Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A research centre in Jordan aims to boost science and foster peace through international collaboration, reports Rehab Abd Almohsen.

Thirty-five kilometres northwest of the Jordanian capital of Amman, and less than 90 kilometres from the border with conflict-ridden Syria, a major research facility is slowly taking shape that could be a beacon of hope for a more harmonious future for the region.

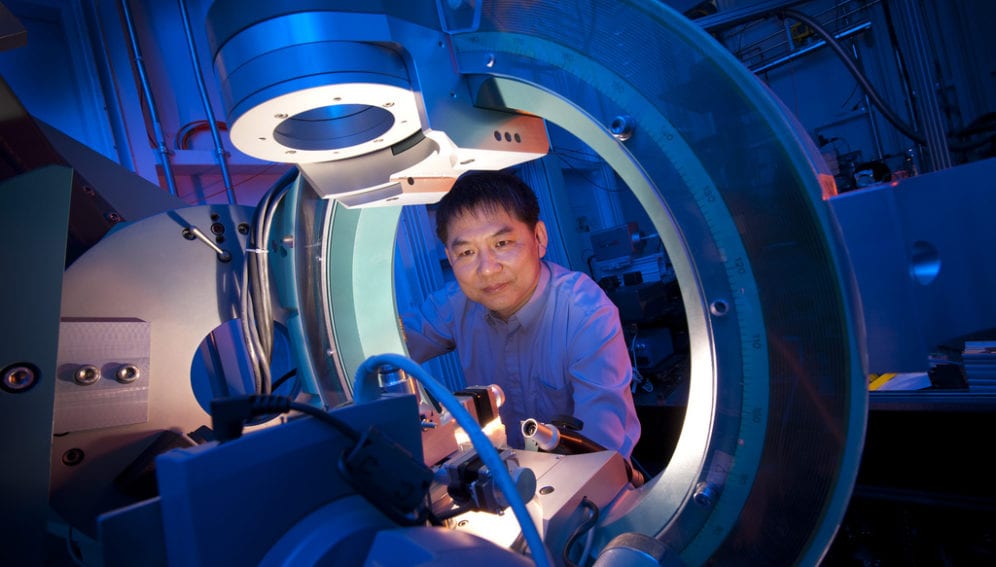

Known as SESAME (Synchrotron-Light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East), it will be the first major international research centre in the Middle East, bringing together scientists and governments from across the region.

The particle accelerator at the centre's heart started life in Germany, operating in Berlin between 1981 and 1999 under the name BESSY I.

When it became due for decommissioning, Herman Winick, a professor at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University in the United States, was among those who suggested that the components should be used to build a synchrotron light source in the Middle East.

Winick and others argued that the project could not only produce important science, but also help to improve relations between countries in the region by demonstrating what can be achieved through scientific collaboration.

With the support of UNESCO (the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and various Western and regional governments, the accelerator is now being rebuilt in Jordan, with experiments scheduled to begin in 2015.

But a significant funding gap still remains between what is required for full operation and what has so far been raised.

Powerful tool

Synchrotron light sources accelerate a beam of electrons to speeds close to the speed of light and send it around a circular tube, from which a number of 'beam lines' come off at a range of wavelengths.

As each beam line focuses light or another form of electromagnetic radiation on to a separate recording target, many experiments can be run simultaneously.

SESAME's users will be based in universities and research institutes in the region. They will visit the research centre to carry out experiments — often in collaboration with scientists from other centres or countries — and then take the data they obtain back to their own laboratories for analysis.

For example, Ibraheem Yousef, a SESAME beamline scientist from Jordan, plans to use SESAME to research ways of using infrared spectroscopy on living cells to diagnose cancer.

Yousef has already carried out research for a cosmetics company on France's national synchrotron facility, the Synchrotron SOLEIL, to test the effectiveness of shampoo and conditioner by using the facility's infrared beam to analyse the hair and skin structure before and after using the product.

Another SESAME beam line scientist is Messaoud Harfouche from Algeria, who is working on a research project with the International Atomic Energy Agency on heavy and toxic metals in the soil in the basin of the Jordan and Yarmouk rivers.

His research involves measuring toxic metals such as iron and chromium in the soil and then growing plants that can absorb them.

He depends on one widely-used application of synchrotrons — X-ray absorption spectroscopy — to help determine the soil's precise structure .

The technique can also be used in other scientific fields, including molecular chemistry, earth science and biomedical science.

Brain drain

One of SESAME's goals is to build up scientific and technological human capacity in the Middle East.

Harfouche points out that SESAME is already functioning as a training facility, even though it is not yet operating. "We have opened the door for hosting masters and PhD students, and already have a student from Al-Quds University in Palestine working on updating the beam lines and doing research on the design of storage rings, which collect beams of electrons emitted from the synchrotron".

However, the initiative is already facing a major challenge in combating brain drain. "The project gives researchers excellent training opportunities, but after this they often leave for a better offer somewhere else," says Mohamed Yasser Khalil, SESAME's administrative director.

Maher Attal, a Palestinian whose role is to set up the microtron that gives electron beams their initial acceleration, tells SciDev.Net that SESAME will offer scientists a valuable opportunity to carry out experiments within the region.

"The presence of this project will encourage universities to teach this branch of science and enhance regional research outputs in the region," he says. "It will enable us to keep up with the latest scientific progress in the field, unlike now."

Raising awareness

SESAME has four advisory committees, covering beam lines, scientific aspects, technical aspects and training. Each is comprised of senior scientists and accelerator experts from across the world and meets twice a year, with the role of committee members being to train and share their experiences with the project team.

Attal believes that SESAME will raise awareness of the importance of synchrotrons as experimental tools, encouraging more countries in the region to build their own synchrotrons and helping to reverse the brain drain.

"Iran and Turkey are each already planning to build a synchrotron and I hope that other countries in the region will do the same," he says.

But he adds that the synchrotron that forms SESAME — currently the region's only accelerator — is already 32 years old, having originally been completed in 1981. "The demands of users are more advanced than what the old machine can provide," says Attal.

To solve this problem, the scientists are trying to update some of the components. "For example, we have designed [an electron] storage ring and now we are inviting tenders for its construction," he says.

Science and diplomacy

Even though SESAME has yet to start work, it has already enabled Arab and Israeli scientists to work alongside each other, even at the planning stage.

Roy Beck-Barkai, principal investigator in the laboratory of experimental biophysics at Tel Aviv University in Israel, studies how biological materials interact to form complexes at the nanometre scale.

These interactions and the structures of the complexes are best seen using synchrotron X-ray scattering, such as that provided by SESAME, he says.

"Once operational, SESAME will be one of the international facilities that I will be travelling to, in order to measure these properties and to gain physical insights on biological and biophysical processes."

Israel has supported SESAME both financially and scientifically since the project started, despite the nation having a stake in several more-advanced synchrotrons in Europe, such as the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France, the Elettra synchrotron in Italy, and the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) near Geneva, Switzerland.

"Having a share in more facilities means more options for researchers like myself to conduct our science," says Beck-Barkai.

"And having SESAME just around the corner from our home laboratory in Israel is another good motivation, as it will allow us to transfer 'fresh' samples more easily [than to laboratories farther away], and will cut down on travel expenses."

Beck-Barkai is optimistic that the project will also provide an opportunity to overcome some of the hostility between the nations in the region.

"When we scientists meet and debate our science, everything else is put aside," he says. "I hope that the spirit of SESAME will resonate in our nations and governments, making them realise that we share the same passion [for research], and can work together for a better future for our region."

Funding shortfall

But the project faces major financial challenges as it seeks funding from governments in the region to cover both its construction and operational costs. A further US$35 million is required before it can start operating.

Khalil tells SciDev.Net that finding reliable funding is the biggest challenge at the moment.

The current members of the project are Bahrain, Cyprus, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority and Turkey. "Our job now is to convince new members to join," he says. "We are negotiating with Morocco, for example, to join and pay US$5 million membership."

SESAME will cost US$5.3 million a year to operate. "If the number of members does not increase, we will be in trouble," says Khalil.

And there are always background concerns about the potential impact of escalating conflict in the region.

"If the relations between Israel, Iran and the Arab countries deteriorate, the project will certainly face an unknown fate," says Attal.

Rehab Abd Almohsen currently holds an IDRC/SciDev.Net science journalism internship award.

This article has been produced by SciDev.Net's Middle East & North Africa desk.