skin infections during hot and humid months.”

Strong UV radiation, she adds, damages skin cells and accelerates aging, while long-term exposure increases the risk of cancers.

Climate change has also led to shifts in rainfall, with some areas becoming more flood-prone and others experiencing prolonged droughts.

“Flooding exposes people to contaminated water, carrying bacteria and parasites that can cause skin infections,” Mwange says.

Pamela Mwange, assistant director of biometeorology at the Kenya Meteorological Department explains a phenomenon.

Meanwhile, droughts not only increase sun duration and consequently sun exposure but also lead to hygiene problems by limiting access to clean water.

“If water is not available for bathing and hygiene, this leads to more skin irritation and infections,” Mwange adds.

“Climate extremes—whether heat, drought, or flooding—all end up affecting the skin.”

Data and research gaps

The meteorologist also points out that Kenya’s monitoring systems still lack crucial data.

She says: “There is very little data on UV radiation levels, which are important for studying sun-related skin damage. We measure temperature, rainfall, humidity, and sunshine duration, but UV data is limited.”

Health records are also incomplete. “Many cases are just recorded as ‘skin infection’ without much detail. Are they related to weather? Are they related to pollution? There’s no classification,” Mwange explains.

“Without comprehensive records, it is difficult to track or predict trends. If we could integrate hospital data with weather trends, we could understand and predict outbreaks more effectively.”

Recognising the health risks accompanying rising temperatures, the Ministry of Health developed the Kenya Climate Change and Health Strategy (2023-2027). The plan aims to build a climate-resilient health system that can adapt to new environmental realities.

“The strategy is designed to guide Kenya in building resilience,” says Mwange. “It focuses on better data collection, improved disease classification, and setting up UV monitoring stations.

“Right now, different sectors are working in isolation. Meteorologists collect weather data, health workers see patients, but the information is not connected. If we can integrate climate and health data, we can protect people more effectively.”

Even as the effects of climate change are written on people’s skin, African populations remain underrepresented in global dermatological research.

“We still have major research gaps,” says Tod. “We know darker skin tones have lower rates of sun-related skin cancers, but we don’t fully understand other impacts like photoaging, eye damage, or pigmentation disorders in tropical climates.”

Late diagnosis, she adds, is shaped less by biology than by structural factors.

“That’s not about biology. It’s about awareness, access, and sometimes even stigma.”

Damage mitigation

Across Kenya, small but impactful initiatives are beginning to take root, which could help mitigate these health risks.

Schools and local authorities are planting trees and building shaded assembly areas to protect pupils from peak-hour sun. In Nairobi, a few county health offices have begun public awareness campaigns reminding residents to avoid direct sunlight between noon and 3 pm, wear hats, and keep skin moisturised.

There are signs of innovation too. A handful of Kenyan skincare startups are experimenting with locally made, mineral-based sunscreens using shea and coconut oils—products that could lower costs and make protection more accessible.

In the tea fields, Sylvia has stopped expecting her old complexion to return. “It’s like the sun has left fingerprints on my skin.” For her and many other outdoor workers like her, adopting habits to mitigate further sun damage is the only option in an ever-warming climate.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.