Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

A UK start-up says it has developed a low-cost, ecological alternative to traditional shrimp farming by using bacteria as both a water filter and food for its shrimp.

IKEA-like portable units using microbes and solar power to cheaply grow shrimp indoors could transform the booming aquaculture sector and prevent further environmental degradation, according to its inventors.

If made available to farmers in developing countries, the technology could help tackle malnourishment while reducing environmental degradation, and all at a lower cost than current shrimp production, they say.

Founded by biochemical engineering students from University College London, the start-up Marizca is producing whiteleg shrimp in central London in its first trial operations.

Global production of farmed shrimp has been growing at about ten per cent a year, according to conservation charity the World Wildlife Fund, and farmed shrimp now accounts for about 55 per cent of global shrimp production.

“The bacteria eat the shrimp waste and the shrimp eat the bacteria when they have reached a certain size. It makes producing shrimp a lot cheaper.”

Leonardo Rios

But the industry has been criticised over the past decade for environmentally damaging practices, that that lead to the destruction of mangrove forests and pollution caused by effluent from shrimp ponds.

Marizca co-founder Leonardo Rios says the firm's indoor units will avoid the problems caused by creating outdoor shrimp farms in fragile environments.

While such indoor facilities are normally expensive to run, Rios says the use of water-purifying bacteria in their units means less water and energy is needed. Also, the microorganisms meet up to 30 per cent of the shrimp's food needs.

"The bacteria eat the shrimp waste and, at the same time, the shrimp eat the bacteria when they have reached a certain size," he says. "It makes producing shrimp a lot cheaper."

Using microorganisms in aquaculture — a technology called biofloc — is not new.

Several such operations exist worldwide, but so far they have had limited reach, according to Michael Phillips, a researcher at WorldFish, a non-profit aquaculture research centre.

"Biofloc is not yet widely applied because the technology is not yet perfected or even widely available," he says.

What is new about Marizca's biofloc technology is the use of a "unique" starch source, according to Rios. He says the starch helps create prolific microorganism growth.

Current interest in biofloc stems from a research drive to find an alternative food source for farmed shrimp. According to Phillips, most shrimp farms rely on industrial feed made partly from fishmeal, a practice that many see as unsustainable.

"A criticism of the industry has been that you are feeding aquatic animals to grow another aquatic animal and that it's not an efficient way of producing shrimp or fish for human food," he says.

Globally, shrimp farms account for more than a quarter of fishmeal consumption, according to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization.

Rios believes his units, which are designed "like IKEA furniture", could benefit food-insecure regions.

"Our units are easy to transport, to automate and use, and consume very few external materials," says Rios. "They use so little energy that potentially they could be solar-powered, so we believe that working with the right NGO, we could really help tackle malnourishment."

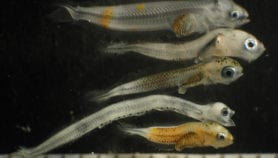

With Marizca's system, the shrimp are grown in layered trays with about 300 animals per square metre. One unit can produce roughly 10,000 shrimp every three months — fairly standard figures for an intensive shrimp operation, but with much lower operational costs, according to Rios.

Nonetheless, the technology's broader relevance to small-scale shrimp farmers, who constitute the majority of the industry in many developing countries, is not guaranteed.

Phillips questions whether a closed, indoor system would really require less energy than the open-air ponds in which shrimp are usually farmed in developing countries.

"I would imagine that the energy required for production would be more substantial [in these units] than in less-intensive ponds found in warmer tropical regions," he says.

But he adds that biofloc technology could help shrimp farmers globally if it were widely adopted.

Pending licensing, and with funding from UK investment firm Student Upstarts, Rios says the first batch of Marizca's London-produced shrimp will be on sale within the year.