By: Islay Mactaggart

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

When five time gold winning Paralympian Sophie Christiansen recently visited Rwanda, she was shocked by the stigma and lack of services for children with cerebral palsy.

Cerebral palsy (CP) covers a group of disorders caused by disturbances to the developing brain that can lead to seizures as well as problems with mobility, muscle stiffness, understanding and communication. [1]

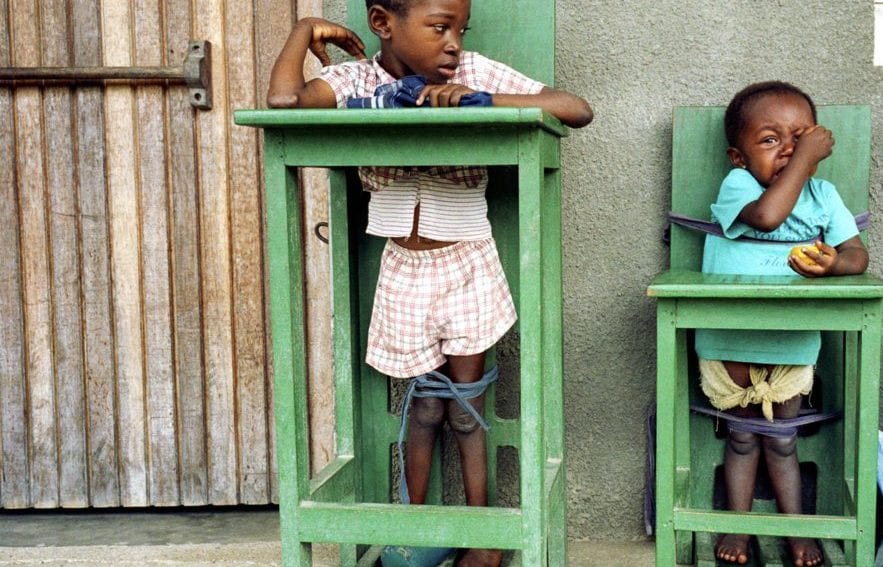

To improve their quality of life, children with CP need basic help such as physiotherapy to stretch their limbs. Simple, low-cost devices — such as therapy chairs made from layers of pasted paper and cardboard — can also improve independence and posture. One reason Christiansen didn’t see these in Rwanda is the limited knowledge about how many children with CP there are in the country, where they are and, consequently, what they need. Of course this is true of many poor nations.

Few epidemiological studies of cerebral palsy exist, but a recent study by the International Centre for Evidence in Disability (ICED) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom, showed the condition to be the largest single burden of disability among children in Bangladesh: 41 per cent of all children with disabilities in our study had CP. [2]

This study is one of only a handful of child disability studies globally. This is because child disability is relatively rare. To put it in perspective, in the Bangladesh study only about four children per 1,000 of the general population had CP, despite it being the most commonly observed disability.

This means large samples are needed to make meaningful conclusions — but gathering these requires time and money. As a result, there is limited data available both for development programmes and to generate evidence for service delivery and advocacy.

To try to change this, the ICED has just launched a guide to the Key Informant Method (KIM), a technique that allows children with disabilities to be identified ten times more cheaply — and therefore on a much bigger scale for the same money — than with door-to-door surveys. [3]

The idea is fairly simple. Researchers recruit and train volunteers called ‘key informants’ to identify children with disabilities in their communities. A ratio of one informant per 100 community members ensures the most accurate results. The volunteers, typically religious leaders or school teachers, are recruited based on their social standing and community knowledge.

Training involves learning to use a flip chart detailing specific identification criteria for each disability. In the case of CP, it includes guidance on identifying children who are late to stand or walk, or who have weak, stiff or floppy limbs. Key informants list all children who meet these criteria. A team of clinicians and social workers then assess the children and refer them to appropriate services.

Using the KIM in Bangladesh, my research team and I identified 953 children with cerebral palsy among a population of 258,000 children. In a neighbouring region of the country, we conducted a door-to-door survey of 8,120 children, identifying 21 with cerebral palsy. These proportions lead to a statistically similar prevalence estimate, but the KIM cost ten times less per child identified and therefore meant we could cover a far larger area (and far more kids) for the same cost. [4]

We discovered that the majority of these children had never previously received any rehabilitative support. Caregivers reported that lack of money and limited awareness of how services could help were the biggest barriers they faced. Following this finding, the ICED developed a parent-led training resource for the caregivers of children with CP. [5]

There is a huge, global appetite among people working with and advocating for children with disabilities such as CP for cheap and reliable ways to identify and support such children. Cutting the cost of identifying disabled kids would offer hope that more disabled children with will have their needs met and their opportunities for success maximised.

Islay Mactaggart is a research fellow in disability and global health at the International Centre for Evidence in Disability, part of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom. Before joining the centre in 2011 she worked for various disability and development organisations. Mactaggart focuses on disability measurement and has worked in countries including Bangladesh, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Haiti, India, Jordan, Myanmar, Pakistan and Thailand. She can be contacted on [email protected] and is on Twitter @IslayMactaggart

References

[1] M. Bax and others Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy (Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, April 2005)

[2] Gudlavalleti V. S. Murthy and others Assessing the prevalence of sensory and motor impairments in childhood in Bangladesh using key informants (Archives of Disease in Childhood, 2014)

[3] Islay Mactaggart Using the Key Informant Method to identify children with disabilities: A working guide (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2015)

[4] Islay Mactaggart and G. V. S. Murthy The Key Informant child disability project in Bangladesh and Pakistan (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2013)

[5] Getting to know cerebral palsy (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2013)