03/10/20

Boost training to stop rise in ‘devastating’ birth injury

By: Gilbert Nakweya

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

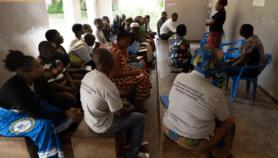

[NAIROBI] The number of women in Uganda suffering from obstetric fistula will continue to rise if they go to local traditional healers because healthcare facilities with trained staff are inaccessible, a study warns.

An obstetric fistula is a medical condition that is usually caused by prolonged, obstructed labour and results in a hole developing in the birth canal that can only be corrected through surgery. A vaginal fistula is similar but can have other causes, such as an injury or infection.

An obstetric fistula has devastating health and social consequences. Women can suffer infections, kidney disease and infertility and are often shunned by society due to incontinence.

“We need to determine why women do not reach healthcare facilities, and when they do, it is not as prompt as it is medically recommended.”

Betty Nannyonga, Makerere University

According to the study, published in PLOS One: “[S]ome of the women who reported having had vaginal fistula symptoms had sought some form of treatment. This proportion might however include women seeking care through traditional healers that could do little when modern interventions were needed.”

The researchers, affiliated with Sweden’s Linköping University, recommended that more funding be allocated to outreach health activities to support women who forced to seek out traditional healers when they are not able to get to health facilities.

Researchers compared rates of access to healthcare services by women of reproductive age before pregnancy, with access during and after childbirth to determine the potential for controlling obstetric fistula.

The study estimates that up to 22 in every 1000 women aged between 15 and 49 will experience obstetric fistula in Uganda. A Georgetown Law Journal study published in June says that 50,000 to 100,000 new cases of obstetric fistula occurred in low- and middle-income countries each year, but it was “eliminated” in high-income countries by “standardising health-provider training, increasing access to obstetric care, and improving surgical techniques”.

“We need to determine why women do not reach healthcare facilities, and when they do, it is not as prompt as it is medically recommended,” says Betty Nannyonga, lead author of the PLOS one study and a senior lecturer at the Department of Mathematics at Makerere University.

Nannyonga tells SciDev.Net that there must be a balance between outreach and service delivery if the country is to reduce the number of obstetric fistula cases.

“There cannot be service without women to treat, and you cannot invest to get them to the hospitals when [professional] healthcare is not available,” she explains. “There should be an optimal way of offering both outreach and healthcare at the shortest time possible with minimum investment.”

The study was conducted with data from the Uganda Demographic Health Survey of 2016 comprising 18,506 women aged between 15 and 49 in 15 regions of the country.

Researchers also analysed hospital records to estimate how many women were treated for fistula. Data obtained from Kitovu Hospital for 2009 to 2016 showed that 3,815 women did not receive treatment out of the 9,396 women scheduled to receive surgery.

Poorly trained birth attendants is also fuelling the rise in cases, says Peter Waiswa, associate professor of health policy, planning and management at Makerere University’s School of Public Health.

“The authors show that many women still do not get [professional] care at birth, and there are just too few fistula repairs that are ongoing to clear the backlog,” Waiswa, who was not involved in the study, tells SciDev.Net.

“This means that the cases are even going to increase more, which will make it very difficult to clear the backlog, yet the needed investment is so low. We must continue to invest to ensure that women currently come to facilities and get quality services.”

Waiswa reiterates that although facility-based care is increasing in Uganda and across Africa, "still too many women get fistula from hospitals" and other health facilities.

"Attendance of health facilities must be accompanied with quality provision of services. Unfortunately, this remains a huge — and perhaps the most important — gap," he explains.John Bosco Bomboka, public health researcher and senior consultant at Uganda-based Eastland Services says that outreach, such as health camps, can only be effective under the supervision of trained staff.

"Therefore, fruitful and effective fistula camps can be done without necessarily channelling funding away from health centres, but supporting health facilities to champion them since they require personnel like doctors and nurses, among others, to undertake surgeries," Bomboka adds.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.