By: Adole Abutu

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[LAGOS] Efforts to curb the serious malaria problem in Nigeria could become more challenging due to the rampant use of sub-standard medicines, a new study suggests.

The study conducted in Enugu metropolis, south-east Nigeria, by researchers from University of Nigeria and UK-based London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), found 9.2 per cent of 3,024 of antimalarias as being of poor standard.

Researchers say patients risk not receiving the correct treatment dose, potentially contributing to the development of resistance to the main drug used to treat malaria.

“Our study highlights the need for increased pharmacovigilance and greater regulatory control on local ACT production, importation, drug storage and provision.”

Obinna Onwujekwe, University of Nigeria

According to a statement from the LSHTM, malaria attacks 48 million people in Nigeria a year, resulting in 180,000 deaths, thus making the country bear the brunt of the disease more than any other in the world.

In 2013, the researchers bought antimalarials in Enugu, a city with about 3.3 million people, from 421 outlets such as pharmacies and public health facilities by using mystery clients who pretended to be sick of malaria or whotold vendors that they would be assessing the quality of the medicines, says the study published in PLOS One on 27 May.

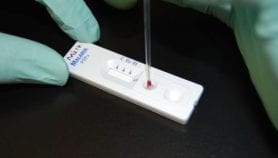

Harparkash Kaur, the study’s lead author and drug quality expert at LSHTM, tellsSciDev.Net that artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) is the first line drug endorsed by the WHO to treat malaria, and that there is no independent information on the quality of these drugs in Nigeria.

“The study sample area is small as Nigeria is a big country with regulations controlled at state level, but our study findings from Enugu can be completely generalised to southeast and south-south Nigeria — home to more than 60 million people,” Kaur adds.

The researchers classified the medicines “as acceptable quality, falsified (fake drugs which do not contain the stated active pharmaceutical ingredient or API), sub-standard (which contain inadequate amounts of the active ingredients), or degraded,” according to the LSHTM statement.

The studyshows after analysing the antimalarials 9.2 per cent of them were of poor quality, 1.2 per centwere falsified, 1.3 per cent were degraded, and 6.8 per centwere substandard in one or more of the APIs.

Study co-author Obinna Onwujekwe, a professor of medicine at the University of Nigeria, Enugu campus, says: “Our study highlights the need for increased pharmacovigilance and greater regulatory control on local ACT production, importation, drug storage and provision. The manufacturers of fake drugs need to be found and shut down. The manufacturers of substandard drugs need their factory processes strengthened to produce quality assured drugs.”

Bernard Akpa, a pharmacist based in Makurdi, north-central Nigeria, said the finding could be the result of the absence of a certified channel for bringing drugs into pharmacies in Nigeria.Rotimi Akereye, a general medical practitioner with the Bingham University Teaching Hospital in Nigeria, adds that the development could be responsible for the increasing resistance to antimalarials noticed among Nigerians.

“Prescribed drugs are in most cases not working and this has led to the abuse of antibiotics which are being introduced, thinking that the illness is no longer malaria but other types of fever,” Akerele says.

This article has been produced by SciDev.Net's sub-Saharan Africa desk.