By: Scovian Lillian

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Climate change-induced food insecurity is worsening the plight of smallholders, writes Scovian Lillian.

Anna Surora, a middle-aged subsistence farmer from Kajiado county, in southwest Kenya, says that life has been a struggle in this harsh environment for decades but things were never as bad as they are now.

Surora has seen her beans, maize and sweet potato yields dwindle over the years because of low rainfall but the years 2020 and 2021 have been the worst, leaving her and many households in the area dependent on relief food from the Kenyan government.

In recent years, smallholder farmers such as Surora in this region predominantly inhabited by the Maasai community, well known for pastoralism and mixed farming, have been hardest hit with droughts and resulting food insecurity.

The smallholders have helplessly watched their crops dry and shrivel to nothing while livestock waste away to bones and fall dead amid shocks of climate change characterised by droughts.

A Kenyan Maasai pastoralist searching for pasture after drought ravaged Kajiado county last year. Credit: Michael Opiyo.

Besides low rainfall, the situation was worsened by desert locust infestations.

“They came like dust, wind, and fire in April last year,” says Surora. “They ate all the grass that is pasture for our livestock and when the grass got finished, they ate all leaves on trees. We depend on meat for food, so that was food lost. In this area there is not enough rainfall to sustain farming.”.

The spread of COVID-19 since 2020 has led to a delay in the supply of farm inputs to her area. With late planting, she says, the little rain there was did not help her crops.

“I sold my cows and sheep to embrace farming using drip irrigation. I did not want them to die from drought.”

Haron Suyianka, Kenya’s Kajiado West county

”The droughts destroyed my food crops. I had planted maize, beans, sweet potatoes and tomatoes but all were destroyed by prolonged drought,” she tells SciDev.Net, adding that women and children suffered in particular.

Coping with the drought

With poor crop yields and no pasture, Surora decided to sell her livestock to get money to buy food. Unfortunately, she lost most of them before selling. “I had 100 sheep but after locusts invaded this village, coupled with the raging droughts, I remained with only ten sheep as the rest died due to lack of pasture,” she explains.

Kenya’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation categorises Kajiado county as a semi-arid region where livestock rearing and crop farming are the main economic activities. Agricultural activities are mainly done along rivers and springs because of the long droughts in the area.

Hotter climate, according to the UN Environment Programme, can lead to “more damaging locust swarms, leaving Africa disproportionately affected”.

Elizabeth Oruma, a resident of Olasiti village in Kajiado West, says that droughts caused her massive yield losses.

”I have been practicing mixed farming since the year 2017 for home consumption but whenever there is surplus I could sell to neighbours,” she explains. “I could sell ten to 15 bags of maize whenever there was surplus production. In the year 2019, I incurred massive losses due to drought. It destroyed food and particularly maize and beans and I had very little harvest.”

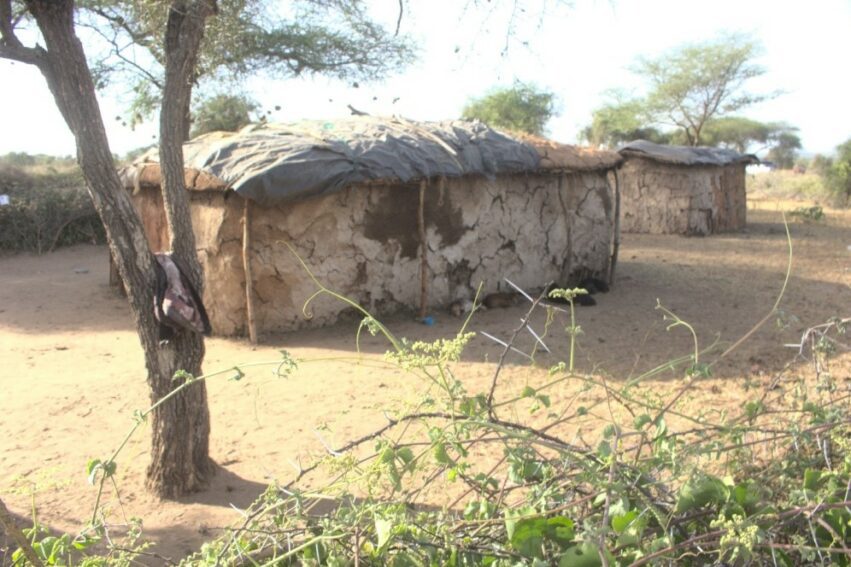

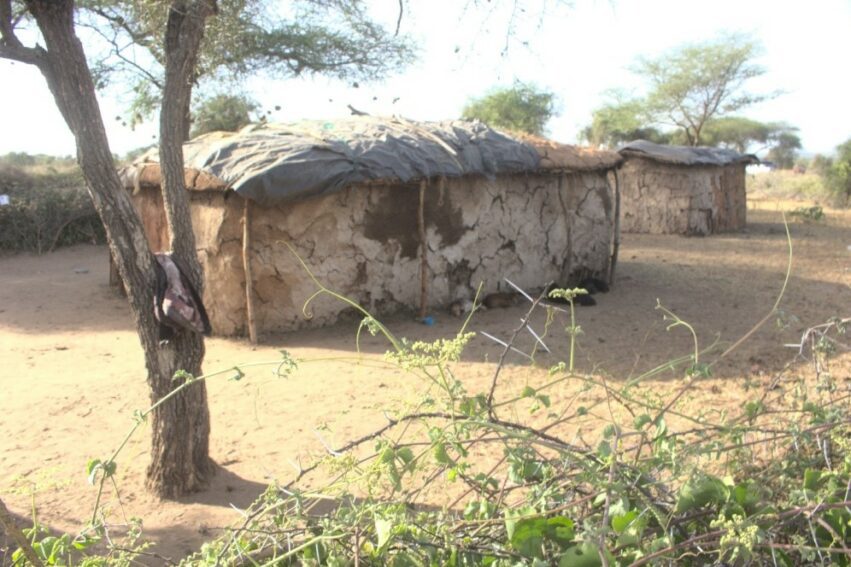

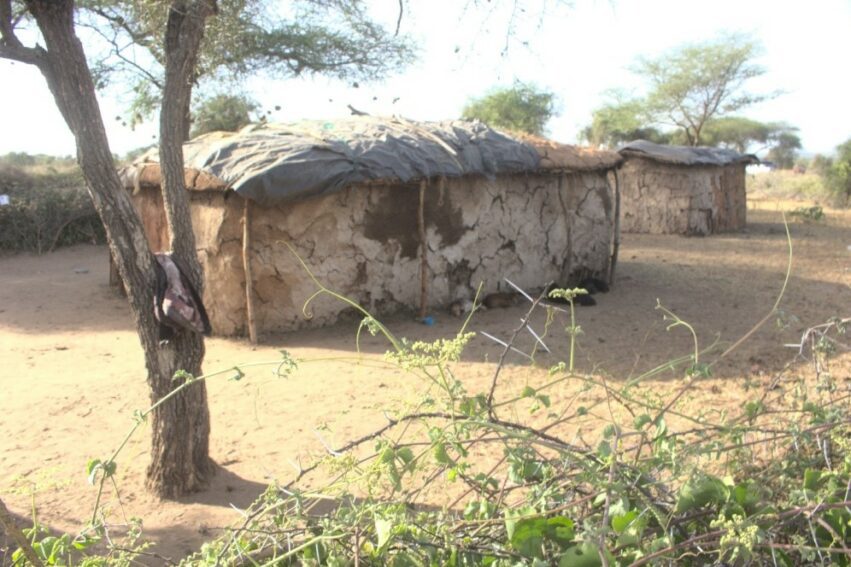

Deserted traditional Maasai manyatta home after owners moved with their livestock in search of pasture. Credit: Michael Opiyo.

But Oruma adds that she continued crop farming despite the drought. She tells SciDev.Net: “Women are always food providers in homes. It is very important that they step up and embrace resilience for food production despite the adverse effects of climate change to ensure that children don’t go hungry.

“Women and children are always the most affected by acute drought. It becomes even harder for women as they should provide [food for the family]. Women have no choice but to keep trying using irrigation.”

According to Nelly Suyianka, a smallholder at Naserian village in Kenya’s Kajiado West county, the worst droughts are usually experienced during January, February and March.

The weather outlook by the Kenya Meteorological Department in 2021 showed that October, November and December were short of rainfall in Kajiado county.

Together with her husband Haron Suyianka, she practises mixed farming. They plant various kinds of fruits, vegetables, maize, sweet potatoes, and French beans.

Although the Maasai community feeds mostly on meat and milk from their livestock, which includes cows, sheep and goats, Haron sold his livestock in 2020 because of the drought.

“I sold my cows and sheep to embrace farming using drip irrigation. I did not want them to die from drought,” he says. “Towards the end of last year, I experienced losses on my farm when the drought hit. Almost 1,000 birds invaded my farm and ate my maize since there was no other food for them.”

Suyianka, who is a retired pastor, provides food solutions to women for their children by giving them jobs of planting and harvesting. The women help on his five-acre piece of land by planting and carefully harvesting French beans and he shares the produce with them.

Devastating impact of drought in Kajiado East in Kenya. Credit: Michael Opiyo.

No end in sight

In November 2021, a bulletin by the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) on Kajiado county warned that rain-fed crop production was likely to fail due to poor rains throughout the region, and livestock was emaciated due to lack of forage. The terms of trade were declining steadily indicating worsening household food purchasing power.

It also warned that the number of children at risk of malnutrition was increasing each month and about five per cent of the households were consuming a poor diet in terms of food items and frequency of consumption.

The bulletin further indicated that many households are not getting enough food, have limited dietary diversity and are malnourished. This was evident between May and November 2021.

James Oduor, the chief executive officer of the National Drought Management Authority in Kenya, says that by December last year 56,000 residents of Kajiado county were affected by drought, adding that the number is likely to increase by February this year.

“At the larger landscape and national level, investments are needed to ensure constant water supply including dams and water pans.”

Jemimah Njuki, International Food Policy Research Institute

According to Oduor those affected received relief food from the government in October last year as a short-term intervention.

“Health and nutrition for children under five and lactating mothers become a problem whenever drought hits and the issue of malnutrition due to lack of food happens,” he explains.

Richard Munang, the Africa regional climate change coordinator at the UN Environment Programme, says that climate change trends are no longer an abstract issue.

“Africa, as a region that is already heating up twice as fast as the rest of the globe, faces a more dire prognosis,” he explains.

“This state of emergency has also been a glaring anomaly for the region for quite some time now. From a 20 per cent decline in precipitation to a 20 per cent increase in storm intensity, to an eight per cent increase in arid and semi-arid lands, and an up to 50 per cent drop in rain-fed agriculture potential, the writing of the climate emergency has been clear and consistent.”

Munang explains that in Kenya, for instance, the famine frequency has been increasing — from one famine in 20 years between the 60s and 80s to a famine almost every year from the mid-2000s.

“The risks projected for 2022 by the Famine Early Warning Systems Network – is not a sudden occurrence for isolated regions of Africa or indeed counties in Kenya, but within the long-term trend of the changing climate that has been going on for a longer time,” he adds.

Dry, hardened bare earth as a result of prolonged droughts in Kajiado county, Kenya. Credit: Michael Opiyo

Needed interventions

Jemimah Njuki, director for Africa at the International Food Policy Research Institute, says that climate change is impacting smallholders and livestock keepers in different ways and actions to curb it are needed at different levels.

She tells SciDev.Net: “At the farmer and livestock keeper levels, climate-smart innovations including the planting of trees and shrubs, drought-tolerant crops including new varieties that have been developed to thrive in dry and water stress conditions, land and herd management to reduce overgrazing all can help livestock farmers manage the impacts of climate change.

“At the larger landscape and national level, investments are needed to ensure constant water supply including dams and water pans, and access and availability of climate-smart innovations.”She calls for increased availability of markets for livestock keepers during drought to reduce the loss of animals, and a market-based livestock restocking programme after drought.

Disclaimer: The Social Impact Reporting Initiative sponsored Scovian Lillian in producing this story.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.