By: Anne Moorhead

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

The University of the South Pacific’s massive catchment may mean less research cash, but its science helps the region, reports Anne Moorhead.

[SUVA, FIJI] The University of the South Pacific, known locally as USP, is one of just two regional universities in the world: the other is the University of the West Indies.

Serving the academic and research needs of 12 small island countries spread over a great expanse of ocean brings obvious challenges, and the university does not currently fare well in international rankings such as those produced by Times Higher Education and QS (Quacquarelli Symonds). But this regionally well-respected institution may have lessons to teach the rest of the world about engagement and impact beyond the campus gates.

SPEED READ

- Cost of educating students over vast area limits money available for research

- But university’s work has fed into fisheries management and policies across the region

- Drive to develop new drugs by tapping into vast marine resource

The university was established in Fiji in 1968, when the nation was a British colony. Its courses and degrees are recognised internationally and are claimed to be on a par with those from Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

The university’s main campus is still in Fiji, with sizeable campuses also in Samoa, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, and smaller ones in each of the other member countries: the Cook Islands, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Tokelau, Tonga and Tuvalu

Given that the 12 countries comprise around 600 inhabited islands dispersed over more than 30 million square kilometres of ocean and several different time zones, distance learning and flexible learning are given high priority. Of the approximately 20,000 students, about half study by this method.

Nonetheless, the costs of being the main tertiary education provider over this vast region are inevitably high.

This, says John Bythell, USP’s pro vice-chancellor for research, has implications for the research agenda.

"Compared with other universities, we need more teaching staff to reach all our students. This leaves us with fewer resources for research and fewer research staff," he explains. Because one usual measure of a university’s success is quantity of research outputs, this leaves USP at a disadvantage. "But if you look at outputs on a per-researcher basis, we’re actually doing quite well — probably as well as a low- to mid-ranking Australian university," he says.

Local research impacts

Bythell, who came to USP from Newcastle University in the United Kingdom last year, aims to raise both the quantity and quality of USP’s research output, and so boost its international ranking. But he stresses that, on another measure of success, USP’s research already excels.

"Our strength is in research impact, at both practice and policy level," he explains. "Unfortunately, such impact is hard to measure, so it’s given less weighting in ranking processes, but I don’t think it’s too controversial to say it’s what matters most."

USP’s Institute of Applied Sciences (IAS) is where much of the engagement that leads to these impacts takes place. Describing itself as the interface between the university’s expertise and facilities and the governments, businesses and people of the Pacific islands, the institute focuses on five areas: food, environment, water quality, marine natural products and community-based resource management. It also manages the South Pacific Regional Herbarium.

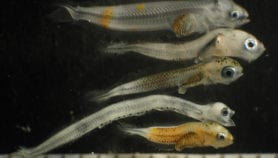

IAS’s LMMA ran a campaign to protect fish spawning grounds.

Credit: Flickr/ Saspotato

One of its proudest achievements is the Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMA) initiative, which IAS helped create more than ten years ago. Now a network of more than 600 locally run near-shore sites in several Pacific island countries, the project is helping to push the boundaries of science-informed community-based resource management.

"We have several Fijian postgrad students working in the LMMAs here in Fiji," says IAS director William Aalbersberg. "The research they are doing is based on questions asked by the communities, so it responds to real needs."

Current research includes looking at how LMMAs affect surrounding areas; examining interactions between herbivorous fish, algae and coral to investigate whether the higher numbers of fish in the protected areas ultimately leads to more live coral; and methods for scaling up and networking LMMAs.

Taking lessons on board

Communities, nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), the private sector, governments and researchers are all involved in developing LMMAs. This helps to ensure that successful research is readily absorbed into practice at the relevant level. Targeted awareness-raising activities include the usual posters, training guides and community workshops, but are sometimes more creative: a campaign to protect the spawning grounds of a Fijian fish was launched by a ‘flash mob’ at an annual festival in August. [1]

The LMMA project and related work have also had a direct impact on fisheries and coastal management policy in Fiji.

IAS staff helped draft fisheries legislation that recognises ‘customary fisheries management and development plans’ such as those on which LMMAs are based, paving the way for legal protection of the LMMAs. In addition, a framework for a national integrated coastal management plan was recently drawn up by an IAS staff member, at the government’s request.

These examples illustrate one advantage of working in smaller nations.

"Unlike larger countries, here we have much closer links with high-level decision-makers," explains Bythell. "We know many of them personally. In fact, many of them are USP alumni. So linking research and policy in this part of the world is a more direct process based on individual contacts."

Aalbersberg agrees. "The IAS trained many of the people who now hold senior environmental jobs in government and conservation NGOs in the region. For example, we developed a course in the 1990s because a lack of local skills became evident when countries were developing national biodiversity action plans. So we have built and maintained links over the years that are extremely fruitful."

Drug discovery

Another research area in which USP is gaining an international reputation, and aiming for impact far beyond the region, is drug discovery.

"Our comparative advantage is being in the middle of the largest untapped natural resource in the world," says Aalbersberg.

Katy Soapi is researching marine organisms for their antimalarial and anticancer properties.

Credit: Joel Adriano

"We’re building a world-class team of researchers to make the most of that advantage." The staff of the Centre for Drug Discovery and Conservation, housed within the IAS, includes a former head of drug discovery at pharmaceutical firm SmithKline Beecham.

"Many marine organisms aren’t able to move and can’t escape predators, so to protect themselves they produce strong defence chemicals. These are what we are interested in," explains chemist Katy Soapi.

A Solomon Islander, Soapi led a bioprospecting expedition to her home country earlier this year. Indications are that the seas off the Solomon Islands may be a particularly rich source of useful chemicals: two antimalarial compounds, an anti-inflammatory compound and two cytotoxic compounds, which have potential to treat cancer, have been discovered there in the past four years.

The 117 samples collected by Soapi’s expedition, including those from sponges, sea squirts and algae, are being assessed for antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial and anticancer properties.

New strategy

The university enters a new phase this year, with the launch of a strategic plan that aims to strengthen research, especially in those areas where USP has an advantage, such as marine sciences.

Six multidisciplinary research clusters have been built around key issues for the region, such as climate change, human security and Pacific Ocean and fisheries management. Climate change is also the main focus of USP centre of excellence the Pacific Centre for Environment and Sustainable Development.

"We may face some unusual challenges at USP, but we are also committed to making the most of our unique opportunities," says Bythell. "We have some interesting and exciting years ahead."

References

[1] Nakeke, A. More eggs…more fish (Fiji Times, 2012)