By: Baraka Rateng’

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NAIROBI] Elephantiasis linked to the exposure of bare feet to red clay soil from volcanic rocks is widespread in Cameroon and Ethiopia, two studies show.

In Cameroon, a study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Disease journal last month (11 January) shows low prevalence of the disease — also called mossy foot or podoconiosis because of its tendency to cause massive swelling of the feet and legs — but with widespread geographical distribution across the country.

The Ethiopian study published in the Wellcome Open Research on 15 December 2017 found that podoconiosis is endemic in 345 districts.

Kebede Deribe, a co-author of both studies and an honorary assistant professor at the Addis Ababa University, says the geographical distribution of the disease is poorly understood in countries historically reported to be endemic.

“Podoconiosis patients lose 45 per cent of their economically productive time because of morbidity associated with the disease.”

Kebede Deribe, Wellcome Trust Brighton and Sussex Centre for Global Health Research

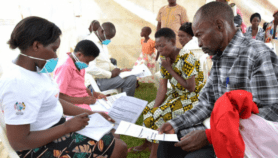

In Cameroon, researchers collected data from 10,178 individuals of at least 15 years old from 4,603 households, 76 villages and 40 health districts as part of nationwide survey in January 2017. In Ethiopia, data from 141,238 individuals from 1,442 communities and 775 districts were collected in June-October 2013.

The overall prevalence of podoconiosis in Cameroon was 0.5 per cent but was found in every region of Cameroon studied, says Deribe, who is also an epidemiologist at the UK-based Wellcome Trust Brighton and Sussex Center for Global Health Research, adding that in Ethiopia the prevalence was four per cent.

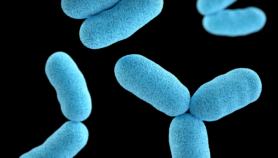

Podoconiosis, Deribe explains, occurs when minerals enter the lymphatic system through exposed feet and cause severe foot swelling. It occurs in highland red clay soil areas, mainly among poor, barefooted farming communities, who do not wear protective shoes or wash the dust off their feet using soap and water.

The disease also has severe social and economic consequences such as exclusion from school, churches and mosques, and from marriage with unaffected individuals.

“Podoconiosis patients lose 45 per cent of their economically productive time because of morbidity associated with the disease,” explains Deribe.

This disease is preventable if regular foot hygiene including wearing of socks and shoes is practised, according to Deribe.

“Measures to destigmatise [people with] the disease through public education about the prevention and treatment are critical,” says Deribe.

Results of the two studies, explains Deribe, will help decision makers at national, regional and district levels to “benchmark information for programme plans and policymakers for resources allocation and prioritise areas affected most”.

The disease, he says, is becoming a major health burden in Africa and has been reported in 18 countries: Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. In Ethiopia, he adds, over 1.5 million adults are estimated to be having the disease.

Christine Kihembo, a senior field epidemiologist with Uganda’s Ministry of Health, says the findings are largely consistent with previous studies.

A health system response to the burden of podoconiosis is important, through case surveillance and disease management, she says.

She notes that podoconiosis is a neglected tropical disease affecting about four million people, particularly in East and Central African countries, citing Central and South America and Southeast Asia as also the regions the disease is prevalent.

Among populations who work barefooted on irritant soils in endemic areas particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, as many as five to 10 per cent are living with the disease, she explains.

“We, therefore, must do more to improve podoconiosis control in high-risk countries by increasing coverage with proven interventions such as footwear and foot washing,” she says.Elimination of podoconiosis requires political will and commitment, policy formulation, and financial commitment by governments of endemic countries in addition to funding from donors, Kihembo adds.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

[1] Kebede Deribe and others: Mapping the geographical distribution of podoconiosis in Cameroon using parasitological, serological, and clinical evidence to exclude other causes of lymphedema (PLOS One, 11 January 2018)

[2] Kebede Deribe and others Estimating the number of cases of podoconiosis in Ethiopia using geostatistical methods (Wellcome Open Research, 15 December 2017)