By: Samuel Hinneh

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[ACCRA] Ghanaian scientists have designed beads to educate mothers to accurately monitor children’s respiratory rates and diagnose signs of pneumonia.

According to the WHO, in 2015 pneumonia accounted for the 16 per cent of the deaths of children younger than five years old, with Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia bearing the greatest burden of the disease among children.

Children with pneumonia have a range of symptoms such as fever, fast breathing, cough and sometimes difficulty in breathing.

“Most of the mothers were able to accurately count their child’s respiratory rate using the beads and recognise other signs of pneumonia.”

Daniel Ansong, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana

The lead researcher, Daniel Ansong, says that the project seeks to evaluate the socio-cultural understanding of pneumonia and the level of confidence among women in counting respiratory rates and detecting signs of pneumonia.

A multidisciplinary research team and a local beads designer created the beads using materials such as twisted nylon twine and heat-pressed polyester flags. The team sought the opinions of women and child health experts to help refine the beads.

The beads are similar to the ones used in the local setting for religious purposes among the Catholics and Moslems, thus making them culturally acceptable, explains Ansong, a lecturer at the School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana.

Ansong adds that the project was implemented with US$10,000 funding from the Danish International Development Agency through the Building Stronger Universities initiative.

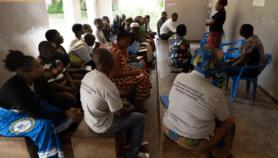

The team piloted the concept by recruiting 100 postpartum women attending child welfare clinics at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH), Ghana.

The team also used videos to educate the mothers on use of the beads and supplied one-minute sand timers to help the users count respiratory rates, said Ansong, in an interview with SciDev.Net last month (30 May).

The intervention was implemented from July to September 2016, with assessments at four and eight weeks after the training.

“Most of the mothers were able to count accurately their child’s respiratory rate using the beads and recognise other signs of pneumonia,” Ansong said.

Evans Xorse Amuzu, a research assistant at the KATH who was involved in the project, adds, “After eight weeks, about 85 per cent of the mothers accurately counted respiratory rates using the beads.”

Francis Adjei Osei, a project manager at the Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research, KNUST, who worked on the project, says that the interpretation of the colour coding used to design the beads is similar to that of traffic light.

The beads made of different colours are operated on the assumption that if a mother is able to count the respiratory rate of a child together with the beads and it falls in the green zone for a particular age then it’s normal. If the count falls within the yellow then it is above normal and the mother needs to count again and observe.

Should the respiratory rate count falls within the red zone, the mother needs to count again the child’s respiratory rate and if after several counts it remains in the red zone, the mother needs to visit the hospital. The ambulance sign in the design tells the mother what needs to be done, which is taking the child to hospital after the count falls in the red beads zone repeatedly.

“Red which communicates ‘stop’ (danger) represents a dangerous respiratory count in our design. Green which communicates ‘do’ (no danger) represents a good respiratory count. Yellow, which communicates caution, represents a potentially dangerous respiratory count that requires more regular monitoring,” he says.

The investigators intend to scale up the intervention to enable them to establish the effectiveness of the intervention in a larger population.Kofi Mensah Boateng, a medical officer at Manna Mission Hospital in Accra, Ghana, tells SciDev.Net that the use of the beads to diagnose pneumonia could help reduce the workload of clinicians in managing pneumonia as mothers send only children who need care to health facilities, thus offering an ample time for clinicians to attend to critically ill children.

According to Boateng, the initiative should be incorporated into the World Pneumonia Day annually held on 12 November and is celebrated in Ghana to help educate new mothers and help fight the disease.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.