26/09/19

Fairer fish trade could fix nutrient deficiencies in coastal countries

By: Inga Vesper

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Local fish catch could help reduce nutrient deficiencies in developing countries — but only if more of it is distributed regionally, a study has found.

The study published on Wednesday (25 September) in Nature argues that developing countries are missing out on a crucial food source, because most of their fish catch is sold internationally. This deprives people within 100 kilometres of the coast, especially children, of important and easily accessible nutrients, researchers say.

“If these catches were more accessible locally they could have a huge impact on global food security and combat malnutrition-related disease in millions of people,” said lead author Christina Hicks, a professor at the Lancaster Environment Centre at Lancaster University, in northern England.

“These transformed diets suck fish towards the mouths of the better-off, meaning that not everyone who might benefit from consuming fish gets to eat it,”

Edward Allison, professor, School of Marine and Environmental Affairs, University of Washington

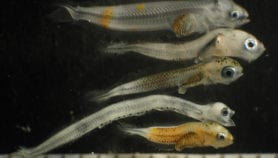

The international team studied 367 fish species in 43 countries, and noticed that levels of calcium, iron and zinc — which are crucial to healthy development — were particularly high in tropical fish species. Fish also contains omega-3 fatty acids, which help brain development and protect against heart disease.

A single portion of fish could provide half of a child’s recommended dose of iron and zinc, and nearly all the calcium it needs, the study showed.

However, more than half of the coastal countries studied showed moderate-to-severe nutrient deficiencies. This is because most fish caught in developing countries is either sent abroad directly or processed and sold to richer nations.

“In Mauritania, for example, around 90 per cent of fish caught in its waters is caught by foreign fishing vessels,” added Hicks. It does not even enter the local market.”

In Namibia, another example mentioned in the study, most of the fish is caught by local fleets, but then immediately exported, while 47 per cent of the country’s coastal population suffers from severe iron deficiency.

“Mauritania benefits from the licence fees, while Namibia benefits from the trade,” added Hicks.

Diverting a small percentage of a country’s fish catch into local communities would make a huge difference to nutrition, the study’s authors say. They found that trading just 9 per cent of the fish caught annually in Namibia locally would solve the country’s iron deficiency problems.

The situation is even more stark in Kiribati, where just 1 per cent of fish catch would address the calcium deficiencies affecting 82 per cent of people living in the Pacific island nation, according to the study.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), nearly half the global population — 3.1 billion people — derive at least 20 per cent of their protein from fish. Global fish consumption has grown from 9 kilograms per person in 1961 to 20 kilograms today, but a lot of this growth has taken place in the Global North.

Simon Funge-Smith, the FAO’s fisheries officer, recommends a policy focus to support inland fishing versus fish harvested from the oceans. He said: “Thirty per cent of all fish caught in Africa comes from inland fisheries. Almost none of the inland fish is traded internationally.”

But Edward Allison, a professor at the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington in the United States, points the finger at unsustainable fishing practices, which have brought prices down for rich nations with increasingly protein-rich diets.

“These transformed diets suck fish towards the mouths of the better-off, meaning that not everyone who might benefit from consuming fish gets to eat it,” he said.

In the study, Hicks and her colleagues propose several policy recommendations to address the skewed global availability of fish. These include supporting local, small-scale fisheries and reorienting the global fish trade towards better and more equal distribution of catches.

Xavier Basurto, an associate professor at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University in the United States, believes that the processing of highly nutritious fish into low-nutrient products for developed countries, including pet food, should also be curtailed.“For instance, one could regulate certain types of catch not to be used as fish meal for export because of its nutritional value for low-income populations,” he suggested.

But Hicks points out that there is little understanding of the processes at local level, saying that cultural boundaries, taboos and taste could also play a role in why these markets are undersupplied. Her team is planning to broaden its insights through several case studies.

“We want to go to key countries with high nutrient potential and really figure out what’s happening on the ground, and what can be done,” she added.