30/04/20

Uneven use of nuclear programmes across regions

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Five decades after signing the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, the broad development of this energy and other uses of its potential such as medical and research purposes are gaining momentum in the developing world.

Ildeu de Castro Moreira, president of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science, highlights three main important areas where research on nuclear field can contribute: “energy power as well as medicine for cancer diagnosis and treatments, and agriculture for food conservation”.

Moreira adds that all countries “have the right to do research in the nuclear field because it can contribute to everyday life and economics”.

“The treaty was fundamental to stimulate pacific uses, a key element for strengthening capacity building and development of the signing parties.”

Rafael Grossi, International Atomic Energy Agency

Nevertheless, the road to it is bumpy, it takes years of implementation and requires prepared human resources as well as investments in the order of billions of dollars.

In fact, many developing countries do not have the kind of skilled human resource or funding needed to properly start and operate a nuclear power plant. Furthermore, these countries are highly dependent on foreign experts, and for worst, a report released by the IAEA in 2004 points out to the fact that several nuclear experts were about to retire.

The IAEA is the United Nations’ centre for cooperation in the nuclear field and for promoting safe, secure and peaceful use of nuclear technologies.

Hossam El-Din Hassan, assistant professor of nuclear sciences at Sudan Atomic Energy Commission, explains to SciDev.Net that human resources difficulties can be addressed through training provided by international organisations such as the IAEA or countries advanced in the field including China and Russia.

“Perhaps the real crisis in terms of human resources is how to [retain] those talents after being trained,” he says.

He pointed out that Sudan has established a faculty for nuclear engineering to help the country with its peaceful nuclear programme. Unfortunately, inability to sustain those teams led to many of them migrating or shifting to other sectors.

Meanwhile, crossing the Atlantic Ocean, Latin American countries such as Argentina and Brazil despite joining other countries with nuclear capabilities since the1950s are suffering from inadequate investments for capacity building in nuclear development.

“The problem in Latin American countries is a financial issue because with every new administration, financial support for nuclear projects is interrupted,” says Norma Boero, former president of Argentinean National Commission of Atomic Energy.

“Three major projects in the nuclear energy sector are either interrupted or behind the schedule,” explains Aquilino Senra, a nuclear expert from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Argentina. “The Brazilian nuclear programme is not in a good moment due to budget limits.”

The three projects are a nuclear power plant for electricity generation, a nuclear reactor for research and production of radioisotopes, and a submarine with nuclear propulsion.

A need in Africa

Nuclear power should no longer be considered as a luxury but a need for African nations. However, the high cost of development, unavailability of skilled human resource and little understanding of nuclear technology are some of the main reasons Africa still lags behind in nuclear energy development.

In Africa, only South Africa currently stands as a country with nuclear power plants, which began operation in 1984 and have been producing about five per cent of the country’s electricity. In 2006, the South African government announced plans to build another plant to help meet the ever-growing demand for energy.

Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria and Zambia are some of the African countries already in talks with the IAEA to assess their ability to handle such a responsibility.

Countries such as Kenya, Sudan and Zambia mainly rely on hydroelectricity, and a 2.4-gigawatt nuclear power plant is capable of doubling their electricity supply.

Diego Hurtado, a researcher and former president of Argentina Nuclear Authority, agrees with Gatari that the land area for renewable energy including wind or solar is “far bigger than the one needed for nuclear energy”, with different studies indicating sizes from a dozen to hundred times more.

But Jaime Moragues, from Argentinean Association of Renewables Energy and Environment, disagrees for two main reasons: “You can use the land for agriculture in a wind power station, and it is also possible to install them in desert places,” he tells SciDev.Net. “So it is not good to compare required areas.”

In MENA, appetite for electricity

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), the picture is quite different. In the meeting round held in Khartoum, Sudan in 2006, the Arab League expressed its will to develop a nuclear programme for peaceful purposes to develop the region.

Although most of the designed programmes in the MENA region have not achieved tangible success throughout the years, the region’s need of electricity, securing exports of oil and endorsing economic growth have forced several countries to seek alternatives, one of which is launching or developing nuclear programmes.

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) figures, fossil fuels (oil and natural gas) constituted about 97 per cent of fuel necessities for electricity in the region in 2017. Meanwhile, electricity demands are expected to increase by 30 per cent in 2028, almost double the global rate, which is 18 per cent.

On the other hand, a report by the World Nuclear Association, released in January 2020, points out that the MENA region has one-third of the 30 countries in the world that have started planning or building their nuclear energy programmes.

Among the most prominent countries that work to advance nuclear capacities through this decade are Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. Together, these programmes could increase the nuclear capacity of the region to be more than 14 gigawatts by 2028, scientists say.

The United Arab Emirates has been leading other countries in the region after building the first unit of “Barraka” nuclear power plant, operating since February this year. It will be thus the second in the region that operates a nuclear reactor to generate energy after Iran, a country that has been operating its power plant “Bushehr 1” since 2011.

Ali Abdou, scientific advisor in the nuclear group Halliburton — a private enterprise — believes that nuclear energy has several advantages that makes it an excellent fit for the region.

“The energy produced per unit fuel is far more superior to any other form of energy; it is clean, efficient and reliable, which makes it suitable to substitute other forms that are not always available,” he explains to SciDev.Net.

According to the EIA, carbon emissions in the Middle East reached 2,000 million tonnes in 2017 as a result of burning oil and natural gas.

Abdou collaborated with other scientists to build and operate the Egyptian research reactor "EERR-2” in the mid-1990s in Inshas city, northeastern Cairo.

He underscores that the reactor has several uses in geological and medical research as well as nutritional and environmental sectors, among others.

Egypt signed an agreement with Russia in 2015 to build and operate four nuclear reactors with a total capacity of 4.8 gigawatts in Dabaa city in the country’s Northern West region. The first unit is expected to operate by 2026.

MENA: uses, hurdles and solutions

Ayman Abu-Ghazal, spokesperson of Jordan Atomic Energy Commission, says that “a peaceful Jordanian nuclear programme represents one of the significant exits for the country’s energy crisis”, adding that the country currently imports more than 90 per cent of its needs.

Jordan launched its research reactor in 2016 and plans to establish a nuclear plant for generating electricity and processing uranium, the main fuel for nuclear power plants.

In this regard, a joint report released by the country’s Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) and the IAEA in 2014, states that Jordan has good resources of uranium in comparison to other neighboring countries.

Khaled Debbabi, the president of the Tunisian Association of Nuclear Sciences and Techniques, says that “tensions in the geopolitical environment make the nuclear issue more controversial here than other regions”, adding that countries in the region are skeptical that their neighbours would not use their nuclear programmes for military purposes.

The Iranian nuclear programme had led the international community to impose economic penalties, under suspicion of using the energy for military purposes. This has been followed by years of negotiations until reaching a comprehensive agreement under the auspices of the IAEA in 2015.

Nevertheless, the United States abandoned the deal in 2018, resulting in increased tensions between the two countries. Iran started increasing its production of enriched uranium, according to IAEA reports, which has further raised some concerns in neighboring countries.

According to Hassan, military usage of nuclear energy would be an incalculable risk, and would lead to compromising potential developmental benefits of nuclear energy.

He cites South Korea as an example in the development of a peaceful nuclear programme, which has advanced its technologies and increasing its exports while North Korea has become isolated and suffering from development problems for choosing to use nuclear energy for military purposes.

Latin America’s ups and downs

Of the 450 nuclear reactors around the world, seven are in Latin America. The first in the region was installed in 1974 in Argentina, which today has three reactors (a fourth is being planned). It was followed by Brazil in 1985 (now with a second reactor in operation and a third in construction) and Mexico in 1990 (with a second plant in operation). In addition to electricity generation, other types of nuclear reactors are used in the region for research and applications in medicine and agriculture.

In Brazil and Mexico, nuclear plants generate about three per cent of the needs of each country’s energy. In Argentina the figure arises to up to ten per cent.

The Brazilian nuclear power plant for electricity generation — which is expected to produce 1,405 megawatts, a little more than one per cent of the country’s needs — was started in 1984. However, since then its construction has been interrupted several times, with only 60 per cent of the plant having been built.

Another project behind schedule in Brazil is the multi-purpose reactor for research and production of radioisotopes — active elements of radiopharmaceuticals, which are used as active agents in diagnosing and treating cancer and other diseases. The applications extend to agriculture, industry and the environment.

The submarine with nuclear propulsion —the third initiative in Brazil — faces troubles because of the complexity of the technology that is being developed.

“The first complexity is the compacting of equipment to fit in small spaces inside the submarine,” says Senra. “The second is the need to adapt the design to specific characteristics of the submarine according to sea conditions; and the last is the automation of the operation, because with the reduced space on the submarine only few operators can fit.”

Despite these challenges, Brazil has a national nuclear programme, including its use for uranium enrichment, and aiming to have autonomy by 2037. This is an important step because uranium found in nature does not generate energy.

Regarding Argentina, Boero highlights that the exports to Egypt, Algeria and India of molybdenum isotopes — good for diagnostic imaging — and “plates with low uranium enrichment, of only 20 per cent, a percentage that is good for peaceful use of nuclear energy,” could aid development.

Elena Maceiras, head of the Brazilian-Argentine Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials, adds that Peru bought from Argentina a reactor in 1988, which is currently fully operating for use in medicine and agriculture.

Chile, according to her, is evaluating building one for power supply. Currently, the country has two small research reactors. Colombia has had one since 1965 mostly for geological uses.

“Chile has all the credentials and possibilities to do it although now it is at a critical political moment because of months of disturbances and popular demonstrations,” she explains.

But some countries in the region planned to invest in nuclear projects with no success. For example, Venezuela signed in 2010 an agreement with Russia to build a nuclear plant but it was canceled after Fukushima disaster, as announced by the then president Hugo Chavez in March 2011. In Bolivia, under the Evo Morales government, similar plans were made but interrupted after he had to leave the country in 2019 to seek asylum in Mexico.

Different stages and concerns

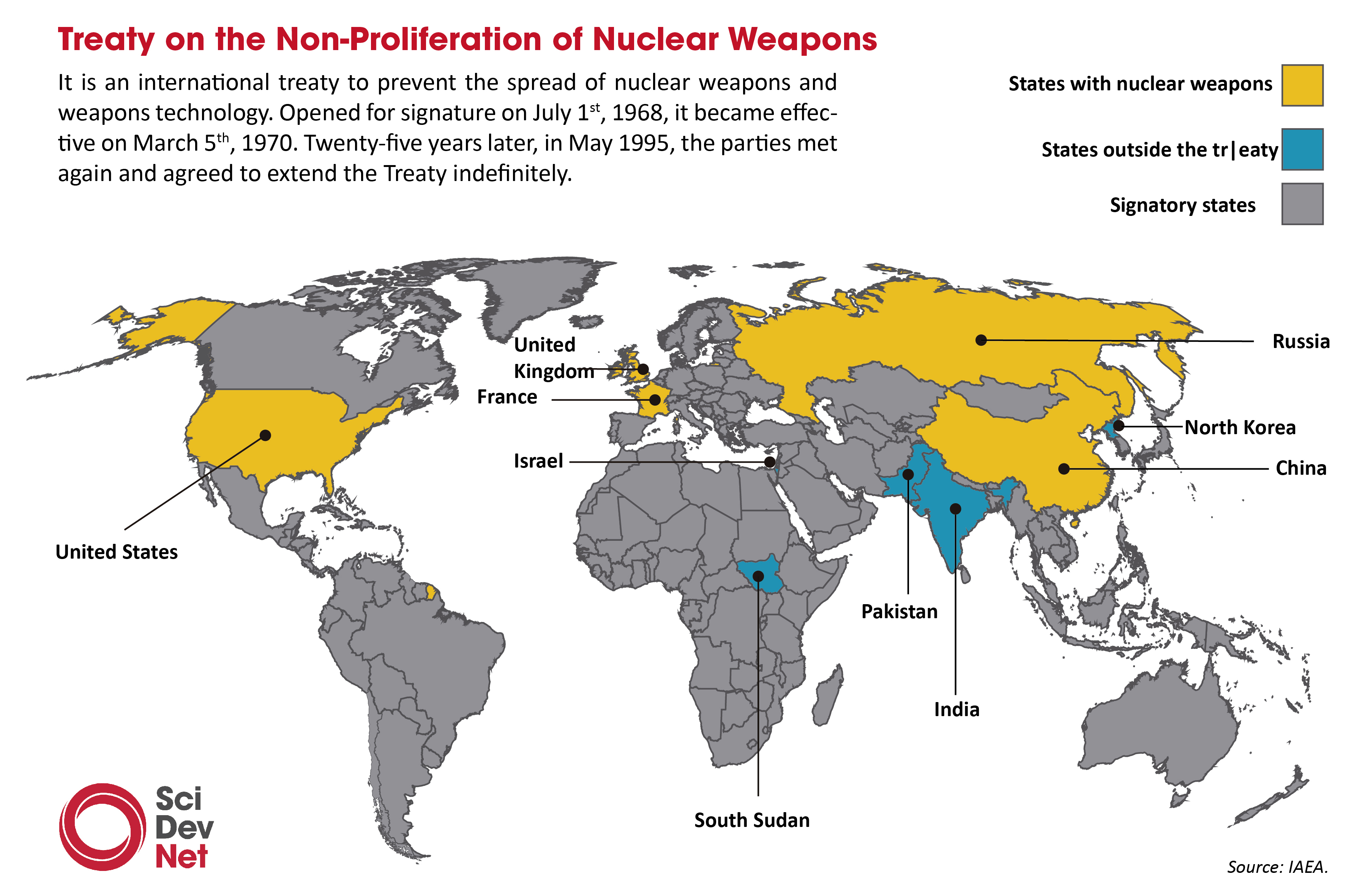

Currently, 171 nations have signed the treaty on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.

The treaty, which was first signed on 5 March 1970 by China, France, Great Britain, Russia [then called the Soviet Union) and the United States of America, aims to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, as well as to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses.

“The treaty was fundamental to stimulate pacific uses, a key element for strengthen capacity building and development of the signing parties,” says Rafael Grossi, director-general of the IAEA.

Nevertheless, catastrophes such as Chernobyl in Ukraine in 1986 and Fukushima in Japan in 2011, and other accidents including the reactor leak in Three Mile Island in the United States in 1979, have put spotlights on the risks that the development of nuclear energy can pose for society and the environment.

“Nuclear is not dangerous,” Boero tells SciDev.Net. “Saying that it is dangerous based on these two or three examples is similar to saying that boats are dangerous because the Titanic has sunk.” Still, the safety concerns have been highlighted in many countries in terms of what happens in case of nuclear accidents.

In Latin America, for example, two of the three Argentinean nuclear plants are less than 100 kilometers from Buenos Aires metropolis, which has about one-third of the population of the country.The three Brazilian nuclear plants are located about 160 kilometres from the second biggest city in the country — Rio de Janeiro — and in an area in which the roads are not highways and often face landslides.

Another controversial issue is nuclear waste. While some experts express environmental concerns regarding its disposal, nuclear energy defenders argue that this is key in times of climate change because it is an energy that does not release carbon dioxide.

For Maceiras, above nuclear there is always the shadow of policies on nuclear weapons. According to her, they are currently in a “delicate moment”, citing “the political situation in the Middle East, nuclear developments in Iran, for instance, and in North Korea, a country accused by the Western world of having nuclear weapons”. Every five years, experts meet to assess treaty. The next review conference was due this year in New York on 29 April-10 May but had to be postponed to latest April 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The debate about the nuclear developments in Iran and the proposal of United States to impose sanctions on that country because of its uranium enrichment programme were key points of the agenda.

In the last review meeting, five years ago also in New York, a final statement was not released because of the lack of consensus among parties.

According to Wilfred Wan, a researcher at the United Nations Instituted for Disarmament Research, the failure of the 2015 review conference to produce a consensus around the document “can be attributed to the discussions about the establishment of a nuclear weapon-free zone in the Middle East”.

“These are some of the reasons why the treaty needs a periodical review: to watch that every part is accomplishing their part," Maceiras explained.

*Disclaimer

*We have made corrections on the article to remove quotes erroneously attributed to Abulrazak Shaukat, director of the Division of Africa at the International Atomic Energy Agency. This correction was done on 13 May, 2020

More on Nuclear

News

Africa ‘entitled to reap the benefits of atomic energy’

There must be no restrictions on African use of peaceful nuclear technology, speakers said at the continent ...11/01/07

Opinion

The pros and cons of nuclear power in the South

Last month SciDev.Net published an editorial that examined whether developing countries should be moving to ...04/08/06

Opinion

The pros and cons of nuclear power in the South

Last month SciDev.Net published an editorial that examined whether developing countries should be moving to ...04/08/06

Editorials

Should developing nations embrace nuclear energy?

A combination of factors appears to be pushing the risk-benefit balance back into nuclear's fa ...21/07/06

Editorials

Should developing nations embrace nuclear energy?

A combination of factors appears to be pushing the risk-benefit balance back into nuclear's fa ...21/07/06

Feature

Not just weapons: nuclear science for development

Over the past decade, the UN's nuclear energy regulator has helped over 90 developing countries rea ...12/04/06

Feature

Not just weapons: nuclear science for development

Over the past decade, the UN's nuclear energy regulator has helped over 90 developing countries rea ...12/04/06

Editorials

Nuclear rights and responsibilities

The developed world has no right to dictate unilaterally to developing nations how they choose ...05/08/05

Editorials

Nuclear rights and responsibilities

The developed world has no right to dictate unilaterally to developing nations how they choose ...05/08/05