Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

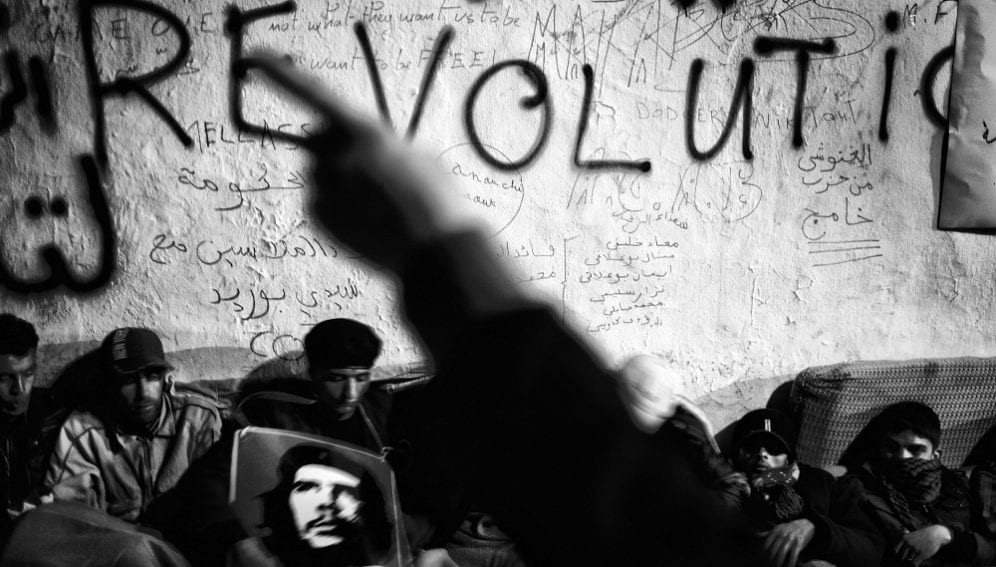

Science, technology and innovation (ST&I) had a key role in the discontent that led to the uprisings of the Arab Spring. But while information and communications technologies (ICTs) and social networks were important in mobilising people, they are insufficient by themselves to explain the uprising.

A knowledge economy framework gives a better insight — showing that it was disruptive innovation, a growing number of more educated and creative professionals, and better organised grassroots groups that led to the downfall of several Arab regimes in the region. [1]

The build-up of discontent

Sixty per cent of people in Arab countries are under the age of 30. Inequalities of access to knowledge have heightened frustrations among young people, particularly graduates and women. The discontent has historical roots, but was exacerbated by ill-conceived recent policies.

Historically, frustrations are due to the region — which spearheaded many advances in philosophy, mathematics, medicine, geography and literature about a millennium ago — now having a peripheral position in global science.

Arab countries have generally missed the industrial revolution because governments gave little importance to science and technology (S&T). In some countries, this was later exacerbated by colonial rules where the higher education system — for S&T in particular — was set up, in effect, for the exclusive benefit of the colonisers.

The education and training systems established since independence have resulted in different kinds of exclusions. For one, the public education system was often geared towards mass education, merely providing basic, general knowledge, unlike the high-quality private education available to those who could afford it.

There is also the issue of graduate unemployment — of S&T graduates especially — as poor qualifications fail to meet the demands of local industry. Similarly, technical and vocational education has been suffering from weaknesses such as low-quality teaching.

Finally, women, who have tended to outnumber men in tertiary education, found themselves with a dismal share of scientific and technical jobs due to discriminatiory policies and prejudices held about their capacity in ST&I. For example, Arab governments appoint few women as heads of research centres in spite of proven competencies.

Favouring foreigners

But the historical grievances go beyond higher education. Since the beginning of their industrialisation in the 1970s, countries in the region have relied excessively on ready-made technology from abroad. This has marginalised local expertise. As a result, design and engineering tasks that could have involved local faculty almost exclusively went to foreign consultancy firms.

More recently, people (especially the younger generation) have been brought up in a world of competition — and seeing their countries placed in the lower rankings on ST&I indicators has hurt their national pride. For example, Algeria coming last in The Global Innovation Index 2011 was generally perceived as a disaster and commented on publicly. [2]

In addition, the concentration of power in the hands of central government has prevented independent scientific research, hampering universities from taking the initiative, generating new creative ideas and innovating. Government policy also largely excluded many social groups that are part of civil society — young people, women and diaspora groups — from creative thinking and undertaking innovative projects.

The knowledge-economy approach

But moves towards the knowledge economy in recent years have brought changes across the Arab world. Such economies are based on harnessing knowledge for improved production processes that involve intensive use of ICTs, education that fosters more creative thinking, healthy institutions and a well-functioning system to promote innovation.

While commentators and the media have picked up on ICT and social media as key elements in the Arab Spring, they are by no means the only factors. The other components of the knowledge economy also played a significant role: innovation processes, education and governance.

The gradually improving education systems, mostly in ‘spring’ countries such as Tunisia, led to a growing level of critical thinking among the young generations. Young people have begun to observe the lack of accountability, helping to expose it in the media and public debate.

They have realised that ICTs offer a unique opportunity for creativity and disruptive innovation. This has been evident in neighbourhood groups organising logistics of protests, for example, or moving ahead with collective and democratic decision-making.

So, in essence, the actual organisation of the uprising was an outlet for young people’s innovative potential — because there was no outlet in the jobs market.

Leaderless movements voluntarily mobilised for a common cause and helped set up new governance principles within the protest groups: transparency, quick implementation of decisions, no hierarchy and the use of catchwords, such as degage (get out) in Tunisia. Degage went global, helping to mobilise people against the regime and eventually bringing down President Ben Ali in 2011.

Policy recommendations

Looking at the Arab Spring from this perspective, it may be tempting for the ruling elite to perceive the knowledge economy, and ST&I, as a threat. But it should be seen instead as a valuable opportunity to establish more inclusive, sustainable and diversified economies and egalitarian societies.

The ‘creative class’ of knowledge elites needs to benefit from a new, inclusive development strategy so they can become part of the evolving human capital of intelligence and creativity in Arab countries.

One way that governments can begin to build trust is by involving this class in major decisions that affect the economy and society. They can also reward knowledge and creativity both materially and symbolically, giving them free access to the media.

To promote economic growth and development, a new type of alliance is needed between political elites and the creative class in the region. The old alliances rested upon allegiance to the regime in power, alignment to the major political party and self-censorship. The new pact should be based on knowledge-based political and economic decision-making.

Integral to this is accepting science-based critical thinking as part of the new mode of governance — replacing a model that is based on military and autocratic rule with one based on accountability, ST&I, knowledge and meritocracy.

Abdelkader Djeflat is economics professor at Lille University, France, vice-president of the Globelics (The Global Network for the Economics of Learning, Innovation and Competence Building Systems) scientific board and coordinator of the Maghtech (Maghreb Technology) Network. He can be contacted at [email protected]

References

[2] The Global Innovation Index 2011 (INSEAD, 2011)