Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

South Asian governments must recognise ‘hidden urbanisation’ and ‘urban divides’ in their countries, says Nalaka Gunawardene.

This is the only way they can cope with the formidable problems that threaten to overwhelm the region’s capitals as well as other cities and towns. These include some of the largest and fastest-growing urban agglomerations — extended city or town area with a continuous built-up area — in the world.

Making cities “inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by heads of state at the United Nations headquarters in September. [1] But that becomes a tough challenge for South Asian countries already struggling to manage their unplanned and chaotic cities.

The traditional approach to urban management — of expanding infrastructure — is proving woefully inadequate. Haphazard city development, even with huge investments, cannot accommodate the massive rise in both urban areas and city populations projected for the coming decades.

To face our decidedly urban future, we need a clearer understanding of the multiple factors involved. More rigorous survey methods, as well as new approaches like big data analyses, would provide valuable insights that can, in turn, lead to better policy responses. [2]

Messy, hidden urbanisation

Considering South Asia as a whole, 30 per cent of its 1.5 billion total population is currently categorised as living in urban areas. Since 2000, this urban share has grown only slowly, at around 1.1 per cent per year. But such official statistics miss out some ground realities.

A new study by the World Bank describes South Asia’s urbanisation as ‘messy and hidden’.

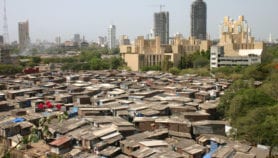

Messy, because cities have been growing outward, spilling over their administrative boundaries, rather than upward through the construction of taller buildings. And urbanisation is part hidden, because many places have acquired strong urban characteristics — but are not yet officially recognised as urban.

The most prominent sign of messy urbanisation is the estimated 130 million who live in informal urban settlements or slums. They inhabit poorly-built houses, have unclear land tenure, and lack access to basic services such as water, sanitation and schooling.

The Bank’s report, Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability, notes how these countries are not taking full advantage of urbanisation’s potential “to transform their economies to join the ranks of richer nations in both prosperity and livability”. [3]

To overcome the lack of updated urban data, the study’s authors have turned to an unconventional source: nightlights remotely sensed by satellites.

Nightlight maps of the world — using imaging by meteorological and earth observation satellites — have been compiled by the US space agency NASA since the turn of the century. [4] Analysing this data — freely available online — shows how South Asia’s urban areas have expanded at slightly more than five per cent a year between 1999 and 2010.

According to this analysis, our cities have grown about twice as fast in area as they grew in population. It suggests declining average city population densities and increasing sprawl.

The study says South Asia’s policymakers face a choice: continue on the same path, or undertake difficult and appropriate reforms to improve the region’s trajectory of development. It is not going to be easy, “but such actions are essential in making the region’s cities prosperous and livable”.

Urban divide

South Asia’s cities vary in size, diversity and complexity, but most have a large informal economy and a certain level of urban poverty. The two are interlinked as many services and trades rely on the poor who work on low wages and with little job security. In such settings, women are especially vulnerable.

Just as urban population figures are often off the mark, countries also lack reliable and current data on urban poverty and inequality. More importantly, poverty estimates based simply on income overlook other dimensions of deprivation such as poor health, lack of education, poor quality of work and threat from violence.

Infrastructural shortages and service delivery gaps are exacerbating a growing ‘urban divide’ in South Asia’s cities, warns the Mahbub ul Haq Human Development Centre (MHHDC) in Lahore, Pakistan.

In its Human Development in South Asia 2014 report, the independent think tank notes how most South Asian cities have bypassed proper planning during the initial stages of urban growth. This has led to congestion, inequalities, segregation, lack of public space and inadequate street patterns. [5]

Not just slums but other low-income suburbs with poor connections to the city can also be deprived of proper schooling and health facilities, the report says. This is the case with many sprawling new settlements on the outskirts of Lahore, Delhi and Dhaka. National- and local-level governance reform is crucial for redressing these imbalances.

One of the most striking facets of the urban divide is the rise of gated communities and other protected ‘enclaves of wealth.’

MHHDC says: “As more and more tracts of land and civic services are monopolised by those with the most resources, urban amenities are systematically denied to residents with lower incomes. On top of spatial segregation, gated communities and protected enclaves of wealth also result in social and economic segregation and even outright social exclusion.” [5]

Policy imperatives

To bridge the urban divide, MHHDC has identified four policy imperatives:

- Improve access to urban transport services;

- Increase affordable urban housing;

- Involve local communities, non-government organisations (NGOs) and private sector in water supply, sanitation and waste management; and

- Improve conditions of vulnerable youth, children and women to protect them from the ills of urban poverty.

But increasing the supply of infrastructure will not, by itself, bridge the urban divide. As MHHDC says, “It is not simply a question of building more roads to ease the traffic congestion, or installing more pumps to increase water supply.” [6]

Cities are as much social and cultural phenomena as they are physical structures and systems. A policy commitment to better urban governance and equality can slowly turn the urban divide into an urban dividend.

Nalaka Gunawardene is a Colombo-based science writer, blogger and development communication consultant. He tweets from @NalakaG

References

[1] SDG Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

[2] Big data can make South Asian cities smarter. By Nalaka Gunawardene. SciDev.Net. 31 March 2015.

[3] Leveraging urbanisation in South Asia. World Bank website. September 2015.

[4] NASA Earth Observatory: Night Lights analysis.

[5] Human Development in South Asia 2014 Report. Mahbub ul Haq Human Development Centre (MHHDC). September 2014.

[6] South Asia’s growing urban divide. Policy brief by Mahbub ul Haq Human Development Centre (MHHDC). September 2014.