By: Sophie Hebden

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

People’s risk of getting malaria is determined as much by their environment as by their genes, say researchers.

They say this means that increasing access to insecticide-treated bednets and healthcare is, in the short-term, an easier and more effective way of fighting the disease than trying to understand how people’s genes affect it.

Margaret Mackinnon of the University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, and colleagues spent five years recording new cases of malaria in more than 3,500 Kenyan children.

The team published their findings online yesterday (7 November) in PLoS Medicine.

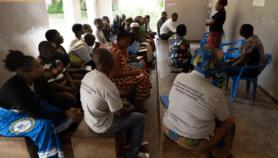

They found that genetic factors explained about a quarter of the variation in the risk of getting malaria. Meanwhile, 29 per cent of this variation was determined by which houses the children lived in.

Children in households with the most malaria cases got the disease twice as often as those living in houses with the fewest cases — even though the children played and ate together.

“It’s quite remarkable to see the variation in cases of malaria among children living almost side by side,” says Mackinnon.

Although the researchers have not yet identified what makes a household high risk, they say socio-economic factors could play an important part. For example, poor families often cannot afford housing materials and insecticide-treated bednets that would protect them from mosquitoes.

“Being able to clean up the backyard of mosquito breeding sites and to feed the children well will also affect their susceptibility to malaria — good general health will mean the children have stronger immune systems,” Mackinnon told SciDev.Net.

Although studying whether human genes protect against malaria could lead to improved prevention and treatment in the long-term, the researchers say it is important that people use existing low-tech measures to control the disease.

But other malaria experts believe this is easier said than done because although treated bednets are effective, their cost — even when heavily subsidised — is still too high for many of the world’s poorest people.

Indeed some — such as Jeffrey Sachs, director of the UN Millennium Project — say that providing bednets for free is the only way to tackle malaria (see The cost of making the poor pay).

Link to full paper in PLoS Medicine

Reference: PLoS Medicine 2, e340 (2005)