Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

[SANTIAGO] The elimination of malaria has closely followed patterns of urban growth over the past century, raising hope that booming urbanisation in developing nations will lead to further reductions in cases of what is still one of the world's top killers, says a study.

The relationship between urbanisation and malaria's decline holds irrespective of countries' wealth, governance and latitude, according to the study, which says it is the first to reveal this pattern globally.

Yet the study could not say whether city growth causes the decline, and experts say that short-term measures targeting the mosquitoes that transmit the disease should be prioritised over any strategy of waiting for urbanisation to cut malaria rates.

Researchers from the United Kingdom and the United States used global data on city growth and malaria transmission maps to examine the relationships between the changes in these factors between 1900 and 2000.

They discovered that when 50 countries where malaria had existed in 1900 were finally certified as being malaria free, many more people were living in urban areas and the percentages of urbanised land were higher than is the case today in countries where malaria is still endemic.

Furthermore, the rate of urbanisation from 1900 was faster in those countries that had eliminated malaria than in those where it remains, the study found.

The close link also held for 29 countries that contained both areas declared malaria-free since 1900 and areas where malaria persists.

In three-quarters of these countries, mostly in Asia and the Americas, malaria-free areas were more urbanised and urbanisation had increased more rapidly than in areas that still had malaria.

The study also compared changes in malaria transmission in areas that are urban today versus those that have remained rural in 158 countries where malaria was endemic in 1900. It found that 82 per cent of countries saw malaria transmission fall by more in urban than rural areas since 1900.

The study says cities bring improved health, housing and wealth, all of which may cut malaria by contributing to changes in the behaviour of humans, mosquitoes and parasites.

But it failed to resolve a 'chicken-and-egg' question: does increased urbanisation cut transmission or does reduced malaria promote development?

"It's difficult to prove conclusively whether one is more of a driving factor than the other," Andrew Tatem, the study's lead author and a researcher at the University of Southampton, United Kingdom, tells SciDev.Net.

"We have strong evidence that urbanisation reduces malaria transmission and that reducing malaria promotes development, so the answer is probably that both factors [contribute]," he says.

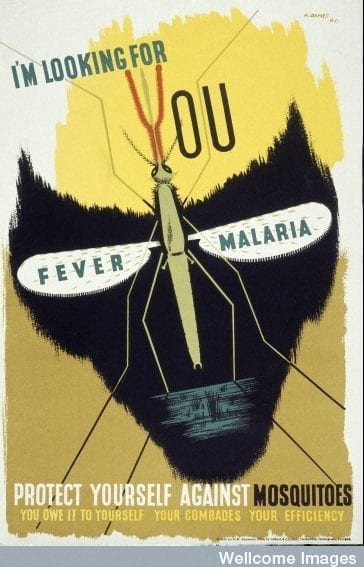

Justin Cohen, researcher at the Clinton Health Access Initiative, United States, says that measures such as using protective nets or spraying insecticides to kill mosquitoes can reduce malaria much faster than urbanisation.

"In many places, we don't have to wait for urbanisation to make our job a little easier: with sufficient investment, we can eliminate malaria today with our existing tools," he tells SciDev.Net.

The study was published in Malaria Journal last month (17 April).

References

Malaria Journal doi: 10.1186/1475–2875–12–133 (2013)