By: Barbara Axt

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A global initiative launched last week aims to reduce the environmental impact of the invasive marine species being spread across the oceans by ships.

The GloFouling Partnerships project, led by the UN, will support countries around the globe in using innovations to combat biofouling, the build up of marine animals such as barnacles on underwater surfaces, and in implementing guidelines on this topic from the UN’s International Maritime Organization.

Shipping authorities in participating countries will receive support in using technology to limit the number of species that attach themselves to ships or travel in their internal tanks, including methods such as coating hulls in special paint and monitoring the spillage of ballast water near coastal areas.

The twelve countries leading the initiative are Brazil, Ecuador, Fiji, Indonesia, Jordan, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Tonga.

Removing or curbing the spread of the organisms could also improve the efficiency of shipping, a huge source of carbon dioxide emissions. “Biofoul on the hull of a ship can slow it down and increase energy consumption by 12 per cent,” says John Alonso, assistant technical adviser at GloFouling. “It also can reduce the productivity of tidal energy engines. It can increase the weight of nets in aquaculture, and even harbour parasites that affect the fish.”

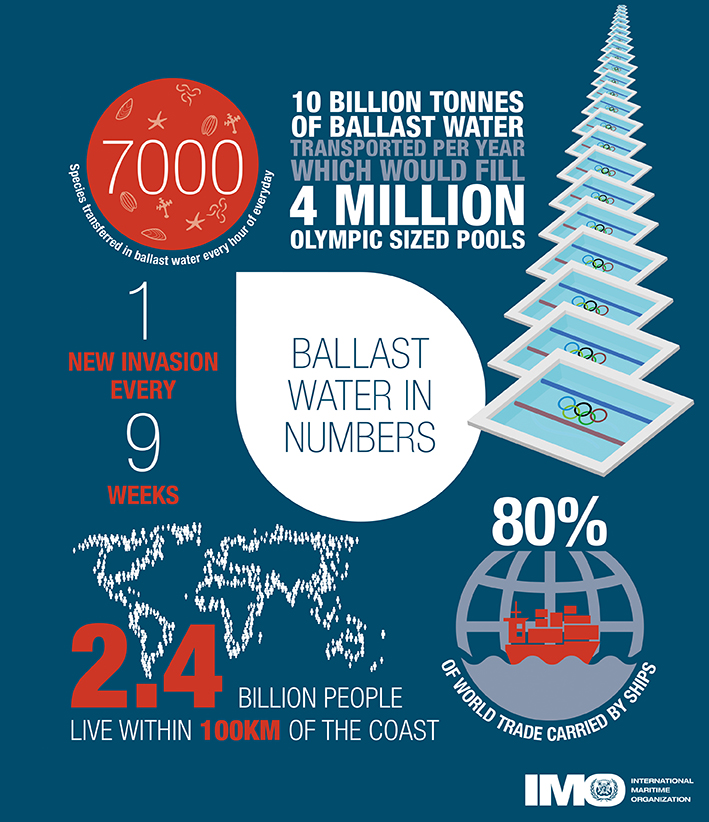

Invasive species are animals that have been transferred from their natural ecosystem to new ones, where they spread rapidly and cause harm. They reduce biodiversity by altering habitats and changing predator-prey relationships. According to Alonso, around half of all marine invasive species are transported on the hulls of ships, while another 30 per cent are introduced through ships releasing water from their hulls.

This ballast water is a particular concern. It is used in special tanks in cargo ships to improve stability when a ship is not fully loaded. It carries bacteria and other microorganisms, as well as eggs and larvae, which are released along with the water when it is pumped back into the ocean.

It is difficult to regulate the discharge of ballast water, especially in countries with limited technical capacity. The GloFouling initiative has received US$6.9 million to remedy this by providing development of, and access to, technological tools.

“We will work on capacity building by using training tools, providing information, creating conditions for technology transfer, and also educating decision-makers,” says Alonso. “In the future, the [participating] countries will reach the other countries in the region.”Fisheries are an important industry for many developing countries. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, around 10 per cent of the global population rely on fishing for their livelihood. Many small island states make more than half of their GDP (gross domestic product) from fishing, but are also often based along heavily used shipping routes.

According to research, more than 80 per cent of marine protected areas suffer from invasive species, potentially causing billions of dollars of damage to local fishing industries.

Oceanographer Fred Dobbs at Old Dominion University in Virginia, United States, welcomes the fact that developing nations are taking centre stage in the project. “I think it's a very smart step forward by the IMO,” he says. “After the good results of the GloBallast initiative, which led to the Ballast Water Convention signed last year, they are moving on to biofouling, repeating the successful strategy of working with developing countries.”