31/08/20

Existing tools ‘fail to halt new malaria cases’

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[NAIROBI] Implementing currently available tools for fighting malaria reduces the disease’s existing cases by 85 per cent but it is not enough to interrupt its transmission, a study says.

With the 2019 World Malaria Report estimating the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region to be having 93 per cent of the 228 million cases of malaria globally in 2018, eliminating the disease in Africa is a priority of the WHO and partners including governments.

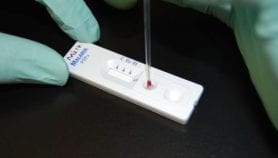

The WHO encourages the use of tools such as insecticide-treated mosquito nets, indoor spraying with residual insecticides and antimalarial drugs administration.

“The Magude project revealed that an intensive implementation of currently available tools recommended by the WHO can achieve major reductions in malaria transmission.”

Beatriz Galatas, Barcelona Institute for Global Health

However, the study that was conducted in Southern Mozambique found that while malaria burden reduced with efforts such as building on an enhanced surveillance system and providing two rounds of mass drug administration interventions, it fell short of interrupting the transmission of the parasite that causes malaria: Plasmodium falciparum.

“The Magude [District] project was designed to evaluate the possibility of malaria elimination using the prevention and treatment tools currently available, in a malaria endemic district of Southern Mozambique,” says Beatriz Galatas, the lead author of the study published in PLOS Medicine this month (14 August).

The study project took place from 2015 to 2018 in the district of Magude, a rural setting where 48,448 people live in 10,965 households.

It was divided into two phases. The first phase, from August 2015 to August 2017, was aimed at reducing the number of malaria cases to zero while the second phase, from September 2017 to June 2018, was to sustain the gains achieved for a period of one year after phase one.

The findings show that the implementation of a package of interventions in areas of Sub-Saharan Africa cannot interrupt malaria transmission.

“The Magude project revealed that an intensive implementation of currently available tools recommended by the WHO can achieve major reductions in malaria burden of disease, which is a necessary step on the pathway towards elimination,” adds Galatas, an epidemiologist at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health.

According to the study, the proportion of people with malaria reduced by about 85 per cent while the proportion with new malaria cases reduced by about 66 per cent.

She tells SciDev.Net that the Magude project should be viewed as an essential step of the pathway towards elimination of Malaria.

“At a time when the global fight against malaria is plateauing at an unacceptably high level, with over 200 million cases and an excess of 400,000 deaths, a large majority of them among African children and women, our global public health priority has to focus on reducing disease and death, particularly among the most vulnerable populations,” adds Galatas. “This should be viewed as an essential step of the pathway towards elimination.”

Eliningaya Kweka, an associate research professor of medical entomology at Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences in Tanzania, says that although the interventions seemed effective in reducing malaria cases, there was a very short limited data of pre-intervention, which might have weakened the accuracy of the comparison of the data before and after the interventions.“The intervention cover was low, which left some parasite pools untreated and became source of infections in the community,” he says.

Kweka adds that the study findings have a wider promising impact in Sub-Saharan Africa for malaria control and elimination but calls for the need to consider other malaria control interventions.

“Improving of house quality in rural Africa should be a campaign in all intervention programmes,” explains Kweka.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

Beatriz Galatas and others A multiphase program for malaria elimination in southern Mozambique (the Magude project): A before-after study (PLOS MEDICINE, 14 August 2020)