By: Cobi Smith

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[LONDON] Preventative malaria treatment could improve schoolchildren’s performance in endemic areas, a study suggests.

The research was presented at the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine’s conference in London, United Kingdom, last week (14 September).

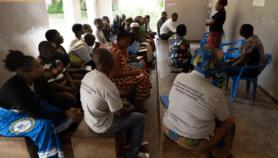

Benson Estambale, director of the Institute of Tropical and Infectious Diseases at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, investigated whether giving preventative antimalarial drugs to primary schoolchildren improved their educational performance.

More than 6000 students from 30 schools in the Bondo district of West Kenya were administered antimalarial drugs three times during the 2005–2006 academic year.

Treatment cut the students’ risk of malaria parasite infection by more than a third, as well as reducing anaemia. Researchers found that treated children performed better in cognitive tests and also did slightly better in school exams.

Previous studies of malaria-infected regions indicate that up to 50 per cent of all preventable absenteeism in schools is due to malaria, and the research team found that a number of people wanted to have their children treated for malaria because of absenteeism, Estambale told delegates.

“[Preventative treatment] is very much recommended for pregnant women and has been tried in infants and young children, but nothing had been done in children over five years of age,” he said.

Estembale said the Kenyan Ministry of Education had expressed interest in the study and the researchers hope it could lead to the introduction of routine preventative therapy for schoolchildren, as the government has done with de-worming.

“De-worming has become official policy in the country and school health programs are now de-worming the children twice in a year to remove all the intestinal worms that could impact negatively on children’s performance in schools,” Estambale said.

Nick White, head of tropical medicine at Mahidol University in Thailand and a WHO advisor, said the results were exciting but future research should further examine the exact relationship between drug efficacy and educational performance, and whether the findings applied in other malaria-affected regions.

Further studies are planned in Kenya and Senegal, and Estambale also hopes to gain partners in Asia and South America.