15/10/21

Students’ future on hold as govts put malls before schools

By: Neena Bhandari

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A “generational catastrophe” looms as governments prioritise opening of malls over schools, resulting in huge learning losses with some 117 million children globally still affected by full school closures due to COVID-19 lockdowns, according to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

“You can’t open shopping malls and keep the schools closed,” UNESCO’s director of division for policies and lifelong learning systems Borhene Chakroun, tells SciDev.Net.

“Governments have to take policy measures now to prevent a generational catastrophe in the future. They should reopen schools as soon as the sanitary situation allows and use closing them as the last resort.”

As of late last month, nine countries — Brunei Darussalam, Fiji, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines and Sri Lanka — in the Asia Pacific region have fully closed their schools due to COVID-19, accounting for 105 million or 10 percent of total students. As many as 51 million are primary school students, according to UNESCO.

But with economies on the brink and with dwindling finances, many countries in the region like Malaysia, Nepal and the Philippines have reopened shopping malls, restaurants and other business establishments while still keeping schools fully closed.

Nine-year-old Altamash is yearning to return to school. “When will school reopen?” is a refrain his mother hears every morning. A student of Grade 4 at Nigam Pratibha Vidhyalaya in Delhi’s eastern suburb of Mayur Vihar in India, he says: “I miss my friends, my teachers, the playground and the school lunch.”

Being cooped up in a two-room home for over 18 months has not been easy for his family of six. Juggling a single device, a mobile phone, among four brothers for attending online classes has been another challenge.

In March 2020, to prevent the spread of COVID-19 many countries began closing schools and moving to remote learning, affecting 1.6 billion learners in developing and developed countries alike.

Schools have had had to switch overnight to distance home-based learning. The Asia Pacific region was largely ill-equipped for this sudden transition. Many countries had to cope with limited infrastructure, costly Internet service and devices, and teachers’ and learners’ readiness with digital skills.

Many families struggled to acquire even a single device. In India, 42 per cent of children between 6 and 13 years reported not using any type of remote learning device during school closures. In Pakistan, 23 per cent of younger children did not have access to any device, according to UNICEF.

“There was a myth, in the first half of 2020, that schools can be replaced by online platforms,” says Chakroun. “Schools have to evolve to cope with hybrid learning and new pedagogical modalities. Online learning modalities have been less effective for primary school children and learning losses have been huge worldwide.”

“There was a myth, in the first half of 2020, that schools can be replaced by online platforms”

Borhene Chakroun, UNESCO*

During school closures, education has been provided through a combination of online classes, printed modules and worksheets, and radio and television lessons.

For Altamash, who loves maths and science and wants to be a doctor when he grows up, it is his elder brothers in Grades 6 and 9 who get priority use of the mobile phone, but they later help him with his lessons. “Reading on a small mobile telephone screen is strenuous unlike on a blackboard. Our teachers made learning fun and students helped each other,” he says.

Lost formative years

Children have missed the hands-on experience of learning and face-to-face engagement with teachers.

Since the onset of the pandemic, schools have been completely closed for an average of 16 weeks in the Asia Pacific region comprising 47 countries. If partial closures by locality or educational level are factored in, the average duration of closures represents 29 weeks across the regions, according to the latest data from UNESCO’s HQ’s Global monitoring of school closures.

During the foundational years of primary school, representing grades one to six, schools are more than just places of learning. They play a huge role in the general cognitive and motor skills development of children.

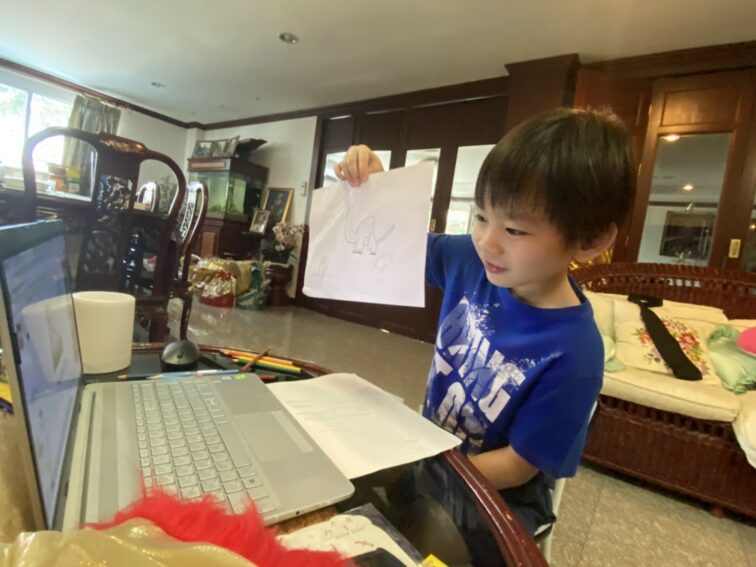

A boy attends his online class. Image credit: ILO/Wanida Losithong (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

It is a place where children learn socio-emotional skills, such as developing friendships with their peers; having access to a library, sports, art and music lessons, excursions to museums, which all add to their general knowledge and understanding of the world. For some, it is also a place where the school meal is the only nutritive meal they get in a day. This overall development and well-being contribute to their learning.

Experts say learning losses at the foundational years of primary schooling have the most long-lasting impact on all aspects of a child’s development.

“If children don’t get the foundational skills in primary school, they can’t reach their full potential in secondary school and in their future prospects. We are yet to understand the full extent of this [school closures] profound negative impact,” says Save the Children Australia’s team lead and senior education advisor Nora Charif Chefchaouni.

Learning poverty compounded

Even before the pandemic, about 60 per cent of children in South Asia were unable to read and understand a simple text at age 10. In addition, 12.5 million children at the primary level were out of school, UNICEF research shows.

This existing learning crisis has been compounded by COVID-19-led school closures, widening inequities in the developing countries of the region.

Chefchaouni tells SciDev.Net: “The quality of education was always a concern. Many children were passing their early grades through automatic promotion. They were not able to read and write in the language of instruction, essential to succeed in secondary school and in life.”

The World Bank and UNESCO coined the concept of Learning Poverty, which means being unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10. A UNESCO study shows that over 100 million children will fall below the minimum proficiency level in reading due to the impact of COVID-19 school closures.

“In Asia, the most affected are children from the poorest socio-economic households, those in rural areas, and ethnic groups in mountainous areas because their mother tongue is not the language of instruction,” says Chefchaouni. “Also, the education system doesn’t provide necessary accommodations to children with disabilities and special needs to fulfill their potential. These existing barriers have been multiplied by the pandemic.”

Home schooling challenges

Besides, in the densely populated countries of Asia, large families sometimes reside in tiny apartments and cramped spaces. Expecting young children to stay focused and engaged in learning, with other distractions in an overcrowded home, can be a challenge.

In Ban Thung neighbourhood of Mae Sot, a city in western Thailand on the border with Myanmar, most Burmese migrant families can have up to 12 people living in a small home, made of bamboo and plastic. In an interview via email through Save the Children, which runs education projects in the refugee camps on the Myanmar-Thailand border, 12-year-old Lin says he is one of the fortunate ones to live in a concrete house with internet access and a computer.

“Many children [in the neighbourhood] have missed out on learning altogether. The teacher sends us weekly homework via Facebook Messenger, but many children don’t have any device or internet,” says Lin.

“The teacher sends us weekly homework via Facebook Messenger, but many children don’t have any device or internet”

Lin, 12-year-old student

His mother, Nay, feels her son is not learning enough and only understands part of the online lessons. “Many children are only copying and have lost all interest in studying. I am educated and able to monitor my son’s progress, but 90 per cent of migrant parents are not educated and cannot help their children with homework,” says Nay via email.

Parents and caregivers have been first line responders to their children’s care and learning during the pandemic. While some parents are very capable of supporting their children, others are unable to teach their children for multitude of reasons, including their own levels of education.

Chefchaouni says, “It is very important to get caregivers, parents and the community engaged because learning doesn’t happen only in schools. Never before in any emergency, we’ve been so focused on parents.”

“This pandemic has brought increased levels of anxiety and stress to the household. Children are like a sponge and they absorb everything. We are encouraging parents to support their children’s learning in a play-based manner because well-being and learning continuity go hand in hand,” she adds.

Risk of permanent dropouts

With the current COVID-19 crisis unfolding, millions of children affected by school closures are now in danger of dropping out of the education system, according to UNICEF.

“We need to ensure that motivation and support from parents and the broader community is there to prevent more children from dropping permanently out of school because they can’t cope on their own when schools reopen,” Chefchaouni tells SciDev.Net.

Primary school kids need more support in study from parents and teachers unlike secondary school children, who may be able to self-study.

Rena Vaja from Victorias in the province of Negros Occidental in the Philippines says, “Children understand lessons better in a face-to-face class. With modules, it’s the parents who are studying. We’re the ones who answer while the children write. I am not even a graduate so I can’t teach like the teacher. I struggle between patience and frustration, but we persevere because we want our children to be educated.”

In most Asian countries, almost every parent’s top priority is to provide quality education to their children.

The 37-year-old mother of four children has a nine-year-old son in Grade 3. She collects the printed modules from his school and she is grateful to the Teacher Fellow, who supports her child’s learning and reading. Teacher Fellows are trained and deployed by the non-profit organisation Teach for the Philippines to teach in high-need public schools.

In an interview through Teach for the Philippines translated from Filipino to English, Vaja says, “I can’t wait for the day when I can walk my child, smartly dressed in a uniform, to school. It would be good to return to proper learning and a routine as nowadays, kids spend all their time chasing birds, biking, playing. Also, it has been difficult to work on the farm and attend to children’s needs and study.”

Most Asian parents see education as a way to ensure their children’s success in life and give them a competitive advantage over their peers in the job market.

Janak Budhathoki wants to ensure that his 11-year-old daughter and six-year-old son get a good education even though he himself has only passed Grade 8.

In a Zoom interview through his daughter’s schoolteacher at Yashodhara Bouddha secondary school in Thainatole in Lalitpur city, Nepal, he says: “Children in primary school are not matured to focus on study at home. They always have some pretext to escape from studying. During regular physical classes, they learn lot of other things too, such as manners and life skills.”

A substantial proportion of students and their parents reported that students learnt significantly less compared to pre-pandemic levels, according to UNICEF research. In Sri Lanka, 69 per cent of parents of primary school children reported that their children were learning “less” or “a lot less”.

Developing better digital content

As school closures continue, advocates say, more digital content should be developed for primary-level learners to make online learning more accessible and equitable.

Microsoft Asia’s regional general manager for education Larry Nelson tells SciDev.Net: “We believe that a student-centred approach that puts the needs of learners first using technology is key to driving improved learning outcomes, accessibility and enabling every child to grow at their own pace.”

Recently, Microsoft has introduced new tools such as Reading Progress to enhance students’ reading skills remotely. “Education institutions should look to adopt a hybrid learning approach, one that delivers a ‘borderless’ learning experience and combines the best of both worlds [physical and online classes], priming children for the digital economy and future of work,” he adds.

Bangladesh has had more than 300 days of school closures. Plan International Bangladesh’s education project manager Mustakima Khanam says: “Many parents have struggled to afford the additional costs of remote education and accessing online classes, such as buying a smart phone or internet costs, while others lack the skills to use smart phones for remote learning.”

Learning losses range from 55 per cent in South Asia, where school closures have been longest, to eight per cent in the Pacific, where schools have mostly stayed open, according to an Asian Development Bank (ADB) report, which examines the costs of pandemic-induced school closures.

“Some families have moved away from urban areas, meaning that children have lost contact with their learning groups (teachers and friends). Many poorer parents have been forced to send their children to work instead of keeping up with their studies,” Khanam tells SciDev.Net via email.

Parents may pull children out of school to work, or they may be forced into early marriage. It is estimated that up to 16 million children are at risk of not returning to school due to economic impacts of COVID-19 alone, according to a Save the Children report.

The adverse financial impact of the pandemic has hit poorer households the most, impacting vulnerable and marginalised learners the hardest.

The present value of students’ future earning reductions is estimated at US$1.25 trillion for developing Asia, equivalent to 5.4 per cent of the region’s GDP in 2020, according to the ADB report.

The economic downturn of the crisis is also adding pressure on national education budgets. Two-thirds of low- and lower-middle-income countries have cut their public education budgets since the start of the pandemic, according to a recent joint report by the World Bank and UNESCO.

“There is a need for pooling resources and capacities and collaborating together to advance learning. We are calling on governments to preserve and increase education budgets and allocate resources in the stimulus packages to adequate wages and skills development of teachers,” Chakroun tells SciDev.Net.

Teachers’ critical guidance role

“Teachers play the scaffolding role not only in learning processes, but also in social integration and well-being of the learners. This is absolutely critical, especially for primary school children, because of the pedagogical process in grades one to six. Empowering teachers will build resilience of the educational system and that will ensure that learning never stops,” Chakroun adds.

UNICEF research found that student-teacher engagement, when regular and reciprocal, is a strong predictor of success in children’s learning, especially for younger students. However, after schools closed, most students had little or no contact with their teachers. In Sri Lankan private primary schools, 52 per cent of teachers reported contacting their students five days a week, but this number dropped to only 8 per cent for teachers from public primary schools.

“The biggest concern is in terms of operationalising learning and supporting teachers. Continuous formative assessment and readiness of teachers to monitor the progress of students, particularly those that are lagging behind, has become very important. Sometimes teachers are more concerned with completing the curriculum, which oftentimes is also loaded,” ADB’s chief of education sector group Brajesh Panth tells SciDev.Net.

“To turn the crisis into an opportunity, ensuring quality of education and removing widening inequities in learning will be vital,” says Panth. Singapore, for example, has reduced and made content more relevant and focused with “Teach Less, Learn More.”

As of mid-September 2021, schools are fully open in 23 countries accounting for 521 million total students, out of which 227 million are primary students. In mid-September 2020, schools were fully open in 27 countries, accounting for 73 million total students, out of which 33 million were primary students. [The total number of students impacted depends on the population size of countries]. Fourteen countries have now partially reopened schools, according to UNESCO.

Many parents are anxious as schools reopen. Elaine Teh has a 10-year-old and an 8-year-old enrolled in the local public school in Penang, Malaysia. She says, “My kids wish to go to school to see their friends in person. I am in a dilemma as having the kids back to school means that they will have proper learning environment, but with COVID-19 cases still sky high I am concerned about exposing them to the risk of contracting the virus.”

Some parents say they have noticed behavioural changes in their children during the lockdowns. Isolated from their peers, they are not as happy and carefree as they were when they were at school. Others are just bored and not motivated to study or play. Yet others say that their children have become irritable and aggressive.

UNESCO is working with partners to develop tools to measure the overall well-being of children. “We have identified three policy measures that can be established. The first is organised through schools to ensure interaction with learners and parents who are critical in this aspect, for example by setting up a WhatsApp communication channel. Second, training teachers on how to cope with their own well-being and how to take into consideration the well-being of the learners. Third, including both physical and psychological well-being in the education financing and resource allocation,” Chakroun tells SciDev.Net.

The pandemic has also resulted in at least two million children under the age of 18 having lost a mother, father, and/or grandparent caregiver who lived in their household as of end of June 2021, according a Lancet study.

“Areas with COVID-19 surges, especially those without sufficient protection from vaccine, will experience surges in numbers of children losing their caregivers. National and local emergency response planning and provision must anticipate and address the needs of children facing orphanhood with its consequent vulnerabilities,” says Susan Hillis, senior technical advisor, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID-19 International task force.

Minimum estimates of primary and/or secondary caregiver loss in South-East Asia is estimated to be 217,700 and that in Western Pacific to be 13,330.

Pacific Island countries

In Pacific Island countries, the impact on education due to the pandemic can be put into two categories, says Michelle Belisle, director of the regional development organisation, Pacific Community’s (SPC) Educational Quality and Assessment Program (EQAP) in Fiji.

“First, many Pacific Island countries have been proactively preparing for the possibility of a closure, even though they have not recorded a single COVID-19 case to date. On the other hand, Papua New Guinea and Fiji have had lengthy disruptions and students are feeling the impact in these countries,” Belisle tells SciDev.Net.

“Many Pacific Island countries have been proactively preparing for the possibility of a closure, even though they have not recorded a single COVID-19 case to date”

Michelle Belisle, Pacific Community’s Educational Quality and Assessment Program

Fiji had closed schools from March to June 2020, then closed them again in April 2021. Primary schools remain closed even now.

“Secondly, many countries rely on technical assistance and in many cases senior officials from Australia and New Zealand, whereby various experts come in and work with ministries of education. In March 2020, these expatriate technical staff were recalled by their governments. So, these countries are short-staffed in key positions and struggled to carry out their day-to-day operations for the last 18 months, which ultimately impacts the children,” she adds.

EQAP is working with countries to try to understand the impact of the last 18 months on primary school students. As part of its literacy and numeracy assessment questionnaires for students in Grades 4 and 6, in 2021 it has included questions to explore what measures have been adopted to provide learning during school closures and how much time away from school have the students experienced.

“This data, compiled alongside of their literacy and numeracy data, will help the education systems get a clearer picture and compare the results from 2021 to previous years to get an understanding of where they would normally expect students to be at the end of Grade 6 versus the students who have in some cases missed significant amount of school,” Belisle tells SciDev.Net.

It’s estimated that the disruptions to education resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have set back progress in educational gains by 20 years.

To protect primary school children, UNESCO’s Global Education Coalition (GEC) has been assisting countries with tools to build their capacity in migrating from basic school learning to remote hybrid learning and train teachers in using online platforms. It is working with different partners in Africa and Latin America, in Asia with the Global Partnership for Education, and in the Caribbean with CARICOM to train teachers in developing open educational resources and remote learning modalities.

In the Pacific, GEC has worked in partnership with Moodle, an open-source online learning platform, together with other partners such as the Khan Academy to reinvigorate and develop further online platforms that pre-existed the COVID-19 crisis. It has also worked with Vodafone to offer “Zero Rating” access to digital data and resources in Samoa.

UNESCO has been providing policy support and advice to countries on how to open schools safely; prioritise teachers in the vaccination campaign; and organise remedial learning and ensure that the learning losses are compensated as soon as possible through different modalities.

The Framework for Reopening Schools provides practical and flexible advice for national and local governments and aid their efforts to return students to in-person learning.

However, with the more transmissible Delta variant of the novel coronavirus taking hold in the region and without adequate vaccines, school closures may continue in some countries such as the Philippines, which is one of the only two countries in the world yet to resume face to face classes since the lockdowns began in March 2020 according to UNICEF. The other is Venezuela.

How these erratic openings and closures, affecting the normality and the regularity of learning, will play out in the long term is anyone’s guess — there’s no precedent in the region.

*This article was edited on 13 October 2021 to reflect the correct organisation of Borhene Chakroun.

This piece was produced by SciDev.Net’s Asia & Pacific desk.