Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[GOIÂNIA, SciDev.Net] Known for the vibrant colour and sparkle that flood streets across the country each year, Brazil’s Carnival hides a serious threat to the environment.

A study conducted on a Rio de Janeiro beach during the world’s largest popular festival found a significant increase in microplastic concentrations in the sand.

Among the main culprits is glitter—an almost omnipresent feature of Carnival, used to brighten makeup, costumes and accessories at the annual five-day event in the capital and other coastal cities.

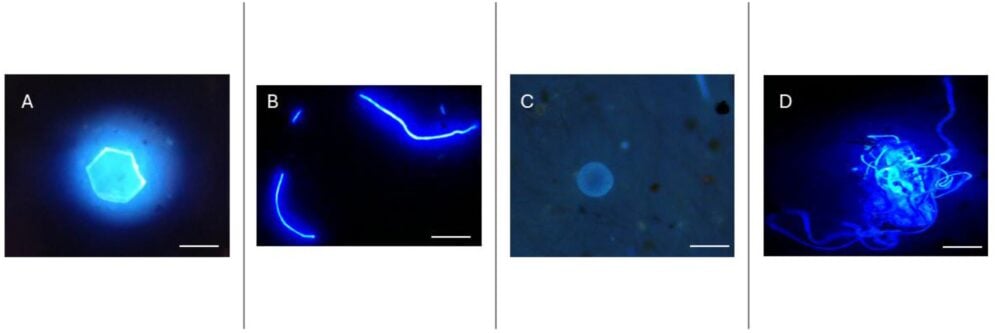

Glitter is classified as a primary microplastic, intentionally produced at a tiny scale of usually less than 5mm. Particles consist of a thin layer of plastic—typically Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET)—coated with a metallic film.

“The ideal would be to reduce the use of conventional glitter and promote environmental certification policies, marketing control and education for responsible consumption during Carnival.”

Tatiana Cabrini, ecology professor, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro

Its light weight means it disperses easily through air, water and physical contact.

Researchers collected samples along different stretches of sand along Rio’s 1.7 kilometre Flamengo Beach before, during and shortly after Carnival—which takes place each February or March. Eight months later, they conducted a fourth round of sampling.

Plastic fragments—including glitter—made up 66.3 per cent of all microplastics identified. Fibres accounted for 26.2 per cent, and granules 7.5 per cent.

Microscopic images of microplastics found on Flamengo Beach: a) glitter, b) fibres, c) granules, d) tangled fibres.

The study also showed that microplastic accumulation is not limited to the festival period. Even after Carnival ends, particle levels remain elevated for several days.

Dozens of street parades pass along the avenue bordering Flamengo Beach, with elaborate floats and people dressed in costumes, dancing to the sounds of Carnival music.

In 2024, when the study was carried out, Flamengo hosted 18 parades, including three that attracted more than 100,000 people.

That year, Rio de Janeiro’s government estimated the citywide festivities brought together around eight million people. More than 1,400 tonnes of solid waste were collected—over half generated by street parties alone.

Marine pollution

Even without directly analysing water samples, the researchers highlight Carnival’s potential impact on marine environments.

Tatiana Cabrini, an ecology professor at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro and one of the study’s authors, told SciDev.Net: “Microplastics deposited in the sand can be easily transported by the tides, wind and currents, and reach the infralittoral zone [submerged coastal area that is always covered by water] and then the adjacent ocean.”

Cabrini notes that Flamengo Beach sits within Guanabara Bay, an area already affected by domestic and industrial waste from 16 surrounding municipalities.

Microplastics can be ingested by animals that live on the seabed or by species that filter water to feed. These particles can retain toxic substances and heavy metals on their surface.

“These effects include obstruction of the digestive tract, reduced feeding capacity and physiological alterations,” Cabrini explains.

Biologist Luana Yoshida, who was not involved in the research, told SciDev.Net that the findings underscore the role of large events in dispersing particles such as glitter.

“Once improperly introduced into bodies of water—either due to lack of retention in the wastewater treatment system or directly as a result of festivities such as Carnival—and submerged, glitter reflects underwater light and reduces the radiation available to plants in that ecosystem,” Yoshida said.

Researchers have also observed that the metallic nature of glitter and its ability to reflect light can reduce water luminosity to levels that impair photosynthesis and the growth of aquatic plants.

In a study Yoshida participated in, glitter reduced photosynthesis rates by 30 per cent in elodea, or Brazilian waterweed—an aquatic plant that provides food and shelter for other species.

“These changes in primary production could generate other problems for the organisms in this ecosystem,” said Yoshida, a doctoral student in ecology and natural resources at the Federal University of São Carlos.

Alternatives

But how do you change a tradition so deeply rooted in Brazilian culture?

According to Cabrini, alternatives are emerging to reduce environmental impact. These include glitters made from regenerated cellulose, synthetic mica, seaweed, vegetable gelatin and natural dyes—materials that degrade more quickly.

“The ideal would be to reduce the use of conventional glitter and promote environmental certification policies, marketing control and education for responsible consumption during Carnival,” she said.

Yoshida agrees: “Although glitter is very attractive and has been part of our daily lives and festivities for a long time, it is not an essential item. So why not reduce its use or invest in less environmentally harmful alternatives?”

While research is still needed to assess the environmental risks of these substitutes, they are undoubtedly less harmful because they replace plastics that persist for years in ecosystems, she adds.

Regulation and bans

Glitter is already banned in some countries. The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) included it in regulations that prohibit microplastics intentionally added to products whose release into the environment cannot be controlled.

In California, USA, a proposed law would extend an existing ban on plastic microbeads to cosmetics containing glitter.

In Brazil, the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) issued a statement clarifying that no decorative powder—including glitter—containing micronized polypropylene can be used on food.

In addition, a bill has been put forward proposing to ban the manufacture, import, and sale of plastic and metal versions of the product.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Latin America and Caribbean desk.