31/03/22

Urgent need for farm climate adaptation cash: report

By: Laura Owings

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

This article is supported by the CASA programme.

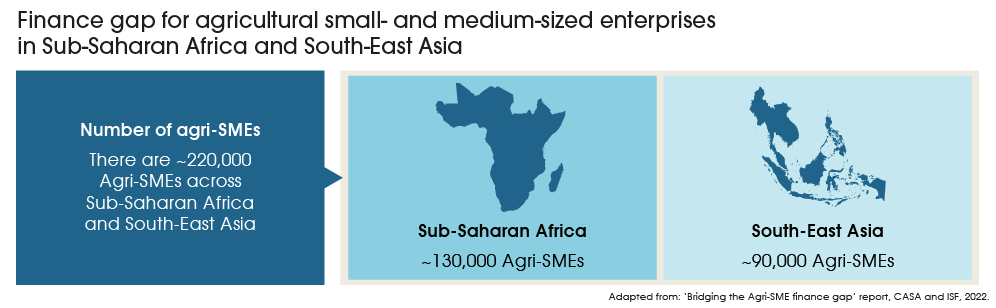

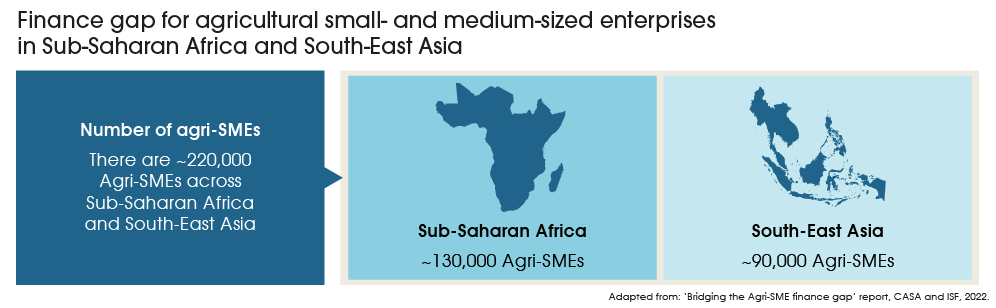

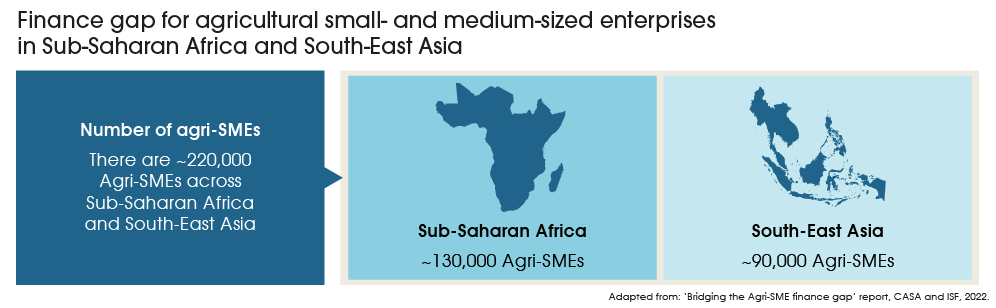

Small farms and agricultural firms in Sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia are facing a billion dollar cash black hole for climate change adaptation, a report says.

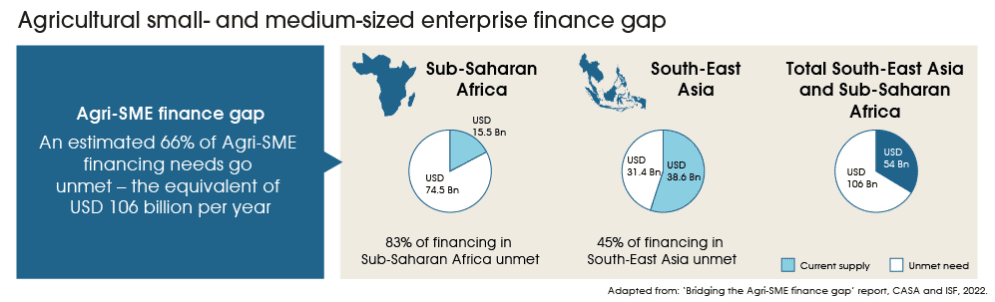

Overall there is a gap of US$106 billion in available investment in agricultural small- and medium-sized enterprises (agri-SME) ranging from farms, to rice millers and agricultural data firms, according to the report, entitled The state of the agri-SME sector – Bridging the finance gap.

“Not only is there a gap for traditional financing needs for agri-SMEs in these regions, but there is also a big gap in the need to mitigate risk of climate change, with essentially no money going toward these needs,” explains report author Jérôme van Innis, a senior manager at the South African strategic and financial advisory group ISF Advisors, which produced the report alongside the Commercial Agriculture for Smallholders and Agribusiness (CASA) programme, which supported this article and involves CABI, the parent organization of SciDev.Net.

According to the report, the cash is needed by small firms operating in the agriculture space to finance day-to-day operations, but also to fund investments and adapt to changes brought about by global heating.

Outlining priorities for investors and policymakers to support the sector, the report calls for the urgent mobilisation of climate adaptation funding for agri-SMEs. However, achieving this requires a system of measurements that identify opportunities for adaptation investment, and government policies that support a pipeline of agri-SME innovation.

Investment in agriculture is an effective poverty-reduction tool, according to global charity Oxfam, while also improving food security and economic development.

But without a system that can identify measurable adaptation outcomes, investors will struggle to support small-scale farmers to grow their businesses, say specialists.

Absence of climate finance

Within this overall picture, the report shows there is an “absence of any major flows of climate finance for agri-SMEs relative to the known dimensions of the climate crisis”.

Globally, only 1.7 per cent of global climate finance, or about US$10 billion, is available to small-scale agriculture, according to the analysis and advisory organisation Climate Policy Initiative. Over 95 per cent of that is provided from public sources and earmarked largely for efforts to curb climate change, rather than adapt to it.

“Certain things need to be done to essentially put in place products and services to help these SMEs mitigate and adapt to climate change from the highest levels all the way down to local investors,” says Van Innis.

To address this part of the financing gap, the report calls for new, foundational infrastructure to be established in the next three to five years to increase the financing available to agri-SMEs for climate-related investments.

Among these is the development of common methods that define climate adaptation and mitigation in agri-SMEs. Without this, Van Innis says, investors are at risk of ‘greenwashing’, or attempting to pivot towards climate finance without a clear understanding of how to do so.

“If we’re not linking up to specific metrics, what are we tracking?” he asks. “It’s a tenuous link and tenuous tracking of adaptation and mitigation impacts unless all actors are talking the same language.”

Metrics for adaptation

A set of commonly agreed upon measurements, or metrics, could provide this clarity for climate adaptation finance. “Metrics provide an understanding of what you’ll get from interventions, which can be used to establish cost effectiveness,” says Ken Chomitz, chief economist at the Global Innovation Fund (GIF), a non-profit investment fund headquartered in the United Kingdom.

Unlike mitigation, which has tangible elements that can be measured, such as a reduction of carbon dioxide emissions, adaptation lacks a universal target. Much of this is due to the context-specific nature of adaptation — what works in one place may not work elsewhere.

Take, for example, an innovation aimed at increasing maize yields in drought-prone areas. The project could use drought-resilient seeds, irrigation, or soil management, and be held against a single metric of maize yield in low rainfall years, the report proposes.

“This could be useful for learning which option is the best to address a particular problem, but does it boost the smallholder farmer’s resilience?” asks Chomitz.

“The metric we propose focuses on what aspects of poverty are resistant to climate shocks and how good are we at protecting people against shocks which might send them into a poverty trap.”

Progress toward an accepted adaptation metric, however, will take time. “Any standard setting system will take years to fully realise, but we’re moving in the right direction,” Chomitz says.

Creating a pipeline

While metrics can help attract adaptation investment for agri-SMEs, governments must also play a part, says Maria Tapia, programme lead for climate finance at the Global Centre on Adaptation.

She recommends creating a stable regulatory environment, as well as tax incentives and concessional financing, or cheap financing around adaptation innovations.

“Government must make a clear climate commitment with policy that includes an adaptation plan and investment strategy, and which prioritises certain … sector projects,” she says. “By first putting its own financing into that plan, and then calling for international cooperation to co-finance, governments can attract the private sector.”

In this way, governments also create a pipeline of agri-SME innovations that can be aggregated — bundled into a single project — and scaled. “Many of these projects are too small to attract big investors. With national climate funds, they can be repackaged and sold to private investors in a way that makes them more attractive,” she says.This collaborative view of agri-SME financing is one Van Innis hopes the report can generate among the different audiences of investors.

“Let’s be more innovative,” he says. “Let’s develop a common language and pipeline of investment opportunities and make sure these track back to specific performance indicators so we can say ‘yes, our funding is helping SMEs that are achieving impact to adapt and mitigate to climate change’.”

The CASA programme (Commercial Agriculture for Smallholders and Agribusiness) aims to increase global investment in agribusinesses which trade with smallholders in equitable commercial relationships, increasing smallholders’ incomes and climate resilience. Visit www.casaprogramme.com for information and resources.