08/08/19

Used malaria test kits ‘aid drug resistance testing’

By: Evelyn Otieno

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

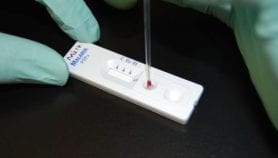

[NAIROBI] Test kits that have been used to rapidly identify malaria parasites could be used to assess resistance to antimalarials, a study shows.

The WHO recommends that countries evaluate the effectiveness of medicines for treating malaria — called artemisinin combination therapy — every two to three years but logistical issues threaten the achievement of this goal in Sub-Saharan Africa, forcing experts to consider other strategies to complement such effectiveness studies.

Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounted for 66 per cent of the 276 million rapid diagnostic test sales worldwide in 2017, says the WHO’s malaria report released in 2018. The report adds that rapid diagnostic tests formed 40 per cent of all malaria tests in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2010 but in 2017 the figure rose to 75 per cent.

“The point is to keep an eye on the parasite, and catch development of resistance as early as possible.”

Sidsel Nag, University of Copenhagen

“We wanted to explore the possibility of systematically collecting rapid diagnostic tests after diagnosis and then using them for routine screening for mutations [changes in the structure of genes] in the parasites that cause resistance to antimalarials,” says Sidsel Nag, lead author of the study and a biologist at the Department of Immunology and Microbiology, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. “The point is to keep an eye on the parasite, and catch development of resistance as early as possible.”

According to the study published in the Malaria Journal last month (26 July), researchers sampled 2,184 rapid diagnostic tests that had tested positive for malaria between May 2014 and April 2017 in a health centre in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. The 1,390 kits that were found to be positive for the genetic make-up of malaria-causing parasites were further analysed for evidence that could predict the presence of antimalarial resistance.

About 74 per cent of the positive rapid diagnostic tests had the genetic make-up of the parasites that cause malaria, with the genes for causing antimalarial resistance varying from 13 to 87 per cent after analyses, the findings show.

Africa alone had 92 per cent of the 219 million cases of malaria that occurred in 2017, the WHO says. “Malaria is still a large burden in Africa, and resistance will cause resurgence in malaria cases and fatalities, if left unhandled,” explains Nag. “If we are not treating the infections effectively, the patients merely contribute to spreading more parasites, and the parasites develop more tolerance, eventually resulting in resistance toward the applied antimalarials.”

Simon Kariuki, head of the malaria programme at the Kenya Medical Research Institute’s Centre for Global Health Research, tells SciDev.Net that assessing the effectiveness of antimalarials in Africa every two to three years is not possible because of inadequate infrastructure and skills.“Rapid diagnostic tests will be useful in the surveillance of antimalarial drug resistance. Instead of collecting blood samples from people during surveys, which can be expensive, this study shows that you can use rapid diagnostic tests. This cuts down the cost of conducting surveillance,” he says.

It is important to properly store used rapid diagnostic tests to avoid compromising their quality, Kariuki adds.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

Sidsel Nag and others Proof of concept: used malaria rapid diagnostic tests applied for parallel sequencing for surveillance of molecular markers of anti-malarial resistance in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau during 2014–2017 (Malaria Journal, 26 July 2019)