16/08/21

Feeding the future: facts and figures

By: Gareth Willmer

Send to a friend

The details you provide on this page will not be used to send unsolicited email, and will not be sold to a 3rd party. See privacy policy.

Even before COVID-19 unleashed itself on the globe, the world had swerved off course to meet its target of zero hunger by 2030. Hunger is increasing, while nutritious food remains out of reach for many of the world’s poorest.

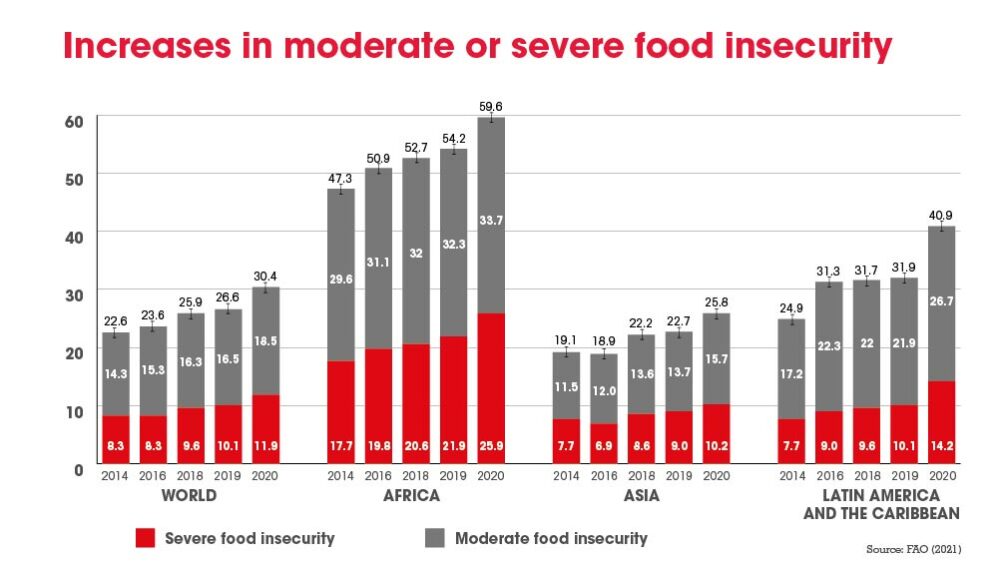

Figures from a multi-agency UN report show that global food insecurity rose as much last year as in the previous five years combined. The number of undernourished people increased by as many as 161 million, reaching up to 811 million – or around ten per cent of the world’s population. The most pronounced rise was in Africa, where one fifth of the population is undernourished.

The UN report also estimated that – under the current trajectory – the world will fall nearly 660 million people short of the SDG 2 objective of ending hunger for all by 2030. That includes a deficit of 30 million due to COVID-19’s lasting effects.

Other studies have highlighted how rapidly global lockdowns exacerbated hunger issues in individual countries. As early as April 2020 – the month after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic – nearly half of rural households in Kenya and 90 per cent in Sierra Leone faced missed meals or reduced portion sizes, according to one estimate.

Many lower-income countries increasingly face a so-called ‘double burden’ of malnutrition, whereby undernutrition and obesity coexist. In a 2019 report, this was estimated to be experienced by more than a third of low and middle-income countries. Nutrition specialists increasingly refer to a malnutrition ‘triple burden’, which recognises micronutrient deficiencies .

Vulnerabilities

The pandemic has served to expose the vulnerabilities in food systems which are rooted in conflict, climate extremes and economic slowdowns. Coming on top of these factors, COVID-19 has contributed to “one of the largest increases in world hunger in decades”, says the UN report.

Given that the outlook for malnourishment was already “alarming”, as underlined in the same UN report for the previous year, food remains unaffordable and inaccessible for many. Yet, at the same time, the world already produces enough to feed everyone on the planet.

Apart from health complications, malnutrition causes severe economic impacts through reduced productivity, estimated by one study at up to US$850 billion annually among businesses in developing countries.

Additionally, food access is a gendered issue, with women farmers often especially at risk of hunger in crises due to discrimination and limited access to resources. Yet women play a pivotal role in food security – comprising almost half the agricultural workforce in developing countries, while more than 60 per cent of employed women in Sub-Saharan Africa work in the sector.

That problem has been highlighted during the pandemic, with the food insecurity gap between men and women widening from six to ten per cent in 2020, according to the UN.

Loss and waste

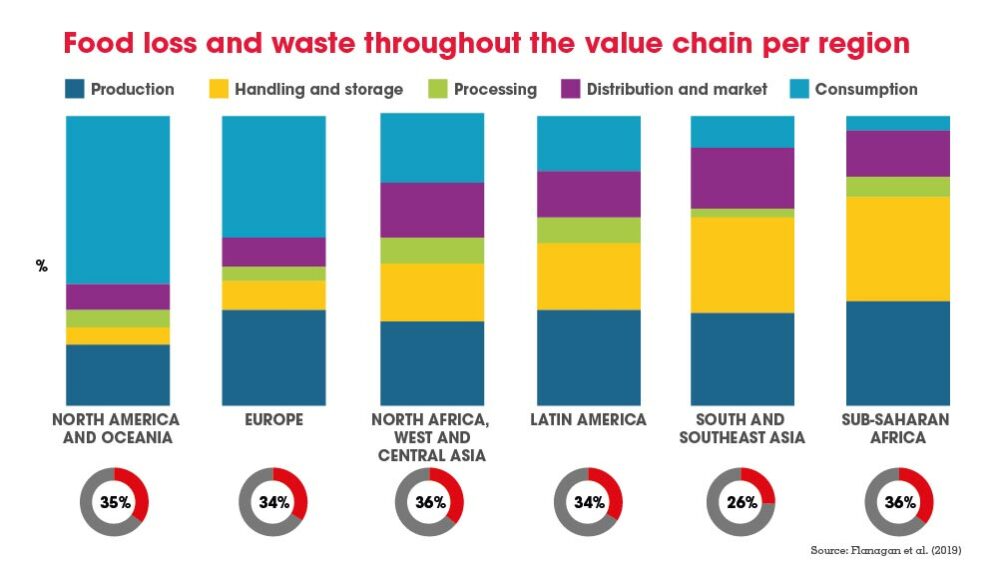

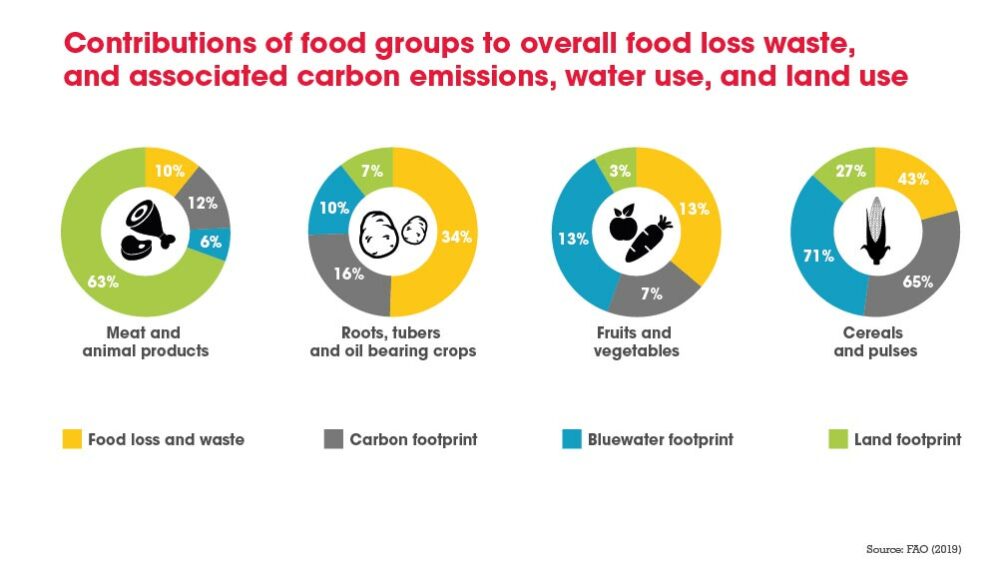

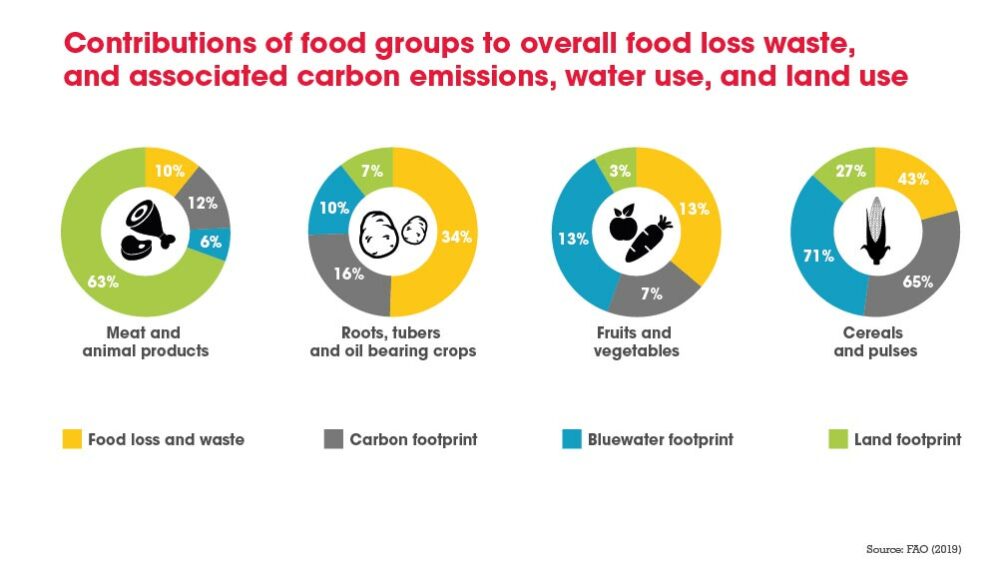

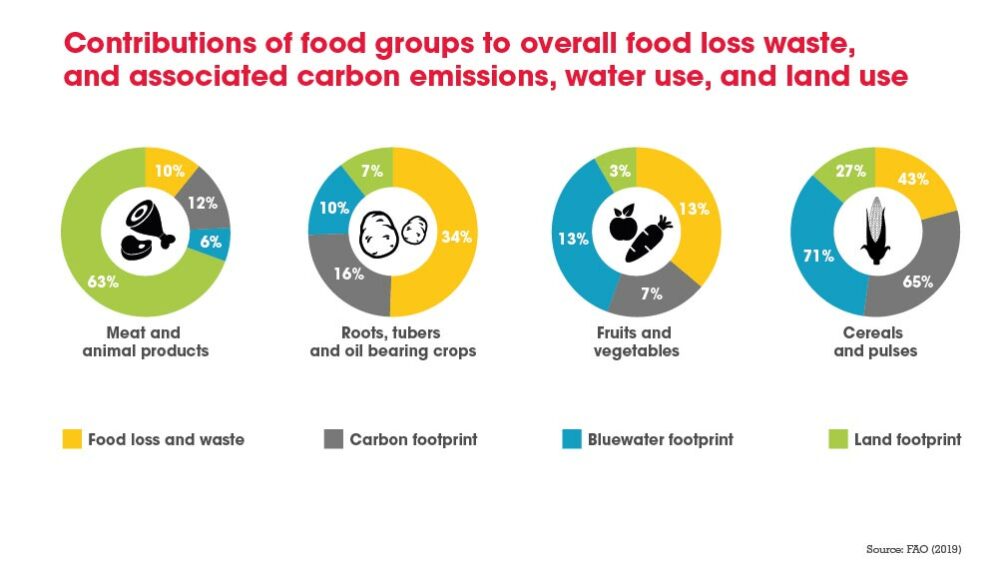

Drastically cutting food loss and waste could improve food security for millions around the world. The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that 17 per cent of global food production is wasted, equating to almost 1 billion tonnes in 2019.

Earlier estimates cited by the World Bank indicated that around one third of global food supply is lost or wasted. COVID-19 further disrupted supply chains and led to some farmers destroying unsold crops.

Progress towards halving per-capita food waste by 2030 has been “patchy at best”, added the World Bank.

Solutions are impeded by a lack of data, particularly from developing countries. “Few governments have robust data on food waste to make the case to act and prioritise their efforts,” says UNEP, while the World Bank refers to a “surprising” lack of studies that seek to link changes in loss and waste with effects on how food systems operate.

This waste is significant from an environmental perspective too, accounting for up to ten per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to UNEP. The size of this impact is underlined by the commonly cited statistic that if food loss and waste were a country, it would be the nation with the third-largest volume of greenhouse gas emissions.

Environment and biodiversity

Improvements in agricultural productivity need to be balanced against the critical need to minimise environmental deterioration.

Recent research has cited food production as the main culprit for biodiversity loss over the past half-century, being identified as a threat to 24,000 of the 28,000 species thought of as at risk of extinction. Agriculture also takes up half of the world’s habitable land, with the global food system estimated to account for about a third of human-made carbon emissions.

Furthermore, rainforest covering the equivalent of 1.5 times the area of Spain was cleared in the Amazon between 1978 and 2020, around three-quarters of which was to make way for cattle ranching. In 2019, primary forest the size of a football pitch was lost every six seconds in the tropics, according to data from the University of Maryland. And more than a quarter of forest loss globally from 2001 to 2015 resulted from rising production of commodities such as beef, soy – most of which is grown to feed livestock – and palm oil.

The growing prevalence of monoculture – the planting of single crops over wide areas – also threatens biodiversity and raises vulnerability to pests, pathogens and disease. This is a concern in locations such as Asia and Latin America, where large industrial farms have been growing single crops across thousands of hectares of land.

“In many parts of the world, biodiverse agricultural landscapes in which cultivated land is interspersed with uncultivated areas such as woodlands, pastures and wetlands have been, or are being, replaced by large areas of monoculture, farmed using large quantities of external inputs such as pesticides, mineral fertilisers and fossil fuels,” said the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in a 2019 report.

Maintaining crop diversity can help build long-term resilience in food systems – providing substitutes when others fail or fall victim to disease and pests. But just nine plant species of the more than 6,000 that have been cultivated for food make up two-thirds of global food production, according to the FAO.

Push for change

Despite the multiple, sizeable problems faced within food systems globally, international efforts will address these issues this year, including the global climate change talks, COP26, and the UN’s Nutrition for Growth Summit.

Key among these is the UN Food Systems Summit in New York this September. However, this event has been mired in controversy: small-scale farmers, indigenous and civil society groups boycotted a pre-summit in July, while scientists boycotted or withdrew from proceedings amid concerns that the meeting favoured big high-tech agribusiness.

Meanwhile, public health, nutrition and environment specialists have been working towards defining what constitutes a nutritious diet in a bid to help countries develop frameworks for sustainable diets. One of these is a guidance tool that has been applied in regions including Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America.

Another is a reference diet by the EAT-Lancet Commission that sets out a daily recommended diet, in which items can be swapped depending on culture and preferences. It estimates that adopting this could avoid more than 11 million deaths per year by 2030.

However, affordability remains a key hurdle, with a study indicating that many of the world’s poor would currently have to spend more than their total per-capita household income to afford such healthy diets.

The UN report also estimates that a healthy diet is unaffordable for a staggering figure of more than three billion people worldwide. With the world population continuing to expand, sustainable, healthy and affordable food solutions are needed to turn the tide and end global hunger. This year’s events will hopefully at least put these issues firmly at the top of the global agenda.