27/04/21

Global definition ‘overestimates India’s child anaemia burden’

By: Neha Jain

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NEW DELHI] Anaemia rates among children and teenagers in India may be 20 per cent lower than currently reported as diagnosis is based on ethnically inappropriate blood count thresholds, a study argues.

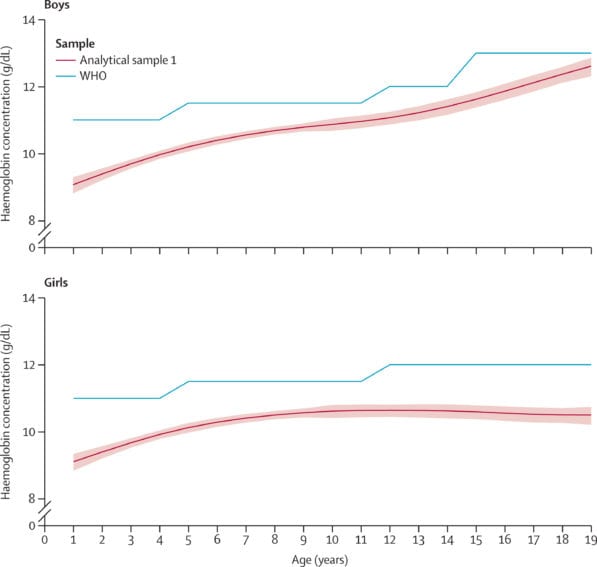

The study of haemoglobin concentrations in healthy Indian children aged zero to 19 found that the haemoglobin thresholds — or cut-offs — used to define anaemia were lower for both sexes and all ages than those recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Anaemia is a deficiency in the number of red blood cells or the haemoglobin concentration inside the cells, and is a serious global health problem. WHO estimated 42 per cent of children under five and 40 of pregnant women worldwide are anaemic. Common causes are nutritional deficiencies, genetic diseases of haemoglobin and infectious diseases.

For more than 15 years, experts have been calling for a re-evaluation of the WHO criteria for anaemia.

“WHO’s haemoglobin cut-offs to define anaemia were based on five studies of predominantly White adult populations, done over 50 years ago,” say the researchers.

The findings suggest that a single, global haemoglobin cut-off to define anaemia may not be appropriate for all regions and ethnic populations. The authors urge WHO to re-examine its cut-offs to define anaemia and issue updated guidelines based on recent evidence.

Published this month in The Lancet Global Health, the study assessed age-specific and sex-specific haemoglobin percentiles among healthy children and adolescents based on India’s first nationally representative nutrition survey conducted between 2016 and 2018.

Using the WHO cut-offs resulted in a prevalence of anaemia of 30 per cent compared with only 10.8 per cent using the study’s cut-offs. Differences in prevalence were higher among children aged 1 to 4 years and adolescents aged 15 to 19 years.

“The current use of WHO cut-offs which are Caucasian-based higher haemoglobin cut-offs to define anaemia substantially overestimates the burden in Indian children creating avoidable national stigma, lack of progress and emphasis on multiple routes to provide iron supplements and fortification apart from diet, and are unlikely to bridge the gap and have the potential to cause adverse effects,” says Harshpal Singh Sachdev, lead author of the study.

“The current use of WHO cut-offs which are Caucasian-based higher haemoglobin cut-offs to define anaemia substantially overestimates the burden in Indian children creating avoidable national stigma, lack of progress and emphasis on multiple routes to provide iron supplements and fortification apart from diet, and are unlikely to bridge the gap and have the potential to cause adverse effects”

Harshpal Singh Sachdev

The study’s cut-offs for haemoglobin were lower than the WHO cut-offs at all ages, with more pronounced differences in children aged between one and two, and in girls aged ten or above. Sachdev says that the onset of menstruation could be a contributing factor to the large difference in cut-offs for females above ten years.

Age-specific and sex-specific study cutoffs and WHO anaemia cutoffs in children and adolescents aged 1–19 years. Credit: Study authors/Lancet Global Health (CC BY 4.0).

“India should adopt these lower haemoglobin cut-offs instead of the present WHO cut-offs for diagnosing anaemia,” say the authors.

“These cut-offs might provide a closer estimate of the true burden of anaemia in the country than that calculated by using WHO cut-offs, its grading as a public health problem (mild instead of severe), and its responsiveness to appropriate public health interventions.”

Parminder S. Suchdev, associate director of the Emory Global Health Institute, who was not involved in the study, says that the authors used an approach that was similar to that of the WHO cut-offs, using the lowest five per cent of haemoglobin distribution in a healthy sub-population without known risk factors for anaemia.

“While these proposed thresholds may be more appropriate for the Indian population, it is difficult to assess the validity of lower thresholds that are based on statistical cut-offs not linked to specific physiologic or health outcomes,” Suchdev says.

He says the study had additional limitations, including not adjusting ferritin — the blood protein that carries iron — concentrations for inflammation, and not measuring an indicator of chronic inflammation known to affect haemoglobin concentrations.

“Despite these limitations, these findings address an important need to re-evaluate global thresholds to define anaemia using data from diverse populations and multiple geographic regions,” Suchdev says.

The WHO promised to review global guidelines on haemoglobin cut-offs to define anaemia. Experts are going to present and discuss evidence on haemoglobin concentrations to define anaemia especially among infants, children and adolescents this week at a virtual WHO meeting.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.