By: Malaka Rodrigo

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[COLOMBO, SciDev.Net] The devastation wrought on Sri Lanka by a cyclone that left hundreds of people dead was magnified by a failure to heed scientific warnings, say climate experts, who are calling for science-led rebuilding following the disaster.

The Indian Ocean island nation was battered by Cyclone Ditwah last month, leaving 643 people dead and more than 180 still missing, buried under mud or swept away, according to the country’s Disaster Management Center.

The cyclone bore down on Sri Lanka for several days, bringing heavy rainfall, triggering nearly 2,000 landslides, cutting off dozens of towns, and damaging major transport routes.

“This is an opportunity to rebuild the nation smarter and stronger—and based on science.”

Ananda Mallawatantr, technical advisor, UNOPS

As reservoir spill gates released surging water with little warning, downstream flooding became unstoppable, submerging even two-storey buildings in some areas.

Floodwaters inundated more than 1.1 million hectares, nearly one-fifth of the country’s land area, while landslides caused widespread destruction to homes, infrastructure and essential services.

A satellite image showing flooded areas in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s commercial capital. Copyright: UNDP Sri Lanka.

The full economic toll is still being calculated, but early estimates place the damage at US$6–7 billion, according to Commissioner General of Essential Services Prabath Chandrakeerthi. This represents three to five per cent of Sri Lanka’s gross domestic product (GDP).

A rapid assessment by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) found that more than half of those affected were already facing multiple vulnerabilities—unstable incomes, high debt and limited capacity to cope with shocks. Under such conditions, even moderate disasters can cause long-lasting setbacks.

Science ‘ignored’

Rohan Cooray, an independent climate change and disaster risk management specialist who assisted the disaster response operation, says the magnitude of the disaster reflects long-standing failures in planning, land governance and climate preparedness.

Sri Lanka has experienced extreme weather before, but Cyclone Ditwah’s impact was magnified by decades of ignoring scientific warnings, Cooray tells SciDev.Net.

For example, the National Building Research Organisation has, for years, produced detailed landslide-hazard maps identifying unstable terrain. Yet many of the landslides triggered by the cyclone occurred squarely within long-designated high-risk zones.

A family surveys their home destroyed by a landslide, searching for anything salvageable. Copyright: Aerial Vids SL Drona

“When a mapped hazard zone collapses, it is not just a natural disaster—it is also a governance failure,” Cooray says.

“The maps are clear. But land approvals and construction often proceed as though these risks do not exist.”

Slopes in Nuwara Eliya, Badulla, Kegalle and Matale—the worst-affected districts—have been destabilised over decades by unregulated construction, informal settlements, vegetable cultivation on steep slopes, and new roads but into hillsides that violated stability guidelines.

During Ditwah’s extreme rainfall, these weakened slopes had almost no capacity to absorb water or drain safely says Lalith Rajapakse, a professor of hydraulic and water resources engineering at Sri Lanka’s University of Moratuwa.

Early warning gaps

Ditwah’s explosive intensity is not a surprise as the Indian Ocean is warming faster than other tropical oceans, says Roxy Mathew Koll, climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology.

Between 1950 and 2020, the Indian Ocean warmed at 1.2 degrees Celsius per century, compared with about 0.9 degrees for global oceans, Koll tells SciDev.Net.

A warmer ocean fuels stronger, faster-forming cyclones—a trend Koll and others have warned about for years.

Climate change is also driving more extreme rainfall and several hill-country stations recorded over 300 mm within 24 hours during Cyclone Ditwah, according to the Department of Meteorology. Such rainfall intensity is enough to trigger landslides even on mildly unstable ground slopes, says Rajapakse.

The cyclone is Sri Lanka’s worst disaster since the 2004 Asian tsunami, which killed more than 35,000 people in the country.

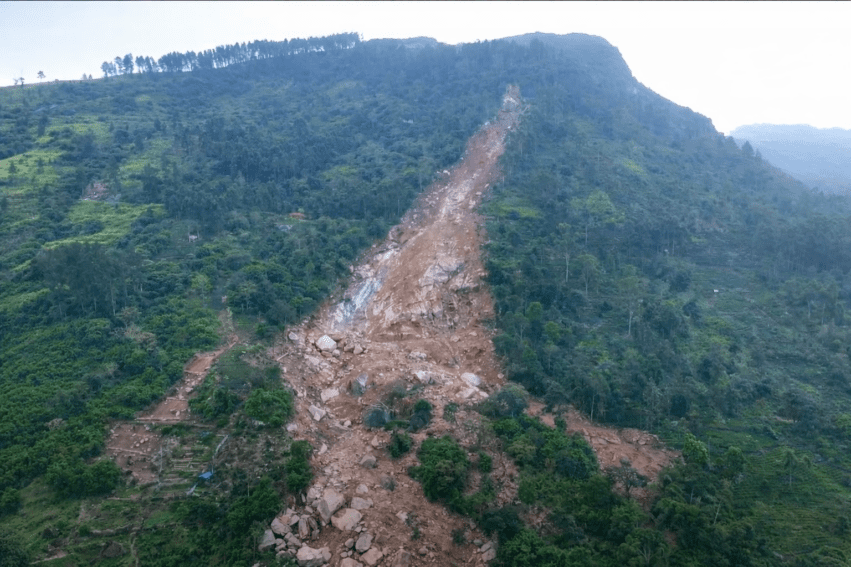

Landslides triggered by Cyclone Ditwah brought down soil and boulders, burying several villages in Sri Lanka. Copyright: Aerial Vids SL Drona

Despite improvements in Sri Lanka’s early-warning systems in the wake of that tragedy, Ditwah has revealed critical gaps. Some communities received warnings too late, while others received overly technical messages or unclear instructions, which were also not treated with the necessary urgency by affected communities, says Cooray. Widespread power failures further disrupted communication.

“Warnings must be actionable and consistent as communities need clarity, not fragmented messaging,” Cooray says. He stresses the need for clear, location-specific alerts, noting that technologies such as cell broadcasting, which can instantly deliver emergency messages to all mobile phones in a defined area, were available but not properly utilised.

Cooray, who has worked with numerous government and multilateral organisations on disaster response and urban planning, recalls helping set up such a system with a mobile operator, yet during Ditwah it appears these tools were not fully deployed.

In Sri Lanka, three agencies play central roles in extreme rainfall scenarios, namely the Department of Meteorology, the Irrigation Department, and NBRO. But they largely issue hazard forecasts which describe the weather itself—rainfall, wind, river levels—rather than what those hazards will do, according to Cooray.

The floodwaters reached nearly 720,000 buildings, about one in every twelve buildings in the country, according to the UNDP. Copyright Aerial Vids SL Drona

SciDev.Net reached out to these agencies but did not receive a response ahead of publication.

Cooray argues that Sri Lanka must shift to so-called “impact forecasting”. This means anticipating which areas will flood, where landslides are likely, and how many households could be cut off.

“Impact forecasts give decision-makers the information they truly need,” he says.

Science-driven rebuilding

Still recovering from its 2022 economic collapse, Sri Lanka now faces the enormous task of rebuilding damaged infrastructure and supporting affected communities.

Experts caution that reconstructing the way it always has will only set the stage for future disasters as climate extremes intensify.

“We cannot keep treating each disaster as a surprise,” says Ananda Mallawatantri, technical advisor on energy and climate change for the UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS).

“Climate change will make events like Ditwah more common, and the only defence is disciplined, science-led rebuilding aligned with climate adaptability,” he stresses.

Sri Lanka, he notes, has plenty of scientific expertise, but is missing the political will to consistently apply this knowledge in planning and regulation.

“This is an opportunity to rebuild the nation smarter and stronger—and based on science,” Mallawatantri says.

“It is an opportunity Sri Lanka cannot afford to waste.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia Pacific desk.