By: Jackie Opara and Esther Nakkazi

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

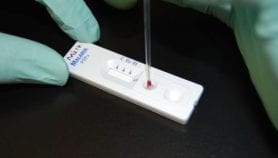

[KAMPALA] Fake and poor-quality antimalarials account for up to 43 per cent of annual economic cost of malaria in children under five years in Sub-Saharan Africa, two simulation studies suggest.

The WHO estimates that fake and poor-quality antimalarials contribute to 31,000–116,000 additional deaths annually in the region, with children under five years being the most affected. But researchers say that estimates of country-level health and economic impacts of fake and poor quality antimalarials are scarce in the region.

“When we looked at how prevalent poor-quality medicines are, and the negative health effects they can cause, we wanted to provide data and estimates that policymakers could use to understand the scale of the issue and act upon it,” says Sachiko Ozawa, lead author of the two studies.

Ozawa, an associate professor at the US-based University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy, and collaborators developed a model, and applied it to patient care-seeking behaviour and supply chain processes of antimalarials in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Kinshasa Province and Katanga region.

“The public can hold the health system accountable to deliver good quality medicines.”

Sachiko Ozawa, University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy

“We estimated that substandard [poor-quality] and falsified antimalarials are responsible for US$20.9 million (35 per cent) of US$59.6 million in malaria costs in Kinshasa Province and $130 million (43 per cent) of US$301 million in malaria costs in the Katanga region annually,” says the study in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which was published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene last week (21 January).

In Uganda, the researchers estimated that substandard and fake antimalarials account for U$31 million, or eight per cent cost of the annual burden of malaria among children under five years who sought care, according to the findings published in the Malaria Journal this month (9 January). The costs include those to be paid by government, out-of-pocket payment for patients and productivity losses.

Ozawa tells SciDev.Net that in their estimations, if antimalarial resistance occurs because of fake and poor-quality drugs, there could be seven per cent more Ugandan children under five dying from malaria each year.

“The public can hold the health system accountable to deliver good-quality medicines,” Ozawa says.

The model was used to create a virtual population of children with varying characteristics such as socioeconomic status and probability of getting malaria.

The authors then simulated what happens when children get sick with malaria and seek care, with assumptions such as hospitalisations, medication use and the impact of substandard and falsified antimalarials.

According to Ozawa, although the model has limitations such as gaps in the literature on the real cost of substandard and fake medicines to patients, their families and the government, similar results could be generated in other African countries.

Patrick Ogwang’, a senior lecturer in pharmacy at the Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda, agrees with the findings of the studies.

According to Ogwang’, poor-quality and fake antimalarias lead to malaria complications.

He adds that private clinics are more likely to have poor quality and fake antimalarials than government-owned facilities.

“Going to government-owned hospitals for malaria treatment is a sure way of curbing the menace of using substandard and falsified antimalarials,” he tells SciDev.Net.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

[1] Sachiko Ozawa and others Modelling the economic impact of substandard and falsified antimalarials in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 21 January 2019).

[2] Sachiko Ozawa and others Development of an agent-based model to assess the impact of substandard and falsified anti-malarials: Uganda case study (Malaria Journal, 9 January 2019)