By: Julia Makinde

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

New polio cases in Nigeria have prompted the use of unusual ways to eradicate the disease, writes Julia Makinde.

Borno state, located in north-eastern Nigeria, was previously known for its wealth of livestock and fishery products. But the Nigerian state that shares boundaries with Cameroon, Chad and Niger is now the unlikely battle ground for Nigeria’s fight against two formidable enemies: polio and Boko Haram.

Major polio eradication setback

Considering that there were no reported cases of Polio in Nigeria from July 2014 to July 2016 the discovery of four new cases of wild polio in August this year has been regarded as a major setback in Nigeria’s attempt to become polio-free. [1] This development places the country back on the list of three countries that are still attempting to eradicate the virus, the others being Afghanistan and Pakistan. Spanning about 93,000 square kilometres and 27 local government areas, Borno State is also the epicentre of the humanitarian crisis precipitated by the activities of the Boko Haram sect in Nigeria.

“Attaining complete eradication against the backdrop of dire security and humanitarian conditions will be particularly challenging.”

Gbenga Olayiwole

Assessments by both the International Organisation for Migration, Nigeria and the National Emergency Management Agency indicate that over 2 million people have been displaced since the onset of the insurgency, including 700,000 people being displaced in 2015 alone.[2] It is worth noting that the Nigerian internally displaced persons (IDP) population is skewed towards women and children, many of whom were born in captivity or during the Boko Haram crises. Husbands and fathers have either been killed or drafted to join the sectarian army.

Polio eradication challenges and efforts

The recent discovery of polio cases in territories occupied by displaced persons can hardly be considered a coincidence. Monguno, Gwoza and Jere local government areas located in the north, south and central districts of Borno state respectively have only recently been recaptured by government troops after years of being occupied by members of the Boko Haram sect. Residents of these local government areas have been subjected to severe rationing of meagre supplies of food and water whilst in captivity. The military-led liberation of these areas have enabled access, heralding the discovery of these new wild-type polio cases and the subsequent public health campaign to bring the country back on track towards achieving its polio eradication goals.

“Attaining complete eradication against the backdrop of dire security and humanitarian conditions will be particularly challenging,” says Gbenga Olayiwole, a public health and polio communications consultant based in Nigeria who has worked on the frontline of the country’s polio eradication initiative for over four years.

The unique circumstance around the re-emergence of polio is forcing a rethink of approaches to surveillance and the strategies deployed to ensure adequate vaccine coverage.

Coded mapping of local government areas in territories affected by the Boko Haram crises in the order of accessibility has so far helped stratify the immunisation drive. According to Olayiwole, Borno state, in September, set a target to immunise 3.2 million children under the age of five. The first phase of this effort targeting 14 of the 27 local government areas has already commenced with the deployment of over 1,500 vaccination personnel. The risk of access poses a major challenge to this effort.A second zoning approach further identifies regions that cannot be accessed by healthcare personnel without armed security operatives drafted from the army or the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) to administer the vaccine. Although liberated, these areas are still considered to be in a relatively fragile state of security. Chibok local government area is home to the school that had 21 girls recently released from Boko Haram captivity.

“Attaining complete eradication against the backdrop of dire security and humanitarian conditions will be particularly challenging.”

Gbenga Olayiwole

Several of the school’s wards are currently only accessible with assistance from the CJTF. A significant strategy has been to merge streams of expertise in order to get the vaccines where they need to be. The largest civilian clinic in Bama local government area is currently run by the Nigerian Air Force, enabling them to double as security and immunisation agents. Members of the CJTF have also been trained through an informal knowledge transfer process to carry out immunisations.

“Getting the vaccines and personnel to the field locations is only a part of the exercise,” says Gbenga. It is easy to assume that personnel are welcomed with open arms once in the field. This is simply not the case. Recently liberated communities are now shells of their previous selves as the individuals live within protected camps in fear of reprisal attacks or in rundown structures in their old communities.

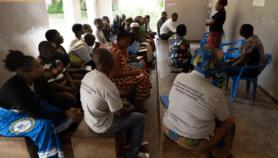

The Muna IDP camp in Borno state.

Source: Gbenga Olayiwole

Understandably, the arrival of the field agents can be viewed with suspicion. To circumvent this agents usually arrive armed with the polio vaccines and “sugar packets” relief supplies containing items for basic personal care and some food, to endear trust and encourage vaccine uptake. The relief materials are always welcomed and are rationed by administering ink stamps on the fingers of children who have received them along with the vaccines. Where security is a major concern, field agents can employ a “hit and run” approach in which agents aim to arrive and deliver the vaccines to as many children as they can within a short time before rapidly exiting the community. Admittedly the latter approach may not always allow for adequate assessment of numbers, as such it is usually only deployed where absolutely necessary.

Children at an Islamiya school in Borno where field agents adopted a “hit and run” approach to vaccination.

Source: Gbenga Olayiwole

Understanding dynamics of migration

The journey towards achieving the complete eradication of polio requires a critical understanding of the dynamics of IDP migration. Although it sits at the epicentre of the current crises, Borno is not the only Nigerian state affected by the activities of Boko Haram insurgents.

Most IDPs resulting from Boko Haram insurgency currently reside in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states. Also, some Nigerians have reportedly sought refuge in neighbouring countries such as Cameroon, Chad and Niger, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

Integrated mapping of IDP camps and known refugee settlements against the zonal coding information on the security states of the various local government areas will allow for the prediction of the migratory routes that these individuals are likely to take in event of an insurgent attack. This information will enable adequate distribution of resources and population monitoring.

Figure 1: Estimated numbers of individuals displaced by the insurgency in Nigeria.

Source: IDMC 2016

Figure 2: Estimated numbers of refugees in neighbouring countries.

Source: UNHCR, October 2016

It has been about two months since the first of the four new cases of Polio was uncovered. There appears to be an enormous effort on the part of all concerned to bring the country back on track towards its goal to attain complete eradication of polio. The unconventional methods being deployed to achieve this are a testament to the unique situation that the country faces. Dealing decisively with the insurgency will bring considerable resolution to some of the problems associated with access and adequate surveillance.

Until this happens, continuing with due vigilance might be the only way that meaningful progress can be made.

Julia Makinde is a research scientist in the Department of Virology at Imperial College London. She tweets at @quixotic_me

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Sub-Saharan Africa English desk.

References

[1] Government of Nigeria reports 2 wild polio cases, first since July 2014 (World Health Organisation, 11 August 2016)

[2] Global displacement database (The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre [IDMC], 2016)