By: Baraka Rateng’

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NAIROBI] Africa needs to act fast to diagnose and treat hepatitis C if the continent hopes to achieve eradication of the disease by 2030 with the rest of the world, scientists say.

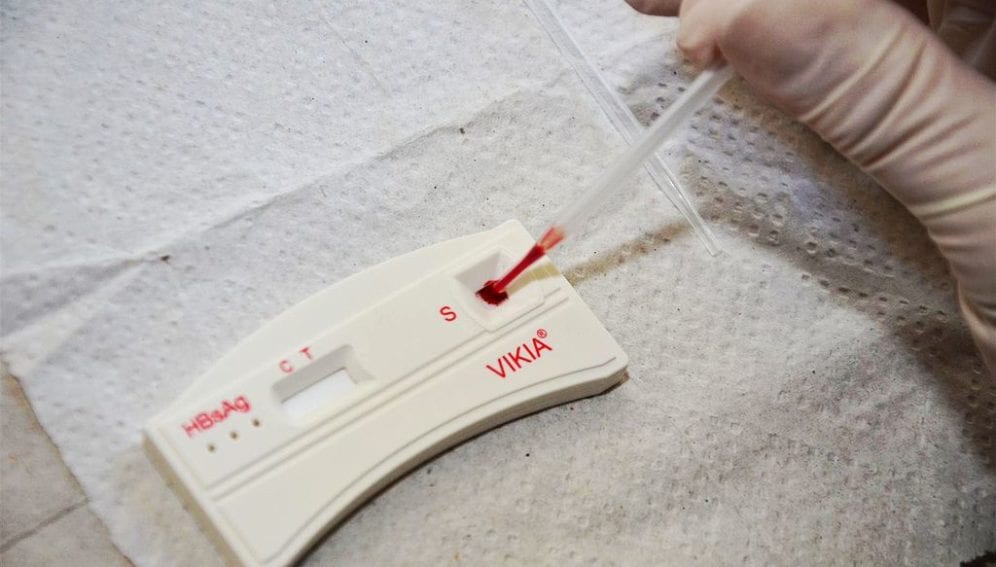

Hepatitis C, a liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus, can lead to a serious, lifelong illness. According to the WHO, about 71 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis C infection but there is currently no vaccine for preventing the disease, which can lead to liver cancer. Thus, screening for people at risk such as those with HIV infection is a key control strategy.

“We need to push governments to formulate national plans [to control hepatitis C],” said Emma Thomson, a clinical senior lecturer at the UK-based Glasgow University Centre for Virus Research, in an interview with SciDev.Net last week (15 January).

“We need to push governments to formulate national plans [to control hepatitis C”

Emma Thomson, Glasgow University Centre for Virus Research

Thomson adds that there are around ten million cases of active hepatitis C in Africa and countries with particularly high burdens include the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria. Globally there are about 400,000 deaths from hepatitis C annually.

Last year (2 November), Thomson and a team of researchers published a study in the Journal of Hepatology that showed that of 7,751 people in Uganda who were tested for hepatitis C, 266 (about 3.4 per cent) had the virus. Further tests identified two new strains of the virus in Uganda. The team also identified a new hepatitis C strain in two patients from the Democratic Republic of Congo who were tested.

The researchers say that the three new strains of the hepatitis C virus they identified in Sub-Saharan Africa may be difficult to treat. Research on the disease in Sub-Saharan Africa and other low-income regions has been limited mainly due to lack of funding.

According to the WHO, about 95 per cent of people with hepatitis C infection can be cured with antiviral medicines but access to diagnosis and treatment is low particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2016, the WHO announced its aim to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health problem by 2030 globally.

“Antiviral drugs not being as effective on the new strains should be alarming,” says Marianne Mureithi, a lecturer at the Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Nairobi, Kenya. “It means that the fight against hepatitis C in Africa has become more complicated than previously thought and a clear strategic plan has to be developed if the WHO is to achieve its target of ridding the world of the virus by 2030.”

She tells SciDev.Net, “While many countries within the region would struggle to fund research programmes on their own, a regional collaborative project involving several countries with the same identified strains could be the solution.

“If several countries share the financial burden and collaborate with the WHO, antiviral drugs for the newly discovered strains could be developed faster than waiting for Western drug companies to pour research and development into developing them.”

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

Chris Davis and others New highly diverse hepatitis C strains detected in sub-Saharan Africa have unknown susceptibility to direct-acting antiviral treatments (Journal of Hepatology, 2 November 2018)